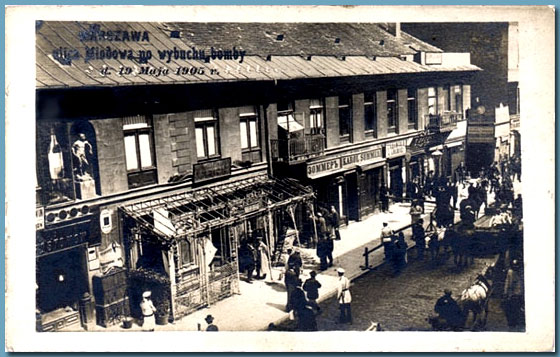

Family memento – Memory: “Childhood – ul. Miodowa, Warsaw in the pre-war period, during the occupation and the Uprising “

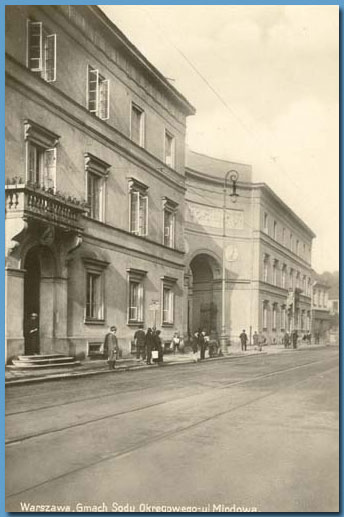

From my birth to the Warsaw Uprising, I lived with my parents at 9 Miodowa Street, in apartment 5 on the second floor. It was my mother’s parents’ apartment. Grandfather Sobolewski was a notary. He had moved to Miodowa Street many years before the First World War to be close to his mortgage law firm. It was really very close to the mortgage: the adjacent corner house (No. 11), and then only a few houses in the ridiculously twisted, cul-de-sac Kapucyńska and there was already a mortgage. Grandpa did not even have to cross the road. Our house stood in the exact place where today is the exit of the W -Z route tunnel.

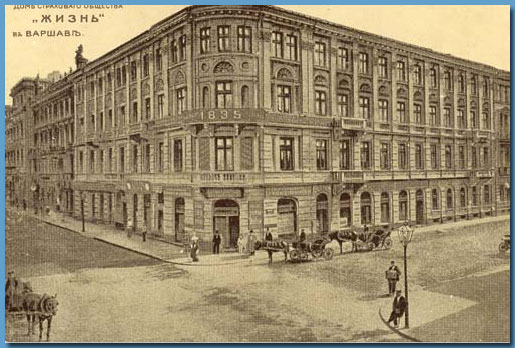

In the period when my grandparents moved to Miodowa Street, it was a “good street”, inhabited mainly by representatives of the bar, due to the proximity of the courts. At number 15 (now the Ministry of Health) in Pac’s palace there was the District Court, at Krasińskich Square – the second, I do not remember what level, and also very close – a mortgage. There were also city residences of many landowners. Of course, I am talking about the front flats, because the outbuildings were usually inhabited by officials of various levels, pensioners, etc.

In its heyday, Miodowa Street housed 17 palaces. In the interwar period there were only 10 of them: Załuski (No. 2), Branicki (No. 6), Szaniawski, Ostrowski (No. 8), Morsztyn (No. 10), Chodkiewicz (No. 14), Metropolitan of Ruthenia with the Basilian Church (No. 18) , Collegium Nobilium (No. 24), Krakow Bishops (No. 5), the already mentioned Pac Palace (No. 15), Archbishops (No. 17). Some of them were so spoiled by the shops on the ground floor that it was hard to guess that it was a palace. Others did not raise the slightest doubt.

Initially, Miodowa Street started with Senatorska Street. In the years 1887-8, the connection to Krakowskie Przedmieście was broken. The new part was called Novomiodowa. In 1921, both streets were named Miodowa and uniform numbering was introduced. As a result of this treatment, our house was changed from number 5 to 9.

In the interwar years, Miodowa gradually ceased to be a “good street”. More and more shops appeared on the ground floors of the palaces, including small Jewish shops, almost exclusively from the fur trade. There was more and more impoverished intelligentsia in the outbuildings.

In addition to fur shops, of course, there were others. The details faded from my mind. However, I remember that at the corner of Kozia and Miodowa there was a representative office of the Lancia car factory. I spent a lot of time with my nose stuck to the display windows, admiring the miracles displayed there.

I suspect that most of the customers were of a similar type, because to my great regret, the car dealership was closed rather quickly and in its place a restaurant called “Raj” was established. She prided herself on the fact that the kitchen room was separated from the dining room by a glass wall, and you could watch the cooks at work.

We have been there two or three times when, due to some domestic failures, dinner was not being cooked at home. Once, my mother saw that the cook was checking whether the cutlet (our cutlet!) Had been salted by putting it to his tongue. It was our last and abruptly ended visit to Paradise.

More or less opposite was Mr. Sybilski’s stationery store. Just before the war, it moved to the corner of Miodowa and Senatorska Streets (today there is a parking lot). The new store was really great: smartly equipped and very well stocked. He only existed for a few months. This house was completely burned down in 1939.

Trojanowski’s confectionery was located at number 6. The place was very old-fashioned and almost always empty. The main clients were probably only pensioners reading the newspaper with a glass of tea or coffee. The confectionery, however, was known to bomb a passing tsarist police before the First World War. I don’t know if the attack was successful and what happened to the bombers. However, I do remember the unveiling of the plaque commemorating this attack in the mid-1930s.

House No. 8 was the seat of the Municipal Workers’ Union. In the yard, in the right-hand back office, there was a well-equipped union library, where I had borrowed fiction books for the last two years before the war.

There was a huge union ballroom on the first floor, at number 8, directly across from our apartment. Every Saturday during the carnival, there would be a muffled rumble of a drum into the parents’ bedroom and the living room until dawn. From time to time the rumble grew stronger – the windows in the ballroom were opened. Things were worse in the “green carnival”. With the windows in the ballroom and in our apartment open, there was no question of sleeping, even though loudspeakers were not used at that time. However, as a result of tenants’ protests, these summer balls ended very quickly.

In the same house, next to the gate, opposite the window and balcony of my parents’ bedroom, there was a fur shop. Unfortunately, I don’t remember the name of the owner. However, this shop and the profiles of its owners stuck in my memory because of a certain puppy joke that I did for them every now and then for about two months …

I fastened on our balcony, between the bars of the decorative balustrade, something between a slingshot and a primitive crossbow, aimed at the glass above the entrance door to the store. I soon got into practice and shot peas almost without a miss, driving the poor owners crazy. They could not figure out where the “missiles” were coming from, because the “throwing device” was hidden behind a decorative forged balcony grate, and I activated the “trigger mechanism” with a string pulled under the balcony door. Through the openwork balustrade you could see a closed balcony door and an empty balcony, and from time to time you could hear a loud “bang”, a hitting of peas against the glass.

A modern Agril store was opened next to the unfortunate fur shop a few years before the war. It was a company (probably a municipal one, but I’m not sure about it) selling very good quality dairy products produced in an estate near Warsaw.

Behind Agril there was a shop with cooling drinks and sweets, which, for obvious reasons, I was very eager to go to, although my father did not express his appreciation about it, because twice there was a “mistake” in spending the rest there, of course to my father’s disadvantage.

At the corner of Kapitulna Street there was Arkuszewski’s restaurant, which was very popular with representatives of the bar. We used to go there for lunch with the whole family during various domestic cataclysms, such as general renovation of the apartment, changing the kitchen stove, and when our housekeeper Marynia was going on vacation for a day or two, ahead of us.

I really liked visiting this restaurant. I loved the bowing waiters and the owner himself, confidentially advising “our doctor and the honorable lady doctor” what to choose from the menu today. There, too, my father taught me that “for good service you should give a good tip; but if they deceive you, even for a penny, you will make a fuss and give you no tip. ” I try to stick to this principle to this day.

The rest of Miodowa Street towards Długa Street was uninteresting for me. On the odd side only the Capuchin church and the district court, on the even number the Uniate church, so hidden in a block of houses that it was easy to miss it from a moving tram.

At the corner of Kapucyńska and Miodowa (No. 11) there was a devotional shop, where I never saw any movement. It was only many years after the war that I read in a book on Polish freemasonry that a masonic lodge was located there.

In our house, on one side of the gate there was a shop – of course with furs – of a gentleman by the name of Złotykamień, and on the other – under our apartment – the pharmacy of Mr. Dobrzański. I was a frequent customer in it, and my father, as a doctor, had an open account in it. To the amazement of other buyers, I often took a whole battery of boxes and bottles from the counter for the purposes of Father’s practice. and sometimes also for the house (on the “pro domo sua” prescription), I would say thank you and leave without going to the cash register.

I have memories from the end of the 70’s or the beginning of the 80’s associated with the Złotykamień company. At that time, I was spending my vacation in Paris. I lived in the apartment of my sister-in-law who was on vacation in Warsaw at the time. It was August, the town was deserted apart from the tourist routes, and many shops had “holiday break” signs.

One Sunday I went for a long walk around the city. I found myself in the area of the old market halls that were just being liquidated. The last houses were demolished to create a place for modern buildings. Above the entrance to one of the shops, in such a partially demolished house, I saw a sign “Zlotykamien”. Through the dirty, dusty glass, you could see the remains of shop furniture and a few people packing something into cardboard boxes.

I stared at it for a while, wondering if the company could have anything to do with Mr. Złotamień’s shop in our house, when suddenly a man, about 30 years old, with distinctly Semitic features ran out of the shop and tried to convince me in an unkindly manner that there is no need to look at here and that my best bet is to get out of here soon.

Surprised, I was silent for a moment, and then began to explain to him what was the reason for my stopping in front of this closed shop. At first he tried to shout over me; suddenly he fell silent and listened attentively to my explanation. He has changed beyond recognition. He repeated several times. Yes, I know that we had a family in Warsaw and I agree that they traded in furs. He grabbed my hand and pulled me forcibly inside the store, shouting at the people bustling around there. Look, he knew my cousins in Warsaw. He knew them!

It was hard for him to understand that I couldn’t say anything specific about them. Their shop was in the same house where I lived with my parents. However, I did not remember what its owners looked like; I did not know if the store had been opened after the September campaign; I thought for a short time yes, but I wasn’t sure. Later it was closed for a long time. One day the sign disappeared and I saw how modest furniture of a war shop, such as “soap and jam”, was brought into the empty interior.

I had to talk about the store in Warsaw several times, about which I really knew nothing. Mr. Z. was extremely cordial and hospitable, he apologized many times for his first reaction. He explained that he was very nervous about closing down the shop that his family had run for several generations.

Mr. Z was active in the textile industry. He was inconsolable that there were no more merchandise in the shop, as he wanted to give me something. He invited me to his warehouse (he gave me an address near Paris) in a few days, when he was done liquidating the remains of the old store.

I did not accept the invitation. I felt very stupid. I really couldn’t say anything about these people. I’ve never been to their shop. I didn’t even know if I saw the owners or sellers through the glass. Two completely different worlds in one house.

On Miodowa Street, in houses no. 7 and 5, there were no interesting shops for me. The gate of house no. 7 had stone protrusions on both sides (they still exist in the rebuilt building), and in each of them there were three round openings, which were supposedly used to block flaming torches.

House No. 5 was a pedestrianized house, you could enter from Miodowa Street and exit on Senatorska, more or less in the middle of the section between Miodowa and Daniłowiczowska (Plac Teatralny), avoiding the very busy corner of Miodowa and Senatorska Streets.

I remembered that much from my street. Part of it, from Kapuchinska Street to Długa Street, left almost no traces or memories of me. Just as I can’t remember what the fur shops, so numerous on this street, looked like. They were generally not very impressive, although, as my father claimed (perhaps exaggerating a bit), each of them contained goods for thousands of (pre-war) zlotys.

I just remember that most of the shops had a clerk or saleswoman standing in front of them and they were literally pulling passers-by inside. Of course, they knew the permanent residents and this method of catching customers did not apply to them. Once upon a time, the salesman, apparently new, necessarily tried to drag my mother to the store, praising that the store must have goods she was looking for. My mother was going shopping of a completely different kind, so she replied, “I doubt it.” “It is, it is, fresh doubts, not unpacked yet!” she heard in response. Until the end of the existence of our home, this saying ran between us.

I remember that all shop windows were covered after trading hours with precisely matched and numbered boards, then pressed with a thick steel bar (or two), closed with a large padlock. Such a closure was quite effective in protecting against breaking the display pane and robbing the store. They were used in almost all streets – even the most elegant ones.

I must also mention a few shops located in the neighboring streets, but visited, or at least only watched, so often that they deserve a mention.

I remember best, for understandable reasons, the Italian ice cream shop “Gelatteria Italiana”. It was located at Senatorska Street, on the section between Miodowa and Daniłowiczowska (Plac Teatralny); More or less at the place where today there is a plaque in honor of the victims of mass public executions during the occupation.

The ice cream shop was open only 5-6 months of the year. It was run by a genuine young Italian – handsome, with great black hair. The ice cream was excellent and the place was always busy. The owner collected the money at the counter. Behind the counter and in the back were a few young girls, different every year, but always of the same type: pale blonde “boned” blondes of classic “blood and milk” country beauty. If rumors are to be believed, the owner valued his ice cream shop not only because of the large income it provided, but also the obligatory benefits in kind of the staff there.

In second place, I must mention Mr. Brzozowski’s toy store, located on Krakowskie Przedmieście – more or less opposite the bell tower of the church of St. Anna (Bernardynów), it would be more appropriate to define “little shop”, as the premises were small. But there is a selection of toys! Soldiers of all possible armies and formations, made of sheet metal, lead and cardboard, rifles, sabers, belts and caps, pistols and revolvers for corks and caps, as well as games, construction puzzles, various sets of “little electricians, builders and chemists” etc. Really It is hard to believe how it could all fit in such a small room, part of which was also – in my opinion completely unnecessarily – some dolls, teddy bears and the like, which should not take up space in such a great store.

On the same side of the street, closer to Miodowa, there was the photo shop of Mr. Bietkowski, our “court” photographer. For as long as I can remember, our whole family took photos for all kinds of evidence and documents, as well as for various festive occasions in this facility. This house was completely destroyed during the Uprising. After the war, Mr. Bietkowski opened his plant in Nowy Świat, opposite the Church of St. Cross. There I took photos for university ID cards, as well as wedding cards. Tradition has been done.

Finally, on the corner of Miodowa (on the odd-numbered side) and Krakowskie Przedmieście there was a “Złoty Róg” shop, which had so many good things that I heard a polite question from an impatient saleswoman more than once, “has the bachelor already made up his mind?” It was very difficult to make up my mind. Most often, after a careful analysis of the advantages and costs, the choice fell on candies called pillows because of their shape. They were very colorful and filled with grille filling inside. For 50 cents you got a really big bag of these goodies.

Almost opposite the Golden Horn, on the other side of Krakowskie Przedmieście, under the pillars next to the Church of St. Anna, there was a cinema. It was originally called “Urania”. Then, for reasons unknown to me, it changed its name to “Los”. My first visits to Urania were related to children’s mornings. However, my mother strictly adhered to the principle that you can only go to the cinema when the weather precludes a walk. At that time, I was very worried about the good weather when there was a good show in Urania, i.e. Pat and Patashon or a set of cartoons.

Then I went to see “normal” movies, but still silent. Urania had an excellent taper (pianist) and I enjoyed listening to his “pieces” during breaks, and then skilfully selected repertoire for the on-screen action.

The cinema room was on the first floor and was very large. A normal ticket cost PLN 0.19 and a reduced ticket cost PLN 0.19. The cash register, though without enthusiasm, was spending a penny of the change.

During the siege of Warsaw, our house was the first house on the odd-numbered side, not damaged (apart from broken windows and minor damage) from Krakowskie Przedmieście. On the even side, all the houses up to Kapitulna Street were demolished and burned.

Our house ceased to exist during the Uprising on August 26, 1944, bombed by Stukas and then burned down. My mother, older sister and her eighteen-year-old son died there.

MB, Warsaw, July 2003

________________________________________

Lockers

In the dining room, in the cupboard, behind the ornate crystal glasses was a silver cup; inconspicuous, with quite thick walls, decorated with a modest pattern. It looked like the “work” of a not very skilled manufacturer. In this cup a double bottom was unscrewed: between them was the seal of the National Government from the time of the January Uprising. It was a steel disc about 4 mm thick and about 35 millimeters in diameter, with a large Polish eagle deeply carved, and a smaller Lithuanian chase and the Ruthenian archangel. The word “National Government” was written all around.

It was a family memento of the Sobolewski family, very much appreciated by my mother. The honor of seeing the seals was enjoyed by very few, and only a few of my colleagues, especially fond of my mother, have obtained it.

Mom was reluctant to take the mug from the sideboard. Always alone, she carefully unscrewed the bottom and took out the seal, which after examining it and carefully wiping it with a similar anointing, she then hid it.

Apparently, in Mum’s young age, there was a document under the seal that filled the empty space and made it impossible for the seal to move. This document was lost during the First World War. In my memory, the role of a filler was a cardboard disc cut from a shoe box …

A large old kerosene lamp, made electric, hung over the dining-room table. It had a lampshade of slightly crinkled pale yellow material, and a wide brass metal rim under the lampshade. There were short strings of milk beads under the rim, so densely arranged that they formed an additional lampshade at the bottom. A simple system of three decorative brass chains, three rings under the ceiling and counterweights in the form of a fairly large ball made it possible to raise and lower the lamp within the range of about half a meter. The counterweight, pressed from brass sheet, consisted of two parts bolted together. Inside was lead shot, the kind used in cartridges for shotguns intended for hares.

At the beginning of the occupation, the pellet was replaced with a similar one, maybe only slightly thicker, but made of gold and very carefully covered with a layer of matte black varnish. The latter procedure turned out to be unnecessary, because during the several searches that took place in our apartment during the occupation, no one ever looked inside the counterweight.

The source of the raw material for the new shot was an old, badly damaged and crumpled gold cigarette case, some old wedding rings, damaged brooches and earrings, etc. “junk”. I do not know how much this “treasure” weighed, I think a lot, because the lamp was quite heavy and otherwise the counterweight would not fulfill its task. I was not allowed to secretly prepare and hide the “treasure”. It had to be done very efficiently, because at that time it was difficult to hide anything in the house from me. I didn’t find out about the secret until mid-1942.

The second compartment, with a completely different purpose, was in the toilet. It existed there even before the First World War. I do not know whether it was prepared by grandfather Sobolewski, or whether it was arranged by the previous tenant of our apartment. It was right under the ceiling – the apartment was very high: 12 feet or approx. 380 cm. Fragments of sewage and water pipes protruded from the ceiling. One of them was relatively easy to unscrew. However, it had a “left” thread and it had to be turned in the opposite direction than when unscrewing “ordinary” water pipes. When unscrewed, it revealed a deep hiding place in a pipe embedded in the ceiling. Of course, this pipe had no connection to either the sewage system or the water supply.

The toilet had a small window to the bathroom under the ceiling. Its matt glass, and probably never cleaned during the occupation, let in so little light that even on the sunniest days the toilet was very dark and the outlines of the pipes under the ceiling were barely visible. The electric lamp hung on a fairly long rope and was covered from the top with a white tin plate. So even after it was lit, the ceiling was always dim.

This hiding place was very troublesome, because placing a ladder in a cramped toilet was a task no less difficult than climbing it and unscrewing the pipe. It was suitable for long-term storage of not very large items or not too thick documents rolled up.

Before the war, my mother used to hide her jewelry and family papers in it, when we all went on vacations and holidays and the apartment was empty. What was there during the occupation – I do not know. Mom didn’t talk, I didn’t ask, I was taught it’s better not to know.

We never talked about conspiratorial work at home. Of course, my parents knew that my sister and I were involved in something, but the topic was taboo. Father was also involved in some underground “medical” activity. There were completely “unusual” patients. Packages of medicines, dressings and basic medical tools were brought and taken out. As it was impossible to hide it from the household members, the official name was that Father’s old friends, displaced by the invaders from Pomerania or Poznań, were organizing their offices here, and the Father and a few Warsaw doctors he knew help them a little.

It seemed to me for a long time that Mom was not involved in any conspiratorial work. There were never any mysterious visits, phone calls, sudden departures, etc. My mother was only occupied with the troubles of everyday life, which were not lacking at that time.

It was only at the end of 1943, or perhaps at the beginning of 1944, after returning home unexpectedly early, that I found my mother struggling to pull the ladder out of the toilet. I helped with this operation and I remember perfectly every word that was said: “Mom, I completely forgot about this hiding place, because now it can be very useful to us.” “Forget it again and completely”. I knew there was no need to ask any more questions in such situations, especially Mum. I suspect that the toilet must have been the so-called “Dead box”, that is, a place of longer storage of documents, operated by a person who was seemingly not involved in anything on a daily basis.

In 1945, after returning to Warsaw, I went to Miodowa Street, to the ruins of our house. There are only traces of the apartment. The remnants of the ruins were only the first floor; our apartment was on the second. Only the burnt walls of the bathroom and toilet were partially left, but there was no ceiling above them, and the storage compartment was in the ceiling. Anyway, even if there were any documents left in it – although I rather think that my mother took them out during the Uprising – they were burnt down like the whole house and those who died in it.

MB, Warsaw, September 2003

________________________________________

Guests

Lots of people passed through my parents’ house. There were parties; there were also “fits”, bridges, kinder balls and regular visits on various occasions. The parents’ name day was celebrated very solemnly. In my early childhood, even several dozen people would come on this occasion. I remember that our housekeeper was assisted by two, and apparently there were even three “borrowed” from my family for this occasion.

Some of the guests came in the afternoon, sipped coffee and ate various delicious sweets in the lounge. Others came to dinner.

Dinners were very sumptuous. Pheasants in feathers were riding on the table. Unfortunately, I did not take part in them, I was too young. But I remember perfectly feverish preparations; I wandered around the kitchen and in the dining room, I was reprimanded alternately for disturbing, then again fed with various delicacies offered by the housekeeper and her helpers: “Let him also know that there are name days at home.” Pheasant feathers were very useful later in playing Indians. There was also alcohol with dinner. In a very limited amount, but of excellent quality: white Rhine wines and French red wines, and the famous liqueurs of my grandfather; and for desserts and black coffee – liqueurs. They were served in crystal glasses. I do not remember if there was also beer, although the technical director of the Haberbusch’s brewery was a regular guest.

After dinner – especially on Father’s name day – bridge was played in the living room for two or three tables. Extendable tables were covered with a green cloth on which the results of the game were recorded. A special chalk was used for this, pressed into thin rolls. The record was wiped off with special brushes.

At the age of 12-14, I was very fond of watching a card game, and as I did not disturb or speak, I was allowed to do so. On one occasion, Father was recalled from the table by the telephone. The auction was over and the opponents were playing. He handed me back his cards and said, laughing, “add to the flush, I think you can.”

Father’s telephone conversation dragged on. The cards were dealt again. I collected Father’s cards and put them in order; someone broke off the bidding, I joined in, and it turned out quite well. At least that’s what Father said when he returned to the game. On subsequent occasions, I more and more often replaced Father in the game. Bridge fascinated me more and more. In the last two years before the war, I played with my friends quite often. I was considered a good player in this company. Mom was very dissatisfied with this because, as she insisted, students should not play cards. During the occupation, I played a lot, often throughout the night. An early curfew sometimes forced us to stay overnight, and as not all our friends and colleagues had the conditions for the overnight stay, we often played cards until the morning. At this point, it should be remembered that there was no television then, and possession of a radio was forbidden under the penalty of death (a concentration camp in the “best” case).

I played bridge even in the first post-war years, although not very often and not as passionately as before. Later, the cards turned out to be gross, the game bored me and in the 1950s I stopped playing completely.

The course of the game was average. After three worms, I was slightly won. And then it turned out that my partners do not count “big” but “small” points, so the stake is 100 times higher. The small win turned out to be (for me) quite big in PLN, but it’s better not to think what would happen if I lost. Fortunately, the colleagues I had been waiting for had already arrived. I apologized and walked away from the table without risking any further play.

Apparently, playing cards was one of the ways of recruiting UB collaborators. Some were encouraged by high wins, others were losing and were offered to “play back”. Luckily, I was too busy studying and helping with motoring events that I didn’t get the chance to enjoy the club’s entertainment activities.

In the second half of the 1930s, big name-day parties and social gatherings at my parents’ home were becoming less and less numerous. Friends and relatives slowly crumbled or became less and less mobile. The crisis, the effects of which were clearly noticeable, was also not without significance.

It happened more than once that there was not enough cash at home. Of course, it was hard to talk about poverty. There was Mom’s jewelry, securities, good paintings, but there were also temporary problems with cash for current expenses.

In the last years before the war, parties became less and less frequent. Finally, although the financial situation definitely improved, it ended completely. It does not mean that there were no guests at our place, my parents ran an open house and many people came, my sister Danusia’s friends, later mine, but these were no longer big parties.

I liked and admired him (a historical name and a similar one from the same line as Kozietulski from Samossierra!). However, I could not bring myself to a longer conversation with him, going beyond the minimum requirements of good manners and hospitality. I don’t know where he lived, what he made of it, how he was getting along. I remember that he was always very neatly dressed in a tweed jacket, well pressed pants, a nice tie.

Janek survived the occupation. After the war – as a good old man – he married a lady whom I had probably met twice in my life at my aunt Rzewnicka’s (mother’s sister). I can’t remember her name. I only know that it was one of those “good” landowner surnames (I think Skarbek?). She was slightly younger than Janek and was his physical opposite. She had a fairly low, energetic voice and an equally energetic way of moving.

I think I found obituaries of both of them in the newspaper in the late 1960s. As I found out later in a very roundabout way, they committed suicide out of poverty; they had nothing to live on. I feel guilty that I didn’t get any closer to them. My mother liked Janek very much.

Our regular guest was engineer Stanisław Krupiński, technical director of the Haberbusch brewery in Warsaw. I liked him very much, he impressed me as a machine-savvy man and let me get bored on technical topics. He was coming with his wife; they had no children. My father knew him from childhood, because his father was an administrator (or maybe he performed some other function) in one of the farms belonging to the grandparents’ estate – Morawica.

The engineer Krupiński also knew my mother from her hen days. Apparently he was in love with Mama. I don’t know why he got trash. In any case, he became a true friend of the house. Both his parents liked and appreciated him very much.

Until his wife died (she died shortly before the war), we often visited them. They lived at Żurawia Street near Marszałkowska, in an outbuilding, on the ground floor. This house survived the Uprising and is still standing today.

There were many interesting – for me – things to look at: compasses, slide rule, calculator, technical books. Mrs. Krupińska made good cookies and preserves, and played the piano with pleasure. After his wife’s death, his niece, who ran his farm, moved in with him. We were there a few more times, but it was not the same Mr. Krupiński and not the same house. During the war, when I started my studies at the Wawelberg school, he gave me a slide rule. He served me faithfully until the Uprising.

I saw this niece – I do not remember her surname, not even her first name – once after the war in Krakow, in 1945 or 46. I don’t know how she found me and gave me the address. I know that I saw her and that Mr. Krupiński was not present during the conversation. Or maybe he just left somewhere, or maybe he was already dead. Unfortunately, I don’t remember.

Mother’s relatives, the Śliwiński family, also visited us. My father did not like them very much, because Artur Śliwiński was a senator, which, according to my father, almost ruled out him being a decent man. I don’t remember them well, but it seemed to me that they were just “normal”. On the other hand, I was very fond of visiting my old grandmother Śliwińska, who lived on Miedziana Street. Grandma (great-aunt) was very old and nice, but most of all at home there was a huge “Szlem” pointer, who once in his youth pulled a dish with roast from the table and was really ashamed to recall this prank: he would tuck his tail under him and squeeze into the corner behind the couch, from where it was difficult to pull out.

Father’s friend, judge (or maybe a prosecutor?), Stypułkowski, visited us. He was married to a Russian woman he met during his forced stay in Russia during the First World War. I think my parents knew them from those times. They lived in Żoliborz in a villa on Felińskiego Street, on the corner of Niegolewskiego (there is now a pharmacy downstairs). Mr. Stypułkowski found himself in England during the war and probably did not return to Poland after the war.

From time to time, always unexpectedly, my mother’s cousin, Gralewska, who lives in Łódź, would visit us. Her husband was a professional officer with the rank of a captain, which impressed me wildly. They had a son much older than me. I remember that he finished a technical college and there were problems with finding a job for him. He got it – my father, who knew “all of Warsaw”, helped him – in electrifying the Warsaw railway junction. Later he lost my sight completely. Old Gralewski died one or two years before the war. Aunt Gralewska came to us many times; I think she was once during the war. I don’t know what happened to her after that.

Mrs. Zofia

Every few months, always unexpectedly, Mrs. Zofia came to us. She was my sister’s tutor during the First World War and probably in the first post-war years, and then she looked after me until I was four or five. She was with my parents during the war in Russia, they survived the revolution there and returned to Poland together. She was very close to our family, treated like someone very close. She was an old maid with a very nice appearance, intelligent, well-read, from a “good family”.

Unfortunately, I do not remember her surname, because at home she was referred to as “Mrs. Zofia”.

She always worked in wealthy homes as a tutor. I liked her unexpected visits very much. I could always count on a small gift and sweets. She brought a lot of movement to our home, she told fascinating stories. If she found Mom doing the housework, she immediately helped to clean, sew, etc. She had a lot of ideas and her visit ended with rearranging furniture, hanging pictures, or completely changing the concept of a sweater that Mom was knitting.

I cannot imagine that anybody else could make such suggestions or comments to Mama. Mrs. Zofia was allowed to do anything. After she left her mother teased a little about her excess energy and fantasies, but almost always followed her advice. Sometimes, just to maintain her prestige, she claimed that she had had such an intention for a long time, but that she could not get together to implement it. So it’s good that Mrs. Zofia encouraged her.

One of the many visits of Mrs. Zofia was especially stuck in my memory because of the gift I received from her then. It was a penny celluloid toy in the form of a small circle. There was a growling whistle blowing into the mouthpiece connected to it, and a tiny celluloid toy car circled at high speed inside the circle.

None of my peers had such a toy. And no wonder. She came from Constantinople. Mrs. Zofia was there with her current employers during the holidays. Turkey was at that time a country so exotic that none of our close and distant acquaintances had ever been there – apart from, of course, Uncle Tadeusz, the enfant terrible of our family; but that is quite a different story.

About two years before the war, Zofia paid us another unexpected visit. She hugged me as usual, but from the very first moment I felt that something had changed. It was supposed to be the same as always, but still different. After a while, Mom and Father entered the room and Mrs. Zofia solemnly declared: I got married a month ago. We were all dumbfounded, no one could have imagined her as a married woman. It seemed to me then that she was already an old lady. Today I estimate that she was just over forty then.

I do not remember who her chosen one was, what his name was and what he did. Besides, she never introduced him to us. She was with us a few more times during the occupation. Always alone, without a husband. Seemingly as energetic and cordial as before, and yet a bit alien. At least we all thought so.

Mother Niekraszow’s cousin rarely visited us. She lived constantly in the provinces – somewhere in the Vilnius region, she spoke with a slight, singing borderland accent. In terms of beauty and clothing, she was a classic lady from a borderland manor, but I do not remember what she did. She always came to Warsaw on official matters. It didn’t interest me much then. She came by to “take a break from those horrible bureaucrats”. I liked listening to her stories about life in a remote province. They were fascinating and a bit exotic stories for me. I think she was with us at the beginning of the occupation. However, I am not sure about it. So many different people passed through our house at that time.

Danusia’s friends

Of my sister Danuta’s friends (8 years older than me), I remember best Zosia Keilówna. Best because she was a frequent guest with us, and also because of her extraordinary temperament. Danusia attended the gymnasium. Maria Konopnicka, which was located at Barbara Street. It was one of the best state female gymnasiums, although not as exclusive as Królowej Jadwigi, or private – Wazówna.

Apart from Zosia, we often visited Hanka (?) Klikunas, a Lithuanian native, who lives nearby on Piwna Street in the second or third house from Plac Zamkowy; Irka Emmel of the classic beauty of a German woman who tragically died during the occupation. Her family was of German nationality. Irka did not want to reveal either side. She came to Danusia to cry and ask for advice. I remember her, at the beginning of the occupation, leaving us several times with her eyes swollen from crying. Soon she suddenly stopped coming. As it turned out much later, her fiancé, who turned out to be an SS man, shot her.

I still remember the names of Sturm de Strem and Szokalska. The first one, probably because of its unusual sound. At the beginning of the 1930s, I knew almost all the names of Danusia’s friends. Not much has survived in my memory to this day. Danusia passed her secondary school-leaving examination in 1933. I am writing this fragment of my memoirs in 1994, i.e. after 61 years. I myself am surprised that I have managed to remember so many different details.

Junior high school Konopnicka – like the majority of middle schools in Warsaw – had the so-called a school estate, i.e. a kind of holiday home, to which all classes went one by one during the school year for weekly stays. Half the day was devoted to lessons, a different subject every day; in the second half, there were sports and cultural activities. The estate was located near Otwock.

A year or two before her final exams, Danusia returned to Warsaw on foot, of course with Zosia Keilówna, after the end of her stay – it was the result of the bet. My mother was outraged by this feat: a maid from a good home made a walk of more than 25 kilometers just because it was a bet. It was definitely the idea of this crazy Zośka.

Zosia had an established and well-established opinion in our house that she had crazy ideas and that you never know what comes to her mind. Her parents liked her, however, and she escaped her antics that, in the case of someone else, would have resulted in an absolute ban on entering our home.

In the final year class (or maybe it was a year earlier), the stay ended with a cabaret program, prepared and performed by the students. Apparently he was perfect. The witty and up-to-date texts for popular hits made a real sensation. I’m not sure about it, but it seems to me that this performance “on demand” was repeated in the school for parents and the teaching body.

My father had an excellent voice (baritone) – during his student years he sang in the university choir in Dorpat, and later in Warsaw in “Lutnia”. In approaching good humor, when he was alone at home (or he thought he was alone) he liked to walk around the apartment and sing his favorite arias and songs. One day I was surprised to find that he was singing couplets from Danusia’s school cabaret. I remember the first words sung to the melody of barcarolla:

“A poor poet is waiting by the window

Will the yellow blinds not rise?”

It was an allusion to an authentic, romantic story. The students in the school housing estate were carefully guarded. One of them was visited by her sweetheart and a whole conspiracy was drawn up so that she could go out to him. The agreed signal was to raise the yellow roller blind in the window. From another text sung to the melody of the hit song “When I Close My Eyes I See You Close” I remember the two opening stanzas:

“When I close my eyes I see two close,

When I close my eyes I see her a step away.

And like a sudden algebra test, the Terrible Two phenomenon

you burn my eyesight.

When I close my eyes I dream about the exercise again

and I think that the professor will give at least three;

But when I open my eyes, my dreams are over.

Unfortunately, I see two in the notebook. ”

And the first four poems of the song to the tune of “Titina ah Titina …”

“Latin ah Latin

This is a terrible hour,

These torments are Tantalus

These wars of Hannibal.”

________________________________________

A row in the theater

It happened in the last days of June or in the first – July. My father invited me to go with him to the Cyrulik cabaret theater on Kredytowa Street. At that time (1939), a cabaret student, it was almost a crime. My father said briefly, seeing Mom’s surprise and mine, no less: “I’ve seen this show, there’s nothing there that a sixteen-year-old high school student couldn’t see.”

Here I owe an explanation. My father was also a doctor of Warsaw theaters. At that time, not all actors were insured and could use the “sickness fund”. So they organized their own health service. Many famous doctors adapted to it, who gave them medical advice if necessary. It was an almost honorary job, as the fees for advice were rather symbolic. However, it was good to be a theater doctor.

The duties of a theater doctor became burdensome when a play was successful, it was played for a long time, and it was necessary to attend it a second, or even a third time. In such a situation, my father phoned his colleagues one by one, and finally found someone who had not seen the performance yet and had the time and the desire to see it. The theater doctor was obliged to provide a replacement when he could not (or did not want) to be present on duty himself.

This time, attempts to find a replacement failed. Father’s friends have either already seen this program or have gone on vacation. So Dad had to go to Cyrulik a second time for the same performance. My mother couldn’t, or maybe didn’t want to, watch the same show again, so my father suggested it to me.

I stuck into a new (a gift for the so-called “low matura”) suit made of brown Leszczkow wool, I put on a white shirt, an elegant tie and we went to the Kredytowa street to Cyrulik. Of course, we went in a horse-drawn carriage. The father of the cab only recognized when he was in a hurry or when the weather was bad. The evening was beautiful and warm that day.

Lekarz miał obowiązek być w teatrze na 15 minut przed rozpoczęciem przedstawienia. Weszliśmy więc do prawie pustej sali. Pracownicy teatru kłaniali się memu Ojcu. Widać było, że znali go od dawna.

The room began to fill up. Of course, my father met friends and got into a conversation with them. I discovered interesting photos on the walls of the foyer and started looking at them with interest. Immediately, however, the bell rang calling the audience to the hall, then another one urging them on, and the performance began. Contrary to Mom’s fears, the show did not actually contain “things” that a sixteen-year-old high school student couldn’t watch. Political topics prevailed. The program matched the general mood. Nevertheless, there were some nice songs, funny sketches. There were also dancing girls, but they were much less undressed than in the photos I just started watching before the show.

During the break, some friends approached my father. I was introduced to them. I was completely uninterested in the conversation, so I politely apologized to the company and on the pretext that I had to drink lemonade at the buffet, went to finish looking at the photos. After a while I heard a familiar voice “what are you doing here ?!” It was the director of the gymnasium (and high school) for them. Czacki – Sopoćko. He put his hand on my shoulder as if he had arrested a long-wanted criminal and boomed again “where have you come?” At first I was stunned, because I could expect anything, but not the director, who was famous for his austerity and military manners – he was a staunch legionnaire.

Apart from school celebrations, we saw him only in situations where he most often acted as a prosecutor and a strict judge at the same time. After a while I calmed down and calmly replied that I was here with the Father.

“Łżesz, no decent father would bring his underage son here!”.

This cry was heard by my Father just coming. Dad didn’t like legionnaires. He was also not a supporter of Piłsudski, although he respected him; while the legionnaires he considered careerists with few exceptions. My father, suppressing his rage, confirmed that I was with him and added that he had already seen the show and believed that there is no reason why I should not be able to see it.

“It’s not just about the program, it’s about where your son is. Please get him out of here immediately.

“The son will stay until the end of the show, because I am on duty here and I cannot leave, and at this time the son will not be returning home alone; moreover, I see no reason why he should not see the second part of the show. In my opinion, it is even better than the first. ”

“The school’s office is closed during the summer holidays. So please report at the beginning of the school year and collect your son’s papers. I will not keep such a student in a decent state school. ”

At this point, the bell for the end of the break rang. I heard: “We are going back to our seats, the second part is perfect, you’ll see for yourself in a moment.” The program was very good indeed, but my mood was already spoiled. I didn’t feel like changing schools again. Probably it was possible to act “from the top” and explain to director Sopoćko to ease the matter. But I wouldn’t have had an easy life in his school anymore. So my humor was spoiled. I also came to the conclusion that Father, however, rightly does not like legionnaires.

The problem was solved by the war. The school year did not start in early September; the school building at Kapucyńska Street was burnt down during the siege of Warsaw. For a short period of resuming secondary education, we had lessons in the school building (whose name I do not remember anymore) on Mazowiecka Street. I had doubts whether I could go to lessons, after all I was “fired”. Nobody, however, dealt with such details.

After the closing of secondary schools by the occupier after a dozen or so days, the so-called kits, that is, secret teaching in private apartments, in small groups of students. I lived very close to the old school. We had a large apartment; the rooms were huge. So the living room or dining room began to serve as classrooms.

Principal Sopoćko did not teach in our class. One day, however, he was replacing the sick or absent history teacher and he came to us for a lesson. It so happened that the door was opened by his Father. He pretended that he did not recognize him and, after exchanging the agreed recognition slogans, said with a serious face that the lesson could not take place. “For what, are we in any danger here?” the headmaster became concerned.

“Probably not; I didn’t notice anything suspicious. But you know, my son was fired during the holidays from school, so I will have to look for other sets for him, and let them have a flat. ”

“But doctor, who would deal with such matters today. I’m sorry if I got up. There is nothing to talk about ”

The history lesson went smoothly. We found that “terrible” Sopoćko in cozy conditions is quite nice and knows how to lecture in an interesting and unconventional way.

Over dinner that day, we talked about completing studies; Mom reminded that during the Russian partition she also studied Polish history and literature in private classes and that this education was also forbidden.

My father summed up briefly “that Sopoćko, although a legionnaire, but quite a reasonable man.”

More than once, in a good mood, he reminded me that had it not been for the war, it is not known whether I would have finished school.

MB

(excerpts from MEMORIES FROM THE PRE-WAR, WAR AND THE FIRST POST-WAR YEARS)