Family memento – Poland – Memories of “After the Uprising 1944” part I

Fragment of memories

“After the Uprising”

Part I:

From the capitulation of Żoliborz to the last days of October 1945

Hospital

In the early afternoon of the last day of the Uprising in Żoliborz, I was wounded on my right shoulder. After putting on a drop dressing at the sanitary station, I was taken to the insurgent hospital in the old fort in Traugutt Park. There was a small argument at the entrance to the fort as I was asked to give up my weapons. The explanation that I brought this drop-down revolver myself from Kampinos and that it saved my life during the second attack on the Gdańsk Railway Station did not help. The shot hilt was viewed with curiosity, but the revolver had to be returned in the end.

In the hospital in the fort, I met a doctor I knew, my father’s friend [1]. She examined my dressing. It stated that it is well put on. I also learned that I was very lucky: a few millimeters to the left and the bullet would crush bone, a few to the right – it would cut the artery (or maybe the other way round – I don’t remember). “These are the last hours of the Uprising,” I heard, “I have nowhere to put you, there are badly wounded everywhere. Find a place somewhere where you could even sit ”.

In the alcove, right next to the entrance to the fort, there were the dead and the dead in the hospital, who could not be buried during the day due to a very heavy fire. There was some space by the wall. It was even possible to lie down because of poverty, of course on the bare ground. It didn’t matter to me. I sat down against the wall and began to doze immediately. After a while, “my” doctor brought me some alcohol in a glass: “Here you have a drink, it will do you good”. It must have been pure medicinal spirit; it was terribly strong. I immediately felt dizzy and the movie stopped. When I woke up, it was already light and eerily quiet.

Gdy obudziłem się, na dworze było już widno i niesamowicie cicho. Only rarely, long single shots came. Some nurse helped me up, probably very surprised that one of the dead was trying to get up – after all, I was lying among the corpses.

She took off my drop-off English uniform jacket and put on her women’s black summer coat with a velvet collar. She explained to me that the Germans had been informed that there were no insurgents in this part of the hospital, only civilians. I was still semiconscious from exhaustion, and I was not quite aware of her arguments, but I did not defend myself against this change. I was only surprised that it was the end of the Uprising.

I was given some cold lura to drink that was supposed to pretend to be coffee. She was quite sweet. “I poured the rest of the sugar,” I heard from the nurse, “it’s a pity to leave it here, and I don’t know if it could be taken. I sweetened the grain coffee. Let the people drink at least. Here are a few more dice, put them in your pocket. ”

After a while, I heard loud orders from hospital staff that the wounded who could walk as well as the civilians who hid in the fort go outside. I walked out in front of the fort and was blinded by the light – the sun was already quite high; the day was clear. Only now was I able to realize my appearance. I was dressed in green denim pants, German army boots, a shirt without a right sleeve that was torn off when putting on a dressing, and a ladies’ slightly tight black coat with a velvet collar that must once have been quite elegant. In addition, a hand in a sling and a beard at least two weeks old on the face. All in all, I had to look interesting.

Enslavement

In front of the fort, on both sides of the park alley, stood soldiers in SS uniforms with automatic machines ready to fire; as it turned out later – Ukrainians or Russians. We went out, as instructed, “hands up”. My right arm in a sling; and a ladies’ coat with a little too short sleeves on the left, raised arm revealed a watch; a gift from my father for the 21st birthday (in January 1944). One of them, in an SS officer uniform, stopped me, looked at my watch, and tore it from my hand without bothering to unfasten my belt.

We were formed into a column. I was in her front part; I was one of the first to leave the fort – I stayed overnight right at the entrance. We walked through Powązki and Wola. In the church in Wola, I remember a short rest. In the evening we got to Pruszków. I can’t remember if we were on foot all the time or if they picked us up by train. An absolute break in your curriculum vitae.

Here I owe a little explanation: on the third day I had nothing in my mouth (except for the “medicine” in the fort hospital). While resting in the church of Wola, some soup and bread were distributed. I did not get to the bread; I didn’t get the soup because I didn’t have anything to take with it.

How I slept my first night in the railway workshop hall in Pruszków (which served as Durchgangslager – a transit camp) – I do not know. I woke up early in the morning, freezing cold and wildly hungry. I remembered the sugar cubes in my coat pocket. They were very useful now. I had no luggage, nothing kept me in my place of accommodation. So I went “for a walk” in the hall to find out about the situation. It was not easy, there were people everywhere, many wounded and sick, bundles, suitcases … It was difficult to find a place to put your feet up.

At one point, I heard a soft cry. A female voice repeated my pseudonym “Zdzich”. In the dark and monstrously crowded hall, I couldn’t see who was calling or if it was for me. I managed to get a little closer and I recognized the lady I saw in the insurgent hospital on Krechowiecka Street, where I visited several times injured colleagues from our company. Finally, I hardly got to her. She was holding a piece of dry bread in her hand. At that moment, I felt an incredible hunger. I think it was evident on my face, because without asking, she took a hunk of black, assigned bread from her bag and handed it to me. It tasted like the best cake.

“We need to do something with you quickly,” I heard. “The Germans are about to kick you out of here. How did you get here among the civilians? It says on your face that you are an insurgent and should be in captivity. It’s probably a miracle you made it here. They caught people like you along the way; some were even shot on the spot. Why didn’t you go out with the wounded insurgents? Wait here. I need to arrange something for you soon. We meet at this pillar when – I don’t know, but be sure to wait ”.

She went deeper into the hall, managing efficiently avoiding lying people and their luggage. I sat down on the floor and fell asleep immediately. Then I was able to sleep in any position and situation. I had huge arrears.

I was awakened by a violent tug on my hand. Someone was taking off my coat and unrolling the sleeve of my shirt, the only one left for me. I saw a woman in a white coat leaning over me, a syringe in her hand.

“You are crazy (my dictionary at the time was not very elegant) – this is the left hand, and I am wounded in the right. Why do I need this injection? ”

But I got the injection. When the figure in the white apron was raised, the stranger I expected appeared and said softly in my ear: you got an injection of milk, an ordinary cow’s milk, but boiled. You will soon get a high fever – this is the body’s normal reaction to a foreign protein. We will diagnose typhus and you will be transferred to the typhus barracks. We’ll try to get you out of there.

Everything went according to the program, with the only correction that I got a very high fever and shock, so that apparently they barely saved me. I was unconscious for two days. On the other hand, the German doctor who decided to transfer to the hospital’s typhus barrack had no doubts as to the correctness of the typhus diagnosis.

After regaining consciousness, I was so weak that I did not have the strength to speak. But I was always hungry. We were fed quite well there. I don’t know where the food came from. It was certainly not just normal German allocations. Two days later, “my” nurse in a white coat with a red cross headband came and said: “You’re going out tonight. The Germans are too interested in the hospital, they must have sniffed something out. We have more typhus patients like you here.

I couldn’t believe I could get out. The thing was not to go through “Wacha”, because the typhus ward was practically not guarded, but I did not believe that I would be able to stay on my feet. And yet, dressed in a white apron, with a red cross headband, I went out with “my” nurse, carrying with her a large basket – fortunately empty – for bread for the hospital.

Here is a break in my biography again. I remember vaguely that for several days I was lying in a small house, fed intensively. The hosts were simple people, probably railwaymen, and they hosted, apart from me, two Warsaw families with small children.

Unexpectedly, my strength was recovering quickly, the shot arm did not bother me too much. I was very worried about my parents and my sister – they lived in the Old Town area – I knew nothing about them. As soon as I felt a bit better – against the warnings of the hospitable hosts – I decided to go out and try to learn something about the family. Maybe I can meet someone I know.

I left and … after two hours I was back in the same camp. The first patrol I encountered stopped me. They had no doubts what to do with me. Fortunately, it was a Wehrmacht patrol and they behaved calmly, even dispassionately.

Popped in in an idiotic way. Only that now I was in much better physical shape, and I also knew a bit about the camp’s activities from my own modest experiences, and above all from the information that kept coming to my hosts.

I ended up in the same hall where I was already. I now knew that its “contents” were sorted according to not very clear criteria: for work in Germany, to concentration camps, while old men, women and children were generally taken to various places in the General Government. Of course, I was only interested in the latter group. But it was hard to classify me as old men and women, and I didn’t look like a child. I already knew that the transports to the General Government depart from the neighboring hall.

I was quite rested and fed, so at night I did not go to sleep, but wandered around my hall, going out in front of it, to the barbed wire surrounding it. There were more people who liked jumping to the neighboring hall. At the gate, a group of women and children negotiated with Wachman to let them pass there. There were bottles of vodka on the move (where did they get it?), Probably also rings.

I came closer, put on a piece of motley nylon made of parachute (from the Kampinos airdrops – I kept it as a souvenir; in the back pocket of my pants, so it survived during the exchange of “uniforms”), just like country women do, and when a market was struck at the gate, I ran and a group of a dozen women with children, as well as a few men who grew up out of the ground, holding a terrified little girl by the hand, I ran to the neighboring hall. The night was dark, blackout was in effect. The sentries shouted something, two pistol shots were fired, but nobody was hurt. All this hustle and bustle was supposed to serve only as an alibi for the sentries. Several Germans entered the hall, they shone their torches on the lying people, they talked in the passage for a while, and… they left.

After a long moment, I went to the other side of the hall. I learned that a transport to the General Government was just being formed. So there was a chance. In the dark hall, my age and unusual clothes (still the same, only the shirt in the railway den with two sleeves) did not pay much attention. I approached a family with three young children and relatively large luggage. Without going into details, I said: I have to get to this transport with you. They were not thrilled with this proposal, but they did not refuse to help.

I was given a huge bundle to carry. The oldest boy, probably eight years old, immediately understood the situation: “Carry him so that you cannot see his hand in a sling. I will help on the other hand. ” Another headscarf and we are already in the car. It is an open coal car, clogged so that there is no way to sit down. It was with great difficulty that the children were seated on the bundles. I put myself in the corner of the wagon. Luxurious place, there was a very good support in the corner, you could sleep standing up.

A light rain began to fall. After a short wait, the train started moving. There were women, children and a few older men in our car. In the neighboring ones, as I could tell when it got light, the passenger line-up was similar. There were armed Germans in the guard booths every few wagons.

According to the information obtained in the railway den, such transports were sent to various places in the General Government and located in villages and towns. However, I was not fully convinced that this was true and decided to leave as soon as the opportunity arose. here were more of such wise people on the train. They tried to flee shortly after they departed. The sentries were firing. With what effect I do not know. It was raining and it was very dark. I think there was a good chance of escape. However, I believed that we were too close to Warsaw and that there must be numerous patrols catching escape enthusiasts. Soon it got light. There was no question of escaping now.

The rain had stopped but the day was overcast. The train lingered, stopped at small ignition locks and in the middle of nowhere, it passed military transports. The next night, it passed Jędrzejów and Miechów. We were getting closer to Krakow, but also to Oświęcim. I decided to run away without delay. I did not want to check whether the information obtained about the destination points of transport was correct. I was hoping that the watchmen, all those I have seen much older, are also tired. I have not seen them changed.

At a certain bend, the train slowed down considerably. It was dark, a light rain drizzled again, trees, perhaps a forest, could be seen close to the track. With difficulty, because my right hand was unusable, I pulled myself over the edge of the back wall of the car and slid between the carriages, standing on the bumper. One last glance at the slope of the embankment, whether there is a telegraph pole, culvert or other undesirable obstacle here. pushed off with all my strength and rolled over the side of the embankment. None of the sentries noticed anything. I didn’t hurt my injured hand, I wasn’t even scratched.

I waited for the train to pass and the last car to disappear around the bend. I got up and walked, it seemed to me, into the forest. It turned out, however, that it was not a forest, but a clump of trees with fields behind them. I didn’t know where I was, I didn’t have a map or a compass. All I knew was that I had to get away from the track as soon as possible.

I walked on. After a long walk through the field balks and walking three or four [2] kilometers, I saw the outlines of some village buildings. I sat down in the ditch and listened. The village was asleep, but the dogs were talking, and the cattle in the barns. I came to the conclusion that there are no strangers in the village. This is not how a sleeping village sounds when there are strangers in it.

I entered the village. Dogs started their concert, I knocked on one of the first huts. I was not mistaken, I found good people who welcomed me into their roof at night, knowing nothing about me and asking nothing. It was the village of Iwanowice Dworskie near Słomniki.

Iwanowice Dworskie

In the village, I came to the house of a young couple with three young children. The oldest was four years old, the youngest – several months. They asked for nothing, gave them food and laid them on the floor on a mattress under the blanket. I don’t know what time I got to their home. I have completely lost track of time I guess it must have been past midnight. In the countryside, it is not the most appropriate time for visiting.

The next day I woke up quite late. The traffic in the cottage was full when I woke up and for a while I couldn’t figure out where I was and what was happening to me. The hosts and their children had already finished breakfast. When, after getting dressed and ablution in the yard by the well, I returned to the cottage, I was given a piece of home-made bread and a plate of mash milk. After breakfast, I tried to help my hosts with their work. But they didn’t want to hear about it. “You’re wounded, rest a bit; you can see that you deserve it. You can watch the children. ”

I was in Iwanowice for about five days. I lay on my mattress for two days – I got a high fever in the evening. I don’t know what happened to me. My hosts looked after me. I remember that they gave me some very tasteless herbs. After two days the fever had come and gone just as suddenly. However, I felt very weak.

In the evening, the host took me to the presbytery to see the priest. The priest, who was much older, was evidently prejudiced about our visit, because he knew that I was a Warsaw insurgent, that I was wounded in my hand, and that I was lying down for two days with a high fever. He told me all this as a greeting and added that he didn’t need to know anything else about me. He called his landlady, and together they stripped off my arm. They washed my wound with some liquid, covered it with disinfectant powder and applied a new dressing. It was evident that this was not the first time they had dealt with the dressing of a wound.

After these Samaritan activities, the priest invited me and my host for a “modest meal.” We sat down to the table, where after a while the hostess brought a bowl of dumplings with meat. We got up and the priest began to say a prayer. I could see that he was clearly pleased when I switched on and found I knew her words.

After supper, I asked to contact the local branch of the Home Army. I got an evasive answer. “The foresters come here from time to time, usually quite unexpectedly. When they appear, they will notify me – apparently despite the warm welcome and pleasant conversation, they were afraid to talk to me completely openly. No wonder, they didn’t know anything about me

So I asked about the nearby estates and the names of the owners; maybe I know some of them. This question was accepted with a clear reserve. I learned that in most of the estates there are German troops or there are German administrators and I should not appear there.

I said that I could not sit here any longer, because I was obliged to make contact with the Home Army, I am a soldier after all and no one has dismissed me from the oath, and in the event of a denunciation of someone, always possible, or of the accidental arrival of the Germans, I risk my hosts with my presence. I got an evasive reply that the Germans were rare in this area and there was no need to be afraid of denunciations. There was one in the village who reported, but he has been biting the ground a long time ago.

The next day was beautiful autumn, warm weather. The road through the village ran along a shallow ravine. I sat down next to “my” homestead at the edge of its escarpment and basked in the sun. After some time, a lady about 50 years old joined me, dressed “in town”.

She apologized for bothering me, but she is also from Warsaw, she got out through Pruszków. He’s here with relatives. She found out about me and would like to talk. Maybe I met someone from her family during the Uprising by chance. There are no news of many relatives. I talked to her for a long time. She was glad when I told her that I fought in Żoliborz. Her close cousins lived there. She knows nothing about them, because she herself was in Wola during the Uprising. He is very concerned about them.

It was only after a long conversation that I realized that for a person who was in Wola, and therefore left Warsaw in the first, at most, second week of the Uprising, he knows too well what was happening in Żoliborz. At first I was scared that she was a substitute German informant. After a while, however, I came to the conclusion that “rolling” me did not require such complicated operations. It was a clear result of yesterday’s evening visit to the rectory.

In the evening, my host asked me if I had relatives or friends in Krakow. I answered truthfully that I have no relatives, but I have friends. I was thinking about Miss Kramarzówny, whom I met during my last pre-war vacation.

“You can stay here, but the priest said it would be good if the surgeon saw your arm, because he doesn’t like something there. In this state, you are not suitable for the forest, so if you have the opportunity to mine yourself in Krakow, it might be better to go there. But if not, you can stay here until you regain your strength and power in hand. I didn’t like sitting idle in the countryside. So I replied that I would like to go to Krakow, but how to do it? The first German patrol will pick me up from the train, and on foot a bit too far.

Tomorrow morning, a car from the dairy goes to Krakow, all trusted people. They will drop you off in front of the city, because there is a detailed control at the tollgates. They will show you how to get to the city through suburban alleys.

I made up my mind immediately – I’m going tomorrow. But there is one problem. I cannot ride in green, military, pants and a ladies’ coat. “I can exchange trousers with you – we are of the same height, but I can’t buy a coat.”

The next day, at dawn, I thanked my hosts warmly for their hospitality and help. As a farewell, I received a loaf of home-made bread and a piece of smoked bacon, wrapped in clean white linen and placed in a bag made of thick linen with a shoulder strap. The host took me in a cart to the crossroads, where he was to hand me over to the guards from the dairy.

After a few minutes, an old Opel truck converted into a “Holzgaz” (wood-fired gas generator) arrived. I was placed on the chest, under the cloak, behind the milk cans, under the pile of sacks, right next to the forward side. They warned me that there was a checkpoint a few kilometers away, but I shouldn’t be afraid of anything, just be quiet and not move.

I said goodbye to my host and the car started moving. After about 10 minutes of driving, we stopped. There were German voices. someone lifted the back of the sheet. From conversations with the workers riding on the crate, it appeared that the controllers knew them well. They didn’t check any papers. They got a bubble of cream, a packet of butter and we drove on. I don’t know how long we drove. It was terribly uncomfortable for me to lie on the planks of the car chest, pinched with bags and knocked over by some empty boxes. Finally the car stopped. I struggled out of my corner and hit the ground. I was so numb that I moved for a moment like a paralytic.

Cracow

“This is the end of our ride together,” I heard. “One kilometer beyond this bend is a checkpoint again, but there is no chance of transporting you there. You have to walk from here. Be careful, because there are many refugees from Warsaw in Krakow and the Germans are organizing manhunts on them. You have no certificate of release from the camp in Pruszków. Certain prison or concentration camp if caught. ‘

I was given detailed instructions on how to go so as not to run into known permanent German posts. Of course, there were also patrols, but these had no fixed routes, and one had to count on luck not to meet them or to see them from a distance far enough to pass them. The instruction was long and very complicated. I didn’t know the city at all. I was in Krakow on a trip with my parents and the last time with the school shortly before the war, i.e. five years ago. I was oriented in the very center of the city, but I did not know the street names (moreover, now most of them had changed names). I had no idea where I was at the moment. The name of the suburbs given to me meant absolutely nothing to me.

I said goodbye to my travel companions, thanked them for the lift, accepted the good wishes, slung the strap of the pin bag over my shoulder and followed the directions given.

I don’t remember the details of a walk to the city center at all. I did not have any destination, as I did not know a single address in Krakow. I finally landed in

the plantations and felt very hungry. So I sat down on the nearest bench and took bread, bacon, and my gardening trestle out of my bag and began to eat.

An elderly couple sat on a bench next to me. They were both probably at least 80 years old [3], they were dressed very neatly. He was reading the newspaper, she was knitting. rom time to time they exchanged their remarks in an undertone. At one point, when I was cutting bread, I heard: “Look, Kaziuniu (I remember this diminutive name), how these Varsovians are doing well. We haven’t eaten white bread and bacon for many months ”.

At first I was dumbfounded. I stopped cutting the bread, looked in their direction, and with all my willpower I had to refrain from slaughtering them with the horse in my hand, for this remark was so amazing to me that my first reaction was to shut those hypocritical mouths forever.

I know that those who will read these words after many years will not believe them. After five years of war and the Uprising, the constant threat of death and our daily contact with it, we reacted completely differently than imagined by people living under normal conditions.

I didn’t say a word, but there must have been something disturbing about me as they both jumped up nervously and walked quickly away, looking uncertainly behind each other.

I was furious, but also terrified of this mentality. After all, this open loaf of bread and a piece of bacon are all my fortune. I don’t even have a blazer, jacket or sweater. I wear a ladies’ coat. I lost everything in Warsaw. I don’t know if I will be able to find my friends in Krakow; where will I sleep today; What will I eat when the prog from the good people of Iwanowice runs out? What bloody Krakow centuses. After all, they were intellectuals, not some degenerate bullies. . I couldn’t calm down for a long time. I still couldn’t believe that a Pole, an intelligent man, could speak in a similar way. It’s not that it’s for me. But how can such a thing be said to people after such a terrible national tragedy?

inally, I rolled the remains of my rolling pin into a bag and began to wonder what to do next. There must be an address office somewhere. I will go there and get the address of one of the Kramarzówiens. There were three of them and my mother, one of them must be in Krakow. Yes, but who to ask now about where the address office is, so as not to find similar types as those whom I almost slaughtered with a goat.

Walking through Planty, I saw a public toilet. He appeared on my way just when he was urgently needed. As I was leaving, I saw my grandmother in the toilet cleaning something at the entrance. I asked her about the address office. “It is, of course, it is in Krakow, not far from the street (I do not remember the name), at the police station.”

I was already beginning to be happy that my problems are close to being solved, and here is the end of the expected information. I have nothing to go to the police for. But standing in front of a public restroom is also not the solution. So I went in the direction my grandmother indicated in the toilet.

I remember that the building of the police headquarters was located on a square or on a wide street. I stood at a safe distance on the other side of it and, examining the empty shop windows, watched the headquarters building in the shop windows. There were several policemen under arms at the main entrance, barbed wire entanglements limiting the ability to pass in front of the building, and an unfilled machine-gun nest, covered with sandbags. Few people entered and left the building. Everyone entering, even the officers, had ID cards.

On the side of the building, probably to the right of it, there were groups of people who gave the impression from a distance that they might be refugees from Warsaw, who seemed to enter and leave its side wing. I went in that direction, but keeping to the other side of the street (square?).

I envisioned an elderly lady walking slowly with a cane who might have been one of the people coming out of this wing. When she was far away from him, I approached her and asked if she knew where the address office was.

“But I know, that’s where I’m coming back from.”

“Please tell me if the service there is Polish?”

“Yes Poland. I, too, was hesitant to go there, if it is located in and under the police building. The service is Polish; try very hard to help. Only the crowds are terrible there. You just can’t push yourself. There is not only an address office, but also a registration office. ”

I waited for a while, until a slightly larger group of people walked towards the entrance to the address office, and I walked in with them. Indeed, the crowd was unmerciful there. The queue was already standing on the stairs. In the crowd, my women’s coat and arm in a sling did not catch the eye of people, but on the other hand, longer standing in the queue increased the chance that someone would be interested in me. So I took advantage when the clerk called a few names, admittedly not to the address but to the registration office, and went upstairs with the called office. Nobody paid attention, in the general confusion, to the additional “induced”.

In the corridor, I saw a sign “Address Office”. So I threw in the direction of the clerk at the front of our group, “thank you madam” and entered the room probably avoiding the queue waiting for punishment at the door. Nobody even protested.

It was a very large room divided into two parts by a railing. Before her, about twenty people waited for the possibility of asking for the address – in writing, on the printed forms. Behind her – a few clerks were running between cupboards full of binders and customers. The room was stuffy, and there was indescribable confusion and noise.

A little looser (which does not mean loosely!) Was on the right side of this room. Part of the barrier was fenced off, officials did not approach clients there; there was a door in the railing through which someone on staff would come in and out from time to time. I stood by them and wondered how to cram into one of the informants.

After a while the door opened and an old lady stopped in the aisle. She grabbed my unbuttoned coat, covered my arm in a sling with it, and asked “what are you doing here?” Surprised because it seemed obvious to me, I replied that I was looking for an address. She looked at me as if I was crazy and in a loud voice said, “Oh, how good it is that you finally came, here you have to do something about this door, because it keeps jamming”. She opened the door on the railing, literally dragged me inside; she opened the door to the side wardrobe and pushed me in so that I was obstructed from the sight of most people in the room.

“Lord, it’s full of spies here; every time they take someone out of here; how could you come here; you don’t need to ask who you are. Who are you looking for? ”

At this point, I hesitated. Kramarzówny are definitely involved in the underground. By asking about them, I can trace them. My interlocutor apparently noticed this hesitation. “It’s a waste of time,” I heard, “if I wanted to turn you over, I would have already done it, and they can get the information out.”

Wait a minute, I’ll fill out the form in a moment. “Complete madman, you must have been hurt in the head, not in the hand; do not write anything! ” I finally gave my surname, but changed my name and age. She went away to look in binders. She returned a few minutes later: “She doesn’t live here.” .” I hesitated to provide real data when she added “no one with this name is registered in Krakow”.

I was silent for a long time, I didn’t know what to do or what to say. She must have noticed my worried expression, because she changed her tone from rebuking the reckless boy that she comes to a place he should walk from afar to a more gentle and compassionate one: “You don’t know anyone else in Krakow?”.

Nobody came to mind. We had no relatives or friends, even distant ones, in this city. Suddenly I was struck by an enchantment, because my friend from the Military University of Technology (PWST), Zbyszek Łukowiecki, lived with his parents in Krakow. He came to Warsaw to study. I can give his name without fear, he is definitely not at home. I know that he was in the Home Army and I’m sure he took part in the Uprising, although I have no idea where and in what unit. He found his own way to the conspiracy.

I gave his details. She returned after a while with the address “Kanonicza Street, number …, apartment number …”. For joy, I wanted to kiss her hand. But in both of them she kept some papers. So, without thinking for a long time, I kissed her cheek and started to push my way towards the entrance.

She grabbed my sleeve, losing a bundle of papers in the process. Well, I said, complete madness. Do you know where it is? ” I have no idea. “Then listen, it’s not too far.” I received detailed instructions on how to get there and a warning not to go from the side of Wawel, because police patrols often go there.

I left the building and reached the given address without any problems or adventures. It was a very old tenement house, like all the buildings on this street, badly damaged. The apartment with the given number was on the second (if I remember correctly) floor. I walked in, stood in front of the door, and hesitated. After all, I have never seen Zbyszek’s parents. I don’t know if they know about my existence at all. However, I have no choice but to press the bell and we’ll see what happens next.

At the Łukowiecki family

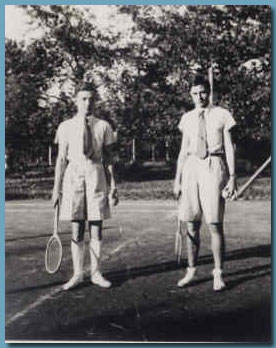

Zbyszek’s mother opened it for me. I introduced myself to her, but my name meant nothing to her. I asked if I found Zbyszek. I found out he was absent I did not know if he was temporarily or not in Krakow. So I added that I was his friend, and also that of Andrzej Krupiński (I knew that their parents were friends behind each other – “My friends and colleagues from the occupation University of Technology – Konstancin; probably July 1944: from the left: Zbigniew Łukowiecki and Andrzej Krupiński (he died at Boernerów August 2, 1944 “).

I learned that Zbyszek was at home at the beginning of the summer vacation, but at the end of July he went to Warsaw and since then they have not had any news about him. After a while, Mr. Łukowiecki appeared in the hall. I had to repeat and swear that Zbyszek was not in the Uprising with me, that I do not even know what grouping he fought in, because he ended up in the underground in other ways than I did and I have no idea what was happening to him.

They asked me into the room and started asking me questions again from the beginning. I had to briefly tell my stories about the uprising. When I finished, they asked about Andrzej Krupiński. I said that I lost sight of him on the march to Kampinos, and I don’t know what happened to him at Boernerow. At that moment, they came to the conclusion that I was hiding the truth from them, and their son had to be with Andrzej and me (they remembered that we were in one “pack” of friends) and he certainly died.

was tired and nervous about this situation. I don’t think so politely I said: “I understand your anxiety for my son, but I don’t know anything about the fate of my parents and sister, I don’t know what happened to them during the Uprising and I don’t know if they’re alive, I don’t know what happened to my fiancée, and the same I don’t know anything about Zbyszek ”. I guess they noticed my irritation because they changed the subject of the conversation. You must be hungry, I’ll get something ready in a moment.” “No, thank you, I still have some leftovers from Iwanowice. I just dream about washing myself well and would love to change my underwear, but I have nothing to change. “It’s not a problem, there are Zbyszek’s things; Please go to the bathroom, I will give you everything I need in a moment.

In the bathroom, I enjoyed being able to clean thoroughly. It can only be appreciated by those who, like me, have been washing themselves for about 10 weeks under the pump or in a kit near the well. And the days when washing was out of the question were no exception.

or washing, I had to remove the bandage from my arm. In the heat of washing away the layers of dirt, I forgot that for my unhealed wound it might not be advisable to soak in water. But it was too late. I was wet from head to toe.

Before the war, Mr. Łukowiecki was the starost of Podolia or Wołyń. Unfortunately, I don’t remember the town anymore. He managed to escape with his whole family from the Bolsheviks and settled in Krakow. Officially he was involved in charity work in the RGO [4]). However, I think he really was in the underground civil service.

Immediately after dinner, Mrs. Łukowiecka noticed that I was struggling to keep my eyes open. She offered me to go to sleep, despite the still early hour. I didn’t have the strength to argue. For the first time in nearly three months, I lay in an honest home bed. I fell asleep immediately. I woke up the next day at noon. The Łukowiecki family were already anxious about what was happening to me

Not! I was wrong! I slept in a real bed the night of August 15-16. The “Żubr” battalion moved from Kampinos to Warsaw to Żoliborz in a column of about 800 [5] people, bringing drop weapons and ammunition. We were weighed down like pack mules and we came literally with the last of our strength. Our company “landed” late at night in the yard of the 7th colony of WSM in Suzina Street. The residents welcomed us enthusiastically. With the approval of the command, we were invited to the apartments for a very late dinner and rest

An old lady invited me. I remember that I was washing myself in a real bathroom (although there was no water in the taps), I ate something and I do not know how I ended up in bed. I woke up the next morning in clean sheets, in a room with all the panes and furniture and various knick-knacks in their places.

My old lady, hearing that I was awake, brought hot tea to my bed and home-baked bread with… preserves.

Mr. Łukowiecki brought me an “assignment” of clothes from the RGO: two sets of underwear (two flannel shirts, underpants, socks), trousers made of thick cloth (probably some military ones, dyed dark brown), a jacket that I cannot recall at all and insulated jacket made of German ersatz material. The malicious ones said it was made of paper. However, it lasted until the spring of 1945 and even protected against frost a bit. Finally, I got rid of the women’s coat for good, which so far made me complex and also attracted too much attention with its cut. In the afternoon a middle-aged gentleman visited the Łukowiecki family. He was introduced to me as a friend of the family who had gossip from time to time and was by today too. I don’t know for what purpose they used such camouflage against me, because after a few minutes I had no doubts that it was someone from military or civilian intelligence. The household members left the room under any pretext, and I had to once again tell what happened to me during the Uprising. At the same time, he often interrupted my relationship by asking about various details that were mine

seemed completely irrelevant.

From the first day of my stay in Krakow, Mr. Łukowiecki tried to find out about the fate of my parents and sister. He had great opportunities; due to his work in the RGO, he met many people. Unfortunately, he did not meet anyone who was on Miodowa Street during the Uprising.

He brought me a Krakow newspaper every day. At least two of its pages were filled with advertisements from people seeking each other; mostly from Warsaw. I looked through these ads carefully, but to no avail. On the second or third day, he brought older newspapers, so that I had the opportunity to view probably all the ads that had appeared since the arrival of the first transports of civilians evacuated from Warsaw. Unfortunately, all to no avail. We came to the conclusion that I must, therefore, make an announcement. We agreed on a very short text: “Maciej Bernhardt is looking for Stefania’s mother, Wacław’s father and Danuta’s sister living in Warsaw, 9 Miodowa Street. News at the polite address of ul. Kanonicza nr x, m y

After a few days in Kanonicza Street, I finally got a sleep, had a lot of free time and didn’t know what to do with myself. The apartment was very tiny. I had nothing to do there. I had nothing to do there. After a few minutes, I thought about my loved ones, I was reminded of the images I had remembered during the Uprising. After a few minutes, I thought about my loved ones, I was reminded of the images I had remembered during the Uprising I couldn’t sit still at home. And it was really dangerous to go out on the street in my situation.

After consulting Mr. Łukowiecki, we agreed that I must have some exercise after all. I will be going out in the evening when traffic is minimal and I will be walking from home to the church 250-300 meters away and back. This way I will always “catch” some air and movement.

The next evening, equipped with a borrowed pocket watch, I went for a walk. The idea was brilliant. I missed that bit of movement and air. I walked for half an hour like that, went to church for a while and returned home about a quarter of an hour before the curfew. After the first such walk, I was very tired. However, the form was not the same for me. There were only two such walks. The third ended unexpectedly.

Overnight in the church

I went out for an evening “walk” just like the previous days. I got to the church, turned back towards the house, but didn’t make it to the gate. I was supposed to pay as little attention to myself as possible in the building, because I lived unregistered and no one should suspect that I might be here.

In front of the gate I saw a boy aged 10-12, whom I had seen through the window before, and I knew that he was the son (or maybe a relative) of the caretaker. So I turned back and walked again towards the city center. This time I walked a little further behind the church. The city was quiet, traffic was minimal. People, like phantoms, moved along the darkened streets. I didn’t have a watch, this time I forgot to take with me the big old-fashioned “onion” that was lent to me for my evening escapades. According to my calculations, it was time to come back, the more so that the Łukowiecki family asked not to come back until the last minute before the curfew.

Near the house, I was surprised to see that there were two cars on the other side of the street, and someone was approaching me. In this district and at this time, a car could only mean a “visit” by the Germans. It was too late to escape. Fortunately, it was the son (?) Of the caretaker who was walking towards me; he was playing with a small ball. He hit the pavement with it, caught it, hit it again, etc. and purred something or hummed to the beat of the ball. When we passed each other, I heard “And at the Łukowiecki family, the Germans, at the Łukowiecki’s, the Germans, don’t you come back…” I treated the boy like air; I stopped at the gate of the nearest house and turned back.

What can be done in a foreign city, a few (as it seemed to me) minutes before the curfew, while also having “shaky” Warsaw papers. Passing in front of the church, I went inside without thinking. The church was completely empty. The lights are off, except for the red lamp at the altar and the small light bulb above the front door. The priest was just coming out of the confessional and, looking at his watch, he said to me. “Curfew in fifteen minutes. I cannot confess you anymore, because I will not make it to the rectory. You have to come tomorrow.

“I should definitely go to confession, but now I am brought to church for another reason.” As soon as I could, I explained my situation to him.

“What to do with you?” I heard. “I cannot take you to the rectory. All I can do is lock you up in church. I’ll think overnight and we’ll do something with you tomorrow morning. ” He took me to the sacristy, pulled out a red carpet (probably used for ceremonial weddings) and some old cassocks from the wardrobe. “Make yourself a bed. Only under no circumstances are you allowed to turn on the light here. Come on, stay with God. I have to hurry to make it to the rectory. Not far, but it’s terribly late. And there is a toilet behind the door. He turned off the light and left. A key screeched in the lock.

It was completely dark in the sacristy, I couldn’t see anything. I sat down on the rolled up pavement and closed my eyes, hoping they would get used to the darkness. After a while, I opened them. There was still nothing to be seen. Apparently the window was covered with black paper. An idiotic situation.

With difficulty I unwrapped a piece of the pavement, I felt the cassocks hanging on the chair, which I knocked over on this occasion. I made such a noise that it seemed to me that it must have been heard throughout Krakow and that the police, lured by the noise, would soon come. But nothing happened. It was only from the outside that the cat meowing could hear.

I lay down on the pavement, covered my jacket and cassocks, and tried to sleep. Sleep did not come for a long time. I had some insurrectionary situations, my friends who had died, some pre-war memories. I don’t know when I fell asleep; I guess it’s very late.

I woke up freezing cold. I saw a faint light on the edge of a roll of black paper obscuring the window. I got up and uncovered them a bit. Outside, it was dawning. I tried to warm up. However, the curling of the pavement and the intense exercise did not help.

Time dragged on mercilessly. Eventually I started to doze again. I woke to the sound of the door opening. Two people entered the sacristy: a man in his forties and a young girl. They were not surprised by my presence. Without a word, they took a thermos from their briefcase and poured a mug of hot tea. Please drink; You must have been pretty cold here. They also pulled out a few slices of bread smeared with lard with cracklings and onions, and a piece of cottage cheese.

“Get your fill. You must wait here until afternoon. We’ll come for you when it starts getting dark. You can sit here quietly. None of the priests, altar servers, churchmen, or organists will be surprised about anything or ask anything. It’s better not to show up at church. Not all come for a pious purpose. We have to go. I’ll see you before this evening. ” After a while the churchman entered and started cleaning, a little later two nuns came. Everyone treated me like air. After some time “my” priest appeared. He asked how I slept, advised me to be of good cheer, and began to prepare for the celebration of the Mass.

omeone came to the sacristy from time to time: about baptism, and someone asked for a marriage certificate. Traffic was minimal. Time dragged on mercilessly. It seemed to me that this day would never end.

Around noon, a woman wrapped in a headscarf entered the sacristy. I thought a beggar. She began unrolling the package she had brought with her. A pot of steaming soup and a piece of bread appeared. She put it in front of me, said tasty and added: they will come for you soon. The hot soup and the fatigue of the situation did their job. I don’t know when I fell asleep sitting on the chair. I was awakened by a tug on my arm.

I saw a girl I met this morning and two men. They introduced themselves by pseudonyms. Come on, let’s go right away. We went out into the street. We walked a long time through the city, and then a suburb built up with poor houses. One of the men went first; behind him at a distance of 50 – 100 meters me with a girl; a dozen or so steps behind us – the second. I could barely keep up with the pace I set. I haven’t got back in good shape yet.

The owner welcomed us in a small but neatly kept house. As he introduced himself, he was half a railwayman and half a gardener. We were treated to a modest dinner. The conversation was social-bland. They did not ask me anything, nor did they raise any topics that might expose them. Apparently they disbelieved me. I couldn’t be surprised – after all, they didn’t know anything about me. After dinner, I found out that I would be passed on the next day.

The hostess took me to a tiny room in the attic. The hostess took me to a tiny room in the attic. There was a basin on the stool, next to it a watering can and a bucket. You can wash up here and have a good night. The light switch is downstairs by the stairs. If you’re ready, please knock on the floor, we’ll put it out. It was warm in the room, but the couch was terribly uncomfortable. Satisfied, it collapsed halfway, the springs pinched the cover and creaked at the slightest movement. Still, it was better here than yesterday in the sacristy.

The next morning, early in the morning, after breakfast, we drove a steam-horse wagon

loaded with potatoes, cabbage and similar specialties to the market in the village, the name of which I had never heard or remembered before. Apart from the host and me, there was also a man who had been our “rear guard” the previous evening. We drove for quite a long time, I think it was at least 5-6 kilometers. The market was located in a small town, or rather a large settlement. Trade was poor, but around noon our car was almost empty.

Around 2 p.m. a girl appeared, the same one who “looked after” me yesterday. Upon my remark, after saying hello that the liaison officer had not yet reported, she replied: “what is it, I am here, let’s go in a minute”. She spoke to my companions for a moment, said goodbye to them, and we set off. I was prepared for a long walk and I was a bit afraid if I could do it, because I could still feel yesterday’s hike in my bones. We walked along a side country road, then along dirt paths, through some grove. Like yesterday, all attempts to establish a conversation were dismissed by my guide in silence or given in monosyllabic responses, not encouraging further conversation.

At the partisans

We walked for quite a long time; I think not less than 2 hours; in a small, sparse grove we heard: “Whoever is walking, let one come closer and tell you the password”. We were stopped by a partisan detachment. My guardian signaled me to stay where I was, took a dozen steps, gave me a password that I did not understand. After a while, she came back to me with three armed men. It was obvious that they knew her very well. They also knew who I was from her. They introduced themselves with pseudonyms and watched with undisguised curiosity what a real insurgent looked like. I, on the other hand, looked at what the partisans near Krakow looked like. They were dressed rather in civilian clothes, and if not for military belts on jackets and forage caps with eagles, they could have passed for civilians. They were well armed. One had a German Schmeisser submachine gun, the other a rifle, third parabellum gun; all of them had German grenades stuck in their belts

The one with the rifle joined us and the three of us went to the buildings visible at a distance of about half a kilometer. It was quite a large village. The command of the Home Army partisan unit was quartered there. In the dairy building we found a lieutenant, a sergeant and a civilian standing aloof. I checked in according to the rules. I saw that it was appreciated. They gave their nicknames as well as the number and name of the branch. They welcomed me very nicely. They knew that the Warsaw insurgent would be delivered to them from Krakow. I briefly presented them my uprising fate and my escape from the transport. They listened without asking any questions. They were only interested in how my wound healed and said that in a day or two the doctor who looked after them was to come to the ward and instructed the sergeant to make sure that I was examined by him.

In conclusion, the lieutenant said to me in a polite but formal tone: “We have no doubt that everything you said is true, but you yourself understand that we need to check it; for now you are assigned to the provisioning group and we will not give you a gun, besides you are wounded and exhausted, you deserve some rest. Tomorrow you will get the paper and you have a whole day to write the record of your service in the Home Army, especially during the Uprising and how you avoided captivity ”.

“Do you have anything to write about? A pencil, no! it has to be written decently, you will get a pen; do you understand what i am asking? Not only do we want to learn more details about the Uprising, but please also provide facts that will help to identify you. Now, sergeant, please take the cadet to the quarters, provide some supplies and look after in general properly. ”

The next day, as announced, I received a few sheets of checkered paper, a pen holder with a nib and a school inkwell. To my remark that I can no longer write with such an instrument, a fountain pen, even quite good, was borrowed from somewhere.

I sat down at the table in the cottage and began to write. It was very slow for me. I never imagined that the two months of the Uprising and almost a month later wandering would have such an effect on me. I couldn’t put the sentence together correctly. The text seemed terribly coarse and clunky to me, and I had trouble figuring out the sequence of events. I remembered many of them perfectly, sometimes even with the tiniest details.

At the same time, it was difficult for me to figure out what happened before and what happened later; nicknames were wrong. Some of them I couldn’t remember. I had already written a lot of paper, and it was far from the end and it did not add up to a reasonable whole. I began to fear that my “essay” might make me a suspect.

My struggle with my own memory and stubborn pen was interrupted by lunch (very good and plentiful). At the end of it, the civilian who had been present at my first conversation the day before came, and he did not interfere at all at all. He greeted everyone present and asked me if I was finished. I replied that I had not yet mentioned the unexpected problems and difficulties I had encountered. He didn’t answer anything, changed the subject and joined the general conversation about the war situation.

After dinner, he asked me to the next, empty room. He introduced himself as an intelligence officer and said he needed to talk to me. He asked for my essay and

read it carefully. “Well, it’s not as bad as you said. I am asking for pseudonyms or surnames and units in which they served, people who know you and can confirm your identity and participation in the Home Army and the Uprising ”. Well, you still have time for that until evening, now let’s talk. ”

The guy looked very inconspicuous, but he was extremely bright and very intelligent. For example, he asked me for the names and surnames of my close and distant relatives, people I knew well. Two names definitely interested him: my uncle Rzewnicki – a retired electrical engineer and quite well-known mountaineer before the war, and a friend of my father – judge (or prosecutor) Stypułkowski. When it turned out that I was a student of the Military University of Technology (PWST), he asked to name a few professors, and at one of them he asked “what was the subject he lectured?”. When I told him that “machine parts”, he asked me to explain to him what this item covered. When it turned out from the conversation that during the Uprising I operated the “Piat” drop anti-tank grenade launcher – he asked me to describe it and state how it is loaded,

Then he was interested in where I missed my mark in Krakow. I gave the name and address of the Łukówcki family, I also added that they were very worried about me and here I told why I gave up visiting them. The guy looked at me, grimaced, which was probably meant to be a smile, and added in a tone that was now quite unofficial. “Don’t worry about that. They already know you’ve found contact with us. They were looking for you through the appropriate underground services. ”

I was glad “they were very kind to me and I didn’t want to cause them any anxiety, they have enough worries about their son, who was in the Uprising and they don’t know anything about him. Plus, now I’m no longer a suspicious guy with whom nothing is known. ” At this point, he interrupted me and, with a slightly less official face than at the beginning of the interrogation, added: “We still have to check you according to our requirements. Before supper, I’ll send a – as you called it – an essay here and we’ll put it into a normal course. ‘ Feeling much more confident now, I joked “but will it be possible to clarify everything before the end of the war?” “Don’t worry about that. The war is over, but you will still have time to recover.

The following days were rather boring. I was prescribing some provisioning settlements, I used a wagon to get food to neighboring villages. I helped prepare transports of food, linen, soap, etc. for forest units. But I was not allowed to go to them. “You must wait for the verification to complete.” Nice story, I thought, it could go on for months. My colleagues are either in captivity or dead, so how can I verify the information I have provided? Without it, until the end of the war, I will have to count loaves of bread, bars of soap, deliver dirty linen of partisans to wash in the cottages and complete clean ones, etc. Nice prospect, no what!

The next day, I was called to the doctor who came for the previously announced visit to the ward. I was informed that I was to report to him. He officially came to the village and at the local primary school he received the villagers and patients from the area, including partisans. He was an old man, probably in his sixties, a typical “omnibus” village doctor; jovial and lovable.

“I will tell the lieutenant to let you rest, and as soon as possible, you must have your hand X-rayed.” We said goodbye like old friends.

For the next few days, I had nothing to do. As instructed by the doctor, I was allowed to rest. On the first day, I was even happy with it, because my classes so far had been hopelessly boring and I was actually still very tired. The next day, however, the inactivity became arduous, and the next few days were therefore simply unbearable. Someone kindly provided me with a few fiction books, but I was unable to concentrate and after a dozen or so minutes I stopped reading. I felt terrible, and my shot-through arm, so far not causing me much trouble, began to remind me more and more of its existence.

About ten days after arriving in the unit, I was called to a lieutenant I already knew. “I have good news for you,” he greeted me. “The information you provided has been confirmed. From now on, you have the full rights of a Home Army soldier. In fact, we had no doubts from the beginning, but we had to follow the orders that were binding for us. ” He shook my hand warmly until I hissed in pain. “Oh, sorry, I forgot the doctor told me something’s not healing your wound very well. You know – he thought for a moment – don’t get me wrong, you can stay in the ward as a convalescent, but I see that you feel bad in this role. We can send you to our den to recover. If you have relatives or friends not too far away to settle in, I would be glad to give you a vacation.

I admit that I do not feel very well in my current role and that the condition of my injured hand is starting to bother me, but in this area I have no opportunity to settle down. I don’t know anybody here. “Don’t worry about it, we’ll find something for you, and when you recover, we’ll be waiting for you in the ward.”

I was about to report back, but the lieutenant clearly wanted a chat that day. He stopped me and we chatted very pleasantly for at least a quarter of an hour. Suddenly it occurred to me that there was actually a place to stay. “I think I have something, Lieutenant. Unfortunately, not in the immediate vicinity, but near Radomsko ”.

“It’s quite far from here, about 100 kilometers. I don’t want to be indiscreet, but I need to know more. ”

My sister, 8 years older, studied veterinary medicine before the war. For several years, her friend from university and friend – Ala Bartyzel, lived with us. Her father was a clerk in the commune in the village near Radomsko (unfortunately I forgot its name already). Ala lived with us throughout her studies, until the war. During the occupation, she came several times to take – like Danusia – the last fifth-year exams. There was no doubt for me that at Ali’s parents’ house, I would definitely be able to stay, and maybe they would know something about the fate of my family there.

The lieutenant was not thrilled with my story. There were strong partisan units in the vicinity of Radomsko and I was able to get a transfer without any difficulties. The problem, however, was getting there. n foot – too far, and very dangerous by rail. Trains on the route Krakow – Warsaw were under strict German control. Documents were thoroughly checked and passengers were searched. Many people were arrested.

“At your age, with a Warsaw Kennkarte and a wounded hand, there is little chance that you will get there. The vicinity of Radomsko is taken over by the Home Army and you may feel quite confident there, but the city itself and the local Gestapo have the worst opinion. It can be a serious problem getting out of the train station and crossing the city, as well as reaching a village a few kilometers away from Radomsko. We do not have detailed data on the situation in that area here. I also have no right to give you the contacts, because it is a private matter and too little important to increase the possibility of exposing our connections. But I will think, maybe a good idea will come to my mind. For now, rest. Bye, see you tomorrow”.

____________________________________

[1] Her name is forgotten. I only remember that until the Uprising she lived on Czarnieckiego Street, near Inwalidów Square, and that she was the aunt of my friend Janek Filipkowski (he died in Mokotów).

[2]) about 6 km according to the map

[3]) that is as much as I am now, when I choose fragments of memories written at the end of the 1940s for Gapa.

[4]) Central Welfare Council – tolerated by the Germans

[5]) According to some publications, around 600 600

Excerpt from the memoirs

Excerpt from the memoirs

Part II.

From the last days of October 1944 to the first days of February 1945

I’m going to Radomsko

he next day after lunch, I was unexpectedly summoned to the lieutenant. I found him a “civilian” from an interview. “We know that you have survived, issued in 1943, a genuine (though” left “) ID card from a company that collects scrap metal in Warsaw, valid until the end of 1944. We came to the conclusion that you can travel relatively safely to your friends near Radomsko. You will get an “almost real” document from a company dealing with the supply of scrap metal to smelters in Silesia, stating that you are going to a really existing scrap collection point in Radomsko to speed up deliveries, as well as a certificate that you have been released from the transport of evacuees from Warsaw. Nobody is able to check the latter. Hundreds of thousands of people have been transported and there is no record of them, so everything will look quite real. We will also give you a backup, emergency contact in Radomsko, if you are in trouble.

I left at dawn the next day. By car to the nearest ignition switch, a side railway line. There I got on a passenger and freight train going (or rather dragging) to the nearest station on the Krakow – Warsaw route. The distance was about 30 km. The train stopped at the smallest ignition locks, put the wagons on the sidings; from others he took them. The ride took over three hours. There were no surprises at that time. Before the end of the ride, the conductor came to see me, checked my ticket and said. “We are reaching the end of our route. You will change over there for a hurry. You must have a ticket and a special pass Please follow me at the station.

There was a crowd of people on the platform and a lot of Germans; civilian, military, as well as gendarmerie and police patrols. Our train stopped at a side platform, much less crowded. I got out and followed the conductor to the service room for Polish railwaymen. After a while, two German railwaymen entered the room. They were dealing with some business matters. They didn’t pay attention to me. After a good hour, “my” railwayman finally came. He handed me a ticket and a blank pass. I entered my name and destination in German: Dienstreise (business trip). When asked how much I owe him for the ticket, he was indignant: “You have something, everything is taken care of as needed, and I will collect the ticket from the smugglers. They can afford to pay for a ticket like you.

“The fast train arrives in half an hour. It will be monstrously crowded. Please do not push towards him and wait patiently. We are attaching a third-class postal and one passenger car here, but when all passengers are already crammed into it. I’ll tell you where to stand, you will surely get inside. ”

The railwayman’s forecast came true to the letter. The train arrived on time and the so-called “Dantean scenes”. In addition, while the train was still standing, the Germans checked the passengers’ documents and pulled a dozen or so people out of the wagons. At that time, I was sitting comfortably on a bench on the platform and reading in a newspaper about the heroic retreat of the German army and bandit raids on German cities, as a result of which only hospitals and museums were destroyed, and old women and children were killed and wounded.

A few minutes before the scheduled departure of the train, I stood at the place indicated by the railwayman. The postal and passenger car pulled up. The front door stopped almost directly in front of me. I entered the car without difficulty and even found a seat. Within a few minutes of the train’s departure, the wagon filled up “stiffly”. Where did these people come from – I don’t know. After all, the platform was almost empty.

The journey proceeded without any extraordinary emotions, excluding of course the stories of fellow passengers about the trains being shot at by partisans. As I found out later, such accidents did take place. Only the partisans of the Home Army and the National Armed Forces fired at the German holiday trains, while the Soviet one, and apparently also the AL, shot at everything that was moving.

After about an hour, the conductor entered the compartment, accompanied by two gendarmes with characteristic “plates” on their chests. They carefully checked tickets, passes and documents. I handed the ticket to the conductor, and the pass, ID card of the Warsaw scrap metal purchasing company and the letter about the destination – to the gendarmes. They looked through them carefully and gave them with kind attention to a man who works for the good of the Reich’s armaments industry:

“Yesterday there was a raid on bandits (that is partisans) in the surrounding forests and we hope that the journey will go smoothly.” I replied that “I am glad that my business trip was on this date and that I also hope that nothing will prevent me from completing the task.”

Soon after the ticket inspection, we drove to the railway station in Radomsko. “Friends” gendarmes also got off there. At the station, there were two exits from the passenger platform: one for the Germans and the other for Poles, with a crowded crowd. I stood on the platform, wondering if it was better to push with the crowd or wait for the crowd to discharge a little.

The gendarmes who passed by me waved at me: you are on a business trip, you have the right to pass without crowds. There was, of course, police and military control at the door. I had a lively conversation with the gendarmes (at that time I spoke German quite well and with a good accent) about the correctness of their predictions that the journey would pass smoothly. I walked through the gate without being stopped, not even showing my papers.

I was in Radomsko for the first time in my life. I had no idea which way to go, nor in what direction the village of XX [1], where Ali’s parents lived, was located. There were several horse-drawn carriages in the driveway. I went to the first one and asked how far it was to XX. The cab driver replied that it was several kilometers away. Shit, too far to walk, the cab won’t go that far, and besides, I don’t have the money to pay for this course.

“And who are you going to there?” Asked the cab driver, seeing my sour face. To Mr. Bartyzel, a writer in the commune. “He doesn’t live there anymore, they moved to YY, he’ll be two years now.” I didn’t know anything about it. The fact that Ala wasn’t in Warsaw for a long time. Perhaps she wrote to Danusia about it, but it escaped my attention. After all, this was not the most important news for me. There is no advice, you have to go to a backup point of contact. Determined to make an unforeseen change of plans, out of curiosity rather than in the hope that this information might be useful to me right away, I asked how far it is from the village of YY. “And it will be like this from 6 km.” And you are sure that the Bartyzels live there. “Sure, everyone around here knows them. He is still an official, but in a different commune, and his daughter is a doctor of animals ”. Well, now I’m sure the finish line is close!

How much do you take for the course to YY? I don’t remember what the sum was. All I know is that I could afford it. When I went to the Uprising, I had just over 500 zlotys in my wallet. I practically did not spend any of it, because there was nowhere and for what. n Krakow, I got a grant from RGO – I think 300 zlotys. I had no desire and enthusiasm to wander through unknown terrain, asking for directions and people.

Well let’s go. After less than an hour, we were there, arousing quite a sensation, because no one in their right mind spent money on a carriage. Carts were hunted at the market and they returned home in the evening in the desired direction. It cost many times cheaper.

I didn’t know Ali’s parents. Fortunately, Ala was at home, she recognized me immediately.

I was received very warmly. Only later did I realize that when I asked about my parents and Danusia, I got a strange answer that tomorrow we would try to find out something. It was already evening, I was tired of the day’s impressions. I ate a dinner that made my eyes close by themselves. I answered questions with a half-mouth. I remember that Ala changed my dressings after dinner. I don’t know when or how I found myself in bed.

I’m going to Wielgomłyn

The next morning I found out that the Father and our housekeeper Marynia were located in the village of Wielgomłyny, several kilometers away from here. Ala did not see him, but the news spread quickly (even though the phone was only available in the commune and it was surely tapped) and the news about an old doctor from Warsaw, from the Old Town, disabled without a left hand, very thin, arrived shortly after his arrival , that is over a month ago. However, there was no news about Mum and Danusia. I didn’t ask for anything. I realized they were dead.

After hearing this news, I wanted to go to Wielgomłyn immediately. Ali’s parents strongly advised me against it, explaining that “my unexpected appearance may be too strong an experience for my father who is suffering from heart disease. We will try to inform him carefully somehow that you are alive. Maybe someone will go there in a wagon, then you will take it. It is a nice long way to Wielgomłyn, and you can see that you are not in the best shape either ” I guess I must have really looked like this and not feeling well because I gave in.

I don’t know what I was doing all day. A completely white blur in my memory. The next day, around noon, I received a message that Father knows that I am alive, because he received a Krakow newspaper with my advertisement and already knows about my stay here, and Marynia – our housekeeper – is on her way to YY to bring me to Father I do not know how these messages traveled, probably over the phone in the commune, although it was only for business calls and certainly under surveillance.

The next day, around noon, our housekeeper Marynia came to YY. She knocked on the door of the house, greeted her and said in a firm voice, “I came for Mr. Maciej”. She greeted me as if we broke up yesterday and ordered “please collect your belongings and come back, the doctor will be impatient”.

She was hardly persuaded by the hosts that she had already walked a dozen (14?) Kilometers and the same road still awaited her, so it is worth taking a break before her. She was convinced only by the argument that I couldn’t walk that long before lunch. I am wounded, exhausted and I need to eat to have the strength to go this far. Well, she said, let’s collect Mr. Maciej’s things, it’s a pity to waste time.

She was very disappointed that I had absolutely no luggage, Just a change of underwear, a cloth in which the pin was wrapped, a small towel, a piece of soap and a spare handkerchief – it was the “trip” I got for the road. Yesterday I also added pieces of green, motley nylon (it was only after the war that I learned that this new material is called like that) and parachute nylon lines from the arms drops in Kampinos. I cut them off as a souvenir and carried them in my back pocket. They happily survived all my adventures, including the change of pants in Iwanowice. I admit that carrying it with me was actually pointless, as it exposed me during a possible revision to questions that could not be answered reasonably. However, I could not part with them, and so far I had nowhere to leave for safekeeping.

Marynia said that she absolutely would not allow me to carry “this” with me (I must admit that she showed much more common sense here than I have so far). So I gave ‘it’ to Ali for safekeeping. On the farm, it was not a problem to safely hide the rags and a piece of string that fit in the back pocket of the pants. Unfortunately, they never came back to me.

Shortly after that, Ala called us to dinner. Her parents, brother and I with Marynia were sitting at the table. Marynia gave a dry account as if she wanted to ask questions.

On August 26, around 2 o’clock in the afternoon, our house was bombed by Stukas. These were the last days of the fight for the Old Town. Miodowa Street had been on the front line for at least a week. At that time, Marynia was in the basement of a neighboring house, where water was supplied from an artesian well. She went there for water. Father treated the wounded in the basement in the left outbuilding of our house. In our basement (situated in the right outbuilding) there was my mother, Danusia, her eighteen-month-old son Jacek and mother of Hanka, my fiancée, Maria Rychłowska.

After the first few days of the Uprising, Danusia came with her son to Miodowa, because she thought it would be safer there. Mrs. Rychłowska came with her. The bombs fell on the right outbuilding of our house on Miodowa Street and blew it all the way to the basement.

Our basement was located in this part. The rest of the house was heavily damaged, but the cellars and exits remained. Marynia and other survivors tried to dig into our basement, but to no avail. She found her father stunned and completely devastated. She looked after him until the end of the fights, during the transition to Pruszków, in the Pruszków camp, during rail transport to Radomsko, a journey by wagon several kilometers to Wielgomłyn, where he was assigned, along with many other survivors from Warsaw, a temporary place of stay. There is no doubt that the Father lived it all thanks to her alone.

We left YY around 3 o’clock in the afternoon. The day was clear, but already cool. During the march I was even too hot in my paper jacket, but if we were going in a car, I would definitely be cold by now. We walked in complete silence for about three hours, resting only once for no more than 5 minutes. When we got to Wielgomłyn, it started to get dark. In the house where my father lived, a kerosene lamp was already burning.

Wielgomłyny

My father greeted me warmly, trying to hide his emotion. This time he completely failed. “You already know that you don’t have a Mother, Sister, and Jacuś is also gone.”

He wept like a child. I’ve never seen him like this before. He couldn’t calm down for a very long time. nally, suddenly he regained his composure and said in his usual, calm voice: “show this wounded hand of yours; we’ll see what it looks like. He asked Marynia for help. She took off the bandage and the dressing from my hand and pulled up the kerosene lamp. Father looked at the hand from all sides for a long time.

He estimated that the wound after the projectile entry healed very well and in a few days it would be without dressing. On the other hand, the wound after the projectile exit is much more extensive and is still not healed yet. He ordered me to take a piece of paper from the school notebook lying on the table, wrote something on it and asked Marynia to take it to the pharmacy and bring the prescribed medicine. I was surprised where to find a pharmacy at this time. It turned out that there was Mr Dworzaczek’s pharmacy in this town and it was very well stocked. It is worth noting that it happened in a “sunken” village in “deep” provinces, in the fifth year of the war.

My father came here with the first, not very numerous, group of expelled Warsaw residents.

He was very well and warmly received. He was given a room with a kitchen with basic furnishings, bedding, pots, plates and cutlery in a house on the market square. Lingerie, a coat, sweater, towels, etc. were collected in the village. Marynia was also given the most necessary personal items. Fuel for the kitchen stove and basic foodstuffs were delivered. And all this without money.