Family Souvenirs – Poland – Recollection of “My Pre-War Schools”

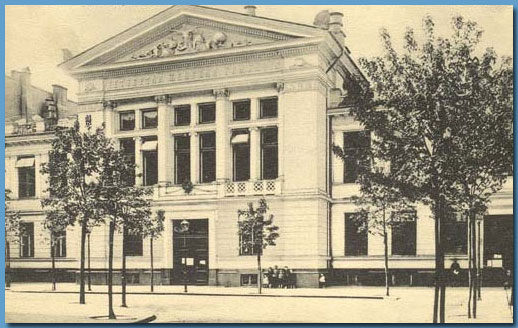

School of Nicholas Rey

I started learning in a real school from the 5th grade of primary school (now primary school). I studied the first four classes at home with my parents and teachers. At the end of the 1932/33 school year, I passed a “serious” exam in the field of 4 years of elementary school and from September I started normal education in the fifth grade in the elementary school at the gymnasium and high school. Mikołaj Rey, in Warsaw at Małachowski Square. It was a school run by the community of the Augsburg Evangelical Church and was considered one of the best schools for men in Warsaw. She was famous for a very good team of teachers and a nice atmosphere.

men in Warsaw. She was famous for a very good team of teachers and a nice atmosphere. Contrary to appearances, her students are not only sons of Evangelical families. Children from the so-called good families, but the social cross-section was quite wide. In our class – and it was probably a typical class in this respect – most of the students were Catholics. So we stayed in class for religion lessons; quite a large group of Evangelicals moved to another class. The Orthodox (there was one in our class) and Jews (three) – as far as I remember – had religion lessons outside of school.

From the teachers I remember Koelichen’s tutor, the Polish language teacher – prof. Klos (he later became an academic teacher at the University of Warsaw), biology – Szaniawski, mathematics – Jakobi and PE – Lokajski, a famous athlete, Olympian (he died in the Warsaw Uprising).

Of my colleagues, my friends are most of all remembered by my friends: Stefan Szeffel (lost his leg in the Uprising, after the war he died hunting due to an explosion of a grenade found by a boy from a campaign), Olgierd Wilczewski (shot during the occupation), Staszek Kłopotowski (died in a concentration camp ), Wojtek Brzozowski from a parallel class (in an interview with the Home Army, he lost his leg in the Uprising, after the war he was a researcher at the Gdańsk University of Technology and then a professor at the Nuclear Institute in Świerk, he died a few years ago); as well as – in the parallel class – Stanisław Gebethner – from the parallel class (now a retired professor of the University of Warsaw), Tadeusz Brygiewicz, Roman Kulczycki, Andrzej Urbański, Russian Borodin (he drew excellent caricatures with a pen) and the German Horst Ludwig (reportedly killed as a Wehrmacht officer).

I remember this school with pleasure. There was a good atmosphere of camaraderie and friendship in her. I didn’t have any problems with my studies. So it was pretty good.

The history that I know in detail can testify to the relations prevailing in this school. The son of the Minister of War, Kasprzycki, attended a parallel class. Kasprzycki lived near Warsaw, probably in Konstancin, and his son was brought and taken to school by a driver or minister’s adjutant.

At that time, the so-called “Choo-choo”; it took about an hour to travel to Warsaw. Its final stop was at Belwederska Street, more or less where the Russian embassy is located today. The journey from there to the school on Małachowski Square was quite a long – for those times – piece of the road. No wonder that young Kasprzycki was picked up and driven away from school by car.

Before the war, a passenger car was a luxury facility in Poland and none of the other students came to school by car, despite the fact that in the whole school (primary school, middle school and high school) at least a dozen students were sons of very wealthy Warsaw families.

The head teacher saw fit to ask the minister for an interview. The minister accepted the invitation. Both gentlemen stated that commuting from Konstancin by train does not make sense, but in order not to violate the school’s customs, the son will be taken by car to the Ministry of Military Affairs, and from there – to the school by public transport. It should be emphasized that this agreement was kept.

It was said at school that similar conversations had previously taken place, and with similar success, between the principal and a few other dads.

Rey’s school, like most Warsaw schools, had its own school estate – Rejówka in Kąty near Piaseczno. We went there twice a year for the whole week. For four days before noon there were 4 hours of lessons – a different subject every day; on other days (Saturday was a working day) and in the afternoon – sports activities, games and fun.

On the first floor, there were two or three bedrooms for students and teachers’ rooms. There was a dining room downstairs, a school classroom and a large common room. There is a kitchen and a workshop in the basement.

I remember the sentence of Mr. Mikołaj Rey himself burned on a plank hanging next to the fireplace: “Who is cold very much when the chimney is on fire”, as well as a drawing of two donkey heads with a tiny caption “and now there are three of us”. Everyone who came to Rejówka for the first time was obligatorily asked to read this inscription. Some, however, were prejudiced by their older colleagues and read “and now there are three of you” to the scandal of those around you.

In winter, novices were tricked into an extraordinary legume served exclusively for them. The old regulars told miracles about this extraordinary delicacy, and the more greedy could not wait for it. The disappointment came when it turned out that it was pure, fluffy snow covered with cherry or raspberry juice.

I have been to Rejówka 8 times in total. I was always looking forward to the trip, just like almost all my colleagues, and I came back with nice memories, and most of all refreshed, despite quite intense physical activities. School activities, most often used to revise more difficult parts of the material, also gave very good results. Four consecutive lesson hours, devoted to synthetic discussion of selected topics from one subject, organized the messages well and favored their consolidation. This time was also devoted to catching up due to reasons beyond the school’s control (e.g. a break in lessons caused by very strong frosts).

I was in Rejówka for the last time in the late spring of 1937, without foreseeing that this stay would have such serious consequences for me.

It was in early June. I remember that the weather was beautiful and sunny. We went in the early afternoon with our teacher and PE instructor to visit the ruins of the castle in Czersk. We went to Góra Kalwaria by cable car, we went to the castle in Czersk on foot. A pleasant walk: 3-4 kilometers on a warm spring day.

We were to walk all the way back, about 15 kilometers, as part of the “night march”. In Góra Kalwaria, a horse-drawn cart from Rejówka was supposed to wait for us, which came there to collect a few bags of cement needed for some minor renovation. He was also supposed to give a lift to any marauders for whom the described escapade would turn out to be overwhelming.

We were returning from Czersk around six in the afternoon, maybe a bit later. The weather started to deteriorate and we were caught by a short but very violent storm. We waited it in Czersk, in the barns of the hospitable hosts (they offered us delicious fruit) and, already very tired, we reached Góra Kalwaria, when it was already completely dark.

I don’t know why, despite being exhausted, some of us fell into the so-called “Calf delight”. It happens at fourteen.

It was dark in the town, the streets were empty, and in the gutters there were huge puddles after the evening downpour. A cement wagon was driving next to us. We came to the conclusion that we absolutely must make a good joke. Someone noticed that one of the bags was cracked, and some cement had spilled out from under the tarpaulin covering it. Someone mixed the cement with the water from the pool; Finally, someone had a “genius” idea to use it to cover the key holes in the padlocks that locked the shops on the main street. It was dark in the street, the cart was behind marching schoolboys, and no one paid any attention to the three or four marauders following the cart on both sides of the street, and very conscientiously fixing a few padlocks with cement.

It is worth mentioning here that before the war, a rabbi famous in Poland (and apparently not only in Poland) resided in Góra Kalwaria and almost all the shops were owned by Jews. We were not interested in the nationality of the owners at all. We haven’t thought about it. I think that the course of events would be the same if they were, for example, Chinese or highlander stores.

On the second day a few shops on the main street in the morning were not opened. The padlocks had to be sawn. Nobody thought that it was a feat of frisky students from the 2nd grade of junior high school.

Dość długo udało się zachować tajemnicę i chyba nigdy oficjalnie nie została ona ujawniona. Po prostu kilku uczniów, a wśród nich i ja, od nowego roku szkolnego przeniosło się do innych szkół. Cicho, spokojnie, bez rozgłosu i oficjalnie z różnych przyczyn rodzinnych. Rozmowy z rodzicami odbyły się dyskretnie. Ja miałem zostać przeniesiony do gimnazjum państwowego im. Tadeusza Czackiego, które mieściło się o parę kroków od naszego domu, na końcu ulicy Kapucyńskiej. Były jednak jakieś trudności formalne i nie udało się załatwić przeniesienia w ciągu dwóch czy trzech tygodni, jakie zostały do wakacji.

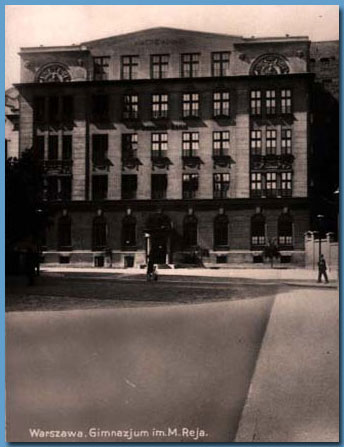

Junior high school Gen. Sowiński

I started the new school year 1937/38 in the 1st municipal junior high school. Gen. Sowiński in Wola. I had to be admitted there, because my father was formally a municipal worker, he worked in the hospital. Baby Jesus. I only attended there for 3 months. In December, I was already a student of the Czacki gymnasium.

Wspomnień z gimnazjum miejskiego nie mam praktycznie żadnych. Byłem tam tak krótko, że zanim zdążyłem się zaaklimatyzować, już mnie tam nie było. Pamiętam tylko, że po gimnazjum Reja, pierwszy kontakt z nową szkoła, to był dla mnie prawdziwy szok. Nie dlatego, że zmienili się koledzy ze środowiska zamożnego (na ogół) mieszczaństwa na środowisko robotnicze i drobnych urzędników, ale z powodu całkowicie odmiennego podejścia nauczycieli. U Reja szanowano i rozwijano indywidualność ucznia. Tu znalazłem się w wielkiej fabryce, której zadaniem była masowa edukacja.

I didn’t have time to make friends with anyone, I don’t remember any of the teachers, except the French teacher. Very few students of this school studied French. Therefore, despite the merger of the “French” from two or even three parallel classes, there was a small group of us.

I knew French fluently from home (it was worse with spelling). I was fluent in a literary language, not a school-reading language, I had a good accent and a lot of words. Very soon I realized that our brave teacher knows the rules of grammar, recites all exceptions to these rules fluently, but speaks unusual and with a bad accent. After some time, having gained confidence, I began to invent my own phrases and explain that in Paris, on the “rive gauche” (left bank of the Seine), this is what they say.

Unfortunately, no one could appreciate it, because my colleagues usually did not understand what was discussed, and the more urgent approached me during the break to write down new phrases! I couldn’t refuse them or admit to the whole hype, because I didn’t know them enough and I didn’t know how they would react to it.

Junior high school Tadeusz Czacki

In December 1937, just before Christmas, I entered the Czacki gymnasium. Now I walked to school in 5 minutes, and by running it was possible to reach it in 2 minutes. It was a great relief after the troublesome tram journey to Wola. Today, the distance from Miodowa Street to Młynarska Street seems small. It was a whole trip then; you traveled, crowded with trams through narrow streets, “endlessly”.

At Czacki’s I breathed a sigh of relief. There was a completely different atmosphere there, much closer to the Rej school. I acclimatized very quickly and made friends. Most of the colleagues were the sons of clerks and craftsmen, as well as workers. For example, my class was attended by Jurek Soiński (he was arrested at the beginning of the occupation when he tried to cross the green border to Hungary, he died in Oświęcim), the son of a senior foreman from an arms factory in Fort Bema, with whom I made friends very quickly. We were often at home.

Our class tutor was the Latin professor. Lechicki, a nice fat man, dragging from Lviv, nicknamed Watermelon. We liked him, and also his constant saying: “The whole class walks around the class and does not pay attention to my remarks, and if I call my parents, no consideration will be taken into account.” He said it in such a funny way that we often fidgeted in his class just to get him – supposedly upset – to say his phrase; after which it got absolutely silent. Good-natured Watermelon pretended to be so terribly upset that he couldn’t form a sentence correctly, and we pretended that we could barely breathe after such a terrible threat.

Professor Sobolewska lectured on mathematics. I have never had any problems with this subject, and it so happened that in the municipal gymnasium the program was carried out a bit faster and at Czacki I was almost a month ahead of my colleagues. Therefore, I was surprised when Sobolewski, welcoming the new student, said that he gave me 4 weeks of time to adapt to the level of the state gymnasium.

On my birthday on January 16 – I remember it perfectly – he grabbed me to the blackboard and asked for proof of Thales’ theorem. The question was child’s play, I carried out the proof on the blackboard in a few minutes without errors and I got for a poor drawing, two, the first and only in my life in mathematics. There was a test in February, which gave me 4+. I learned that when I got down to work, I managed to adapt to the requirements of the state gymnasium. From then on, we lived in harmony with Professor Sobolewski.

During the occupation, after a math lesson in the so-called sets taking place in our apartment, in an interview with my mother, prof. Sobolewski found out that her maiden name is Sobolewska. However, they did not find any common affinities, only the common coat of arms Ślepowron. He admitted then that every new student coming from a different school always got the first unsatisfactory grade so that he would know what Czacki’s state gymnasium was.

Of my colleagues, I remember my friends best: Zbyszek Przestępski (he was with me in the Warsaw Uprising and died on August 2 near Boernerowo), Wacek Koc (the nephew of Colonel Koc, the founder of OZON, died a few years ago), Stanisław Likiernik (the son of an officer counterintelligence in Germany, lives in France), Aleksander Tyrawski (died in the Uprising in Żoliborz), Olek Pietrasiński (died a few years ago).

With science – as before – there were no special problems, except perhaps Latin. However, at the end of the fourth year of junior high school in June 1939, good Watermelon gave me a four in this subject, which I certainly did not fully deserve. I had to give him my word of honor that I would definitely go to a high school of mathematics and physics, where there is no Latin, and I would not embarrass him. Thanks to this assessment, I did not have to pass the so-called I was admitted to high school without an exam, with good grades in all other subjects, and very good in mathematics and physics, and French. However, after the end of the school year, dangerous clouds hung over my further studies with Czacki. In good humor, my father later joked that I was saved by … the war. But that is a completely different story.

MB

(excerpts from MEMORIES FROM THE PRE-WAR, WAR AND THE FIRST POST-WAR YEARS)