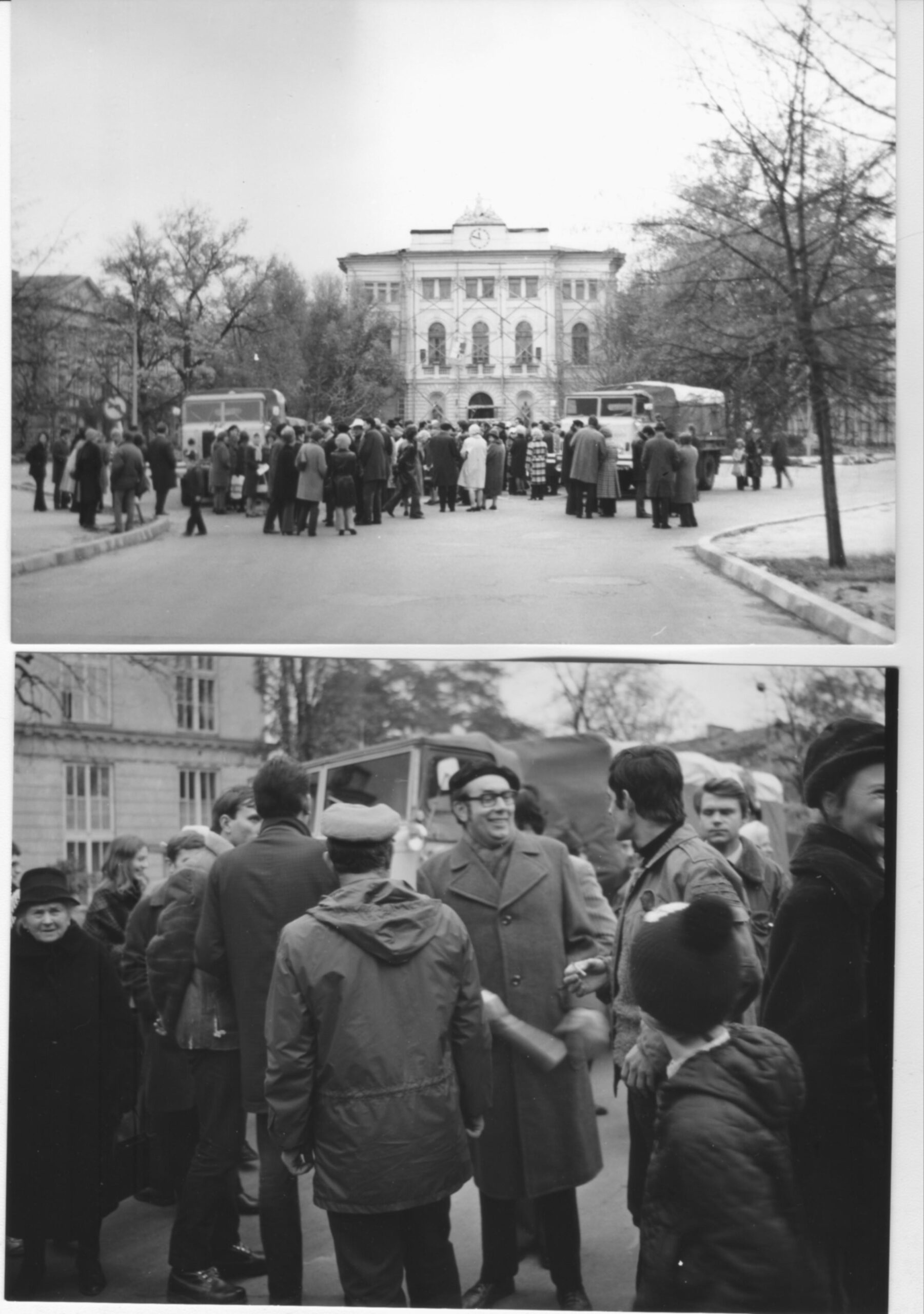

Świat Rodziny Podróżników – Wyprawy AWA 1972 – Refleksje o powstawaniu i odchodzeniu… AKADEMICKIE WYPRAWY AFRYKAŃSKIE – UNIWERSYTET WARSZAWSKI – pierwsza wyprawa rok 1972 + Wspomnienie o Wojtku Gajowniczku ,,Gajowym”

AWA – AKADADEMICKIE WYPRAWY AFRYKAŃSKIE – UNIWERSYTET WARSZAWSKI

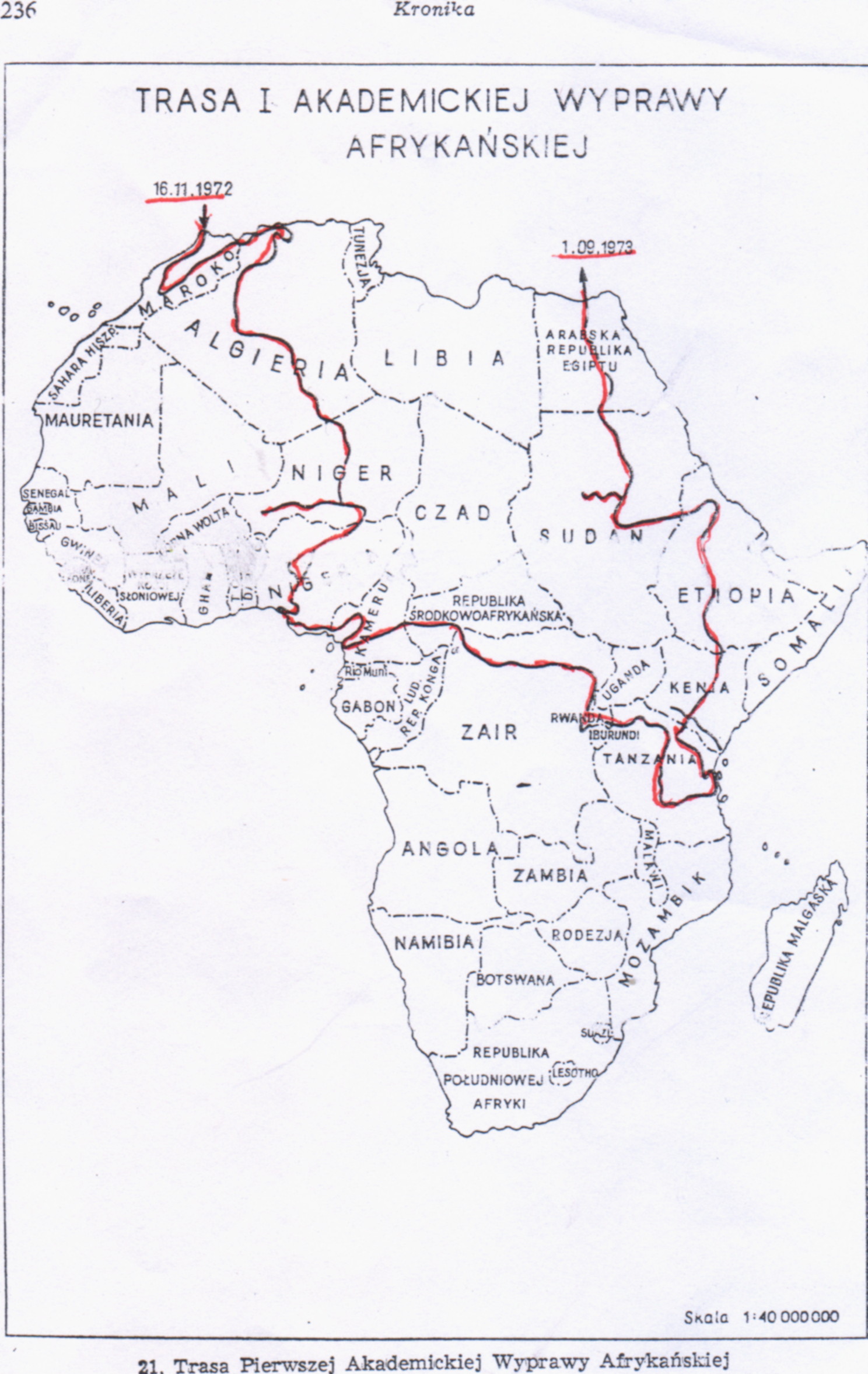

W dekadzie lat 1970-ych miał miejsce w Polsce „wysyp” naukowych wypraw do Afryki. Zrealizowano ich wówczas co najmniej kilkanaście. Oto wspomnienie dotyczące wyprawy pierwszej z 1972 roku

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

AWA UW ROK 1972

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

IN MEMORIAM – WOJCIECH GAJOWNICZEK by Wojciech Dabrowski, Sydney

Poniższy tekst, poświęcony pamięci Wojtka Gajowniczka (vel Gajowego), składa się z dwóch części.

Jedna, Pierwsza Część, (Part One), traktuje o naszych przygotowywaniach do Wyprawy, AWA72.

Druga część, (Part Two) opowiada o Wojtku , jakim Go pamiętam ze wspólnej podroży po Afryce.

Część Pierwsza, jest moją relacją z okresu przygotowań przed wyjazdem, w których Wojtek nie uczestniczył. Przekazałem ja Wojtkowi , ustnie, podczas kilku wieczorów , przy ognisku w Afryce. Wówczas też nagrałem swoją wypowiedź na magnetofonie. Przedstawiona poniżej pisemna wersja jest transkrypcją tego nagrania, do którego powróciłem po 50 latach, na wieść o Wojtka śmierci.

Tak powstał, z niewielkimi edytorskimi poprawkami, poniżej prezentowany tekst, zatytułowany Gajowniczek Part One i Part Two.

Wstęp i wprowadzenie

I.

Przez ostatnie 50 lat, od zakończenia AWA72, zaprezentowano polskiej publiczności kilka artykułów, wystawę fotograficzną i parę dokumentalnych “etiud” Jacka Olędzkiego. O ile mi wiadomo, nie napisano nic o genezie pomysłu zorganizowania “wyprawy” do Afryki i wytrwałych wysiłkach niewielkiej grupy entuzjastów, aby ten pomysł urzeczywistnić. Nic też nie powiedziano o osobistych dramatach towarzyszących temu projektowi.

II.

Niedługo przed naszym wyjazdem do Afryki, do naszej grupy dołączył Wojtek, jako doktor Wyprawy. Nie zdawał sobie sprawy z tego, ile pracy i optymizmu włożono w organizację AWA72, jak nazwaliśmy nasz projekt wyprawy studenckiej.

Na jego prośbę opowiedziałem mu o szczegółach wysiłku organizacyjnego wplatając w opowiadania krótki opis krajowego i międzynarodowego tła, którym cały projekt był przesiąknięty. Większość sytuacji politycznej, o której mówiłem, Wojtek znal z własnego doświadczenia. Zachęcał mnie jednak wtedy w Afryce, abym powracał do politycznych realiów w celu lepszego zrozumienia dynamiki tamtych czasów.

III.

Reasumując, traktująca o przygotowaniach Część 1 (Part one), mogłaby nosić tytuł “Wyboista droga do wyimaginowanej Afryki”. Jest to moja relacja z okresu przygotowań do wyjazdu, w których Wojtek nie uczestniczył. W pierwotnej formie relacja ta była wielogodzinnym przekazem, przy ognisku podczas naszych biwaków w Afryce. Część z tych rozmów nagrałem na taśmie magnetofonowej. Resztę odtworzyłem z pamięci, notatek i listów słanych do przyjaciół w Polsce.

Na wieść o śmierci Wojtka sięgnąłem do swego archiwum. Tak powstał ten tekst zatytułowany Gajowniczek, Part One (Część 1) and Gajowniczek Part Two (Część 2).

Część 2 (Part Two) opowiada o Wojtku jak Go pamiętam z Afryki.. Mógłby nosić tytuł Wojtek Gajowniczek, tak jak go zapamiętałem z Afryki.

Dotyczy Wojtka i jego wkładu w „ducha” AWA72. Wkład ten polegał na jego interwencjach medycznych, które wraz z jego specyficznym językiem i poczuciem humoru, nadawały “smak” i koloryt całej Wyprawie.

IVa.

Wojtka interwencje medyczne są przedstawione w porządku chronologicznym, zaczynając od zszywania czoła Michała pierwszego dnia w Afryce, a kończąc na pielęgnowaniu mnie w szpitalu Moshi, po incydencie na Kilimandżaro.

IVb.

Innym sposobem przedstawienia jego obecności na Wyprawie była wyrywkowa prezentacja jego powiedzonek i humoru. Różne słowne wtrącenia, sytuacyjne żarty, sprośne piosenki, które śpiewał z wielką pasją ( szczególnie po winie), budowały obraz osobowości Wojtka. Wpisywały się również w nastrój Ekspedycji jako całości.

Te mini epizody prezentujące Gajowego w Afryce, były niczym kropki na obrazach impresjonistów, stanowiące rozpoznawalne kształty tylko wtedy, gdy patrzy się na nie z daleka.

IVc.

Obraz, który wyraźnie wyłania się z “kropek” w przypadku Wojtka, pokazuje młodego, energicznego i ekstrawertycznego mężczyznę.

Wojtek, mówiąc wprost, był zarówno doborowym kompanem we wspólnej podroży jak i dobrym lekarzem.

A po Wyprawie stal się moim długoletnim przyjacielem.

V.

Niedawna wiadomość o śmierci Wojtka wstrząsnęła mną.

To dało mi impuls potrzebny do napisania o Jego życiu, jakie znam.

Część 1 powstała jako „produkt uboczny” mojej relacji o Wojtku z Afryki, a jej detaliczny charakter uzupełnia inne relacje, przesiąknięte chęcią zmitologizowania dokonań tamtych czasów, jakie z pewnością krążą w środowisku afrykanistów.

Tak powstała relacja ma charakter dokumentu historycznego, który odnosi się zarówno do naszych organizacyjnych poczynań, jak i do warunków, politycznych i kulturowych, w jakich te poczynania występowały.

VI.

Początek części 1 (Part one)

Nasza inicjatywa nie odbyła się w krajowej i międzynarodowej próżni.

Poniżej znajduje się kilka głównych punktów tła międzynarodowego, które należało wziąć pod uwagę, analizując samą możliwość AWA72.

Polska rzeczywistość, w której przyszło nam żyć, była bezpośrednią konsekwencją zmian rządowych na początku lat 70-tych (piszę o tym obszernie poniżej). Dało nam to szansę na wymyślenie studenckiej wyprawy do Afryki i zdobycie rządowych grantów.

VII.

Te dotacje na spektakularne projekty (jak nasze podróże czy wyprawy alpinistyczne) były “dojrzałymi do wzięcia”, oddolnymi inicjatywami. W zamyśle nowej ekipy Gierka miały reprezentować wiatr zmian i prezentować nowe oblicze polskiego ustroju, zarówno na użytek wewnętrzny, jak i zewnętrzny. Byliśmy prekursorami wyjazdów do Afryki jako dobrego tematu do wspierania. Wykonaliśmy kawał dobrej roboty z korzyścią zarówno dla nas, jak i dla władz. W ślad za naszym sukcesem poszło kilka innych “wypraw” bazujących na naszym doświadczeniu. To było tak jakby “niewidzialny głos” wołał: “zagraj to jeszcze raz, Sam”.

VIII.

To, co wydawało nam się “wyważaniem dopiero co uchylanych drzwi”, było zaproszeniem rządu do podjęcia takich działań, które stawiały nowe władze w dobrym świetle. Perspektywa zaistnienia w świecie młodej grupy podróżujących po Afryce na równi z zachodnimi rówieśnikami łechtała polska dumę patriotyczna.

Choć dobrze wyczuwaliśmy nowy trend w polityce, ale jeszcze nie byliśmy pewni na ile ten trend jest nam sprzyjający. Stopniowo zaczęło być jasne, ze nastały czasy rzadko występującej symbiozy między obywatelami a polityczna władza. . To było novum w autorytarnej polityce, w której byliśmy wychowywani.

IX.

Z perspektywy czasu wygląda na to, że to “czasy” szukające spektakularnych gestów otwarcia zaprosiły taką inicjatywę jak nasza. Mówi się w języku angielskim, ze czasami „temat poszukuje autora”. Nie było tak, jak myśleliśmy, że to my skłoniliśmy rząd do sfinansowania wyjazdu do Afryki. Rząd szukał okazji do sfinansowania spektakularnego projektu, aby poprawić swój wizerunek w społeczeństwie. Pojawiliśmy się w odpowiednim momencie z naszymi prośbami o wsparcie wyprawy do Afryki. Wzięlibyśmy na siebie wszystkie niebezpieczeństwa związane z tym przedsięwzięciem, a rząd zapewniłby odpowiednie środki finansowe. Podzielimy się łupami sukcesu między sobą.

X.

Pisząc różne petycje do instytucji rządowych o pieniądze lub inne wsparcie, spotkałyśmy się z wszechobecnym poparciem dla naszej inicjatywy. Czuło się, że my, mała grupa zapaleńców, właściwie wyczuliśmy Zeitgeist nastrojów politycznych. Proponując podróż do Afryki, wpisaliśmy się w rządową chęć otwarcia Polski na świat.

Wyczuwało się atmosferę patriotyczno-nacjonalistyczną na wszystkich szczeblach władzy. Popularne było hasło, że „Polak potrafi”. I skoro młodzież krajów Zachodu może swobodnie podróżować to dlaczego byśmy tak samo (lub lepiej ) nie mogli tego tez robić.

To był oczywiście utopijny sentyment.

XI.

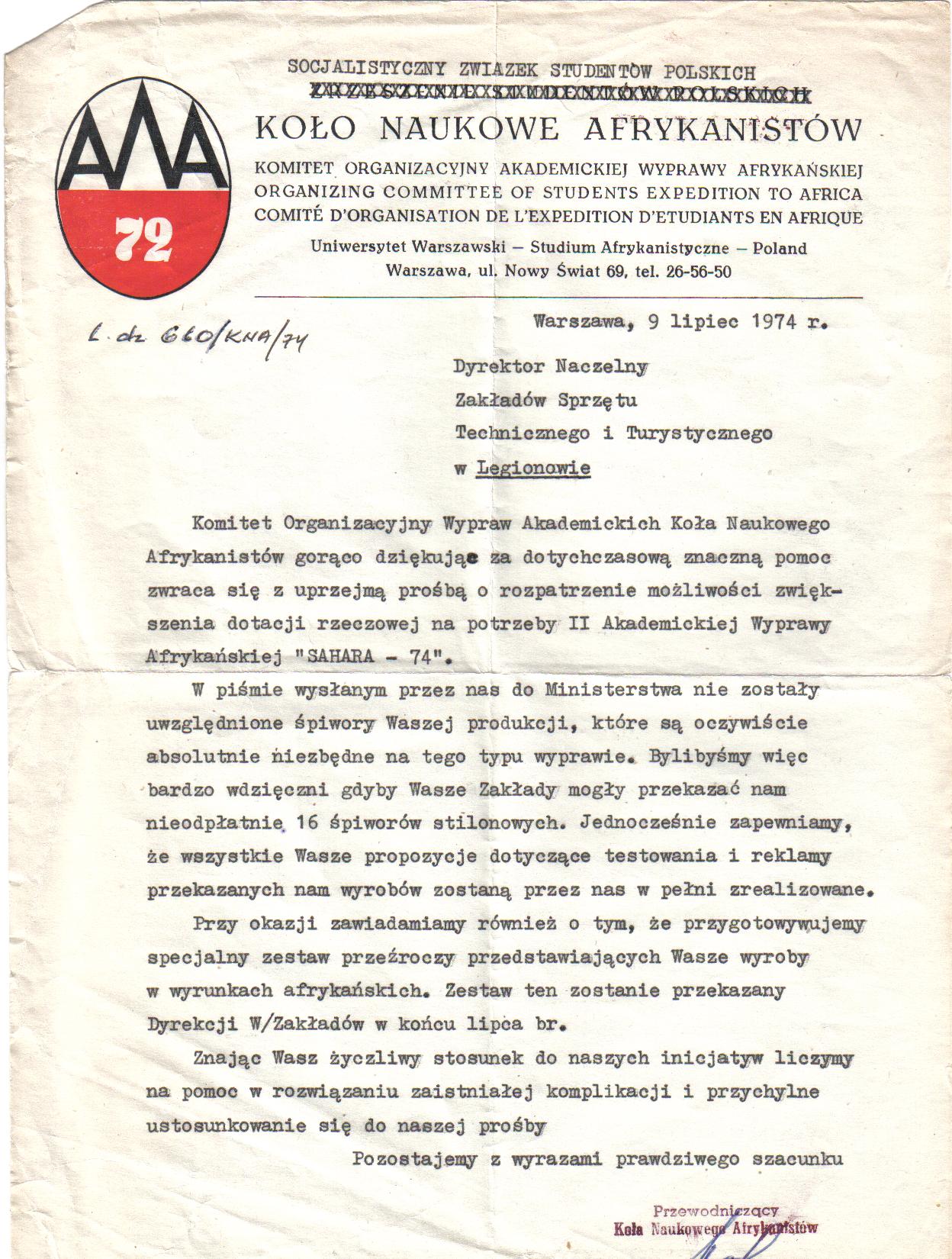

Byliśmy wspierani przez państwowe zakłady produkcyjne w formie bezpłatnych darów. Byliśmy wyposażeni w sprzęt kuchenny, konserwy, sprzęt elektroniczny. Mieliśmy radiostację do porozumiewania się między samochodami. Dostaliśmy nawet garnitury i koszule uszyte na wymiar. I to wszystko bez „skromnej prośby” przeslania im pocztówki z Afryki.

XII.

Niektórzy twierdzili (na przykład Ryszard Kapuściński), że takie bratanie się Partii z Narodem i zabieganie o wspomaganie, źle wróży tym pierwszym. No i wykrakał. Komunizm w Polsce upadł niecałe dwie dekady później. Ale wtedy, we wczesnym okresie tego „bratania” myśleliśmy tylko o tym jak wykorzystać nowe wiatry historii do swoich pro afrykańskich celów.

XIII.

Moc niespełnionych marzeń o przygodach i barwnym życiu, przydawała nam energii, dzięki której projekt stał się wykonalny. Flora, fauna i życie mieszkańców jawiła nam się w kolorowych barwach niczym sceny z obrazów Rousseau, który nigdy nie wyjeżdżał z Francji i przeto jego tęsknota za egzotycznym światem była potęgowana nieskrępowaną wyobraźnią.

Pomimo otwierania się nowych możliwości, nikt nam tak śmiałego projektu jak wyprawa akademicka do Afryki, nie podawał na tacy. Było wiele innych podań o finansowe wsparcie.

XIX.

Musieliśmy wiec określić się w formie zrozumiałej dla finansowych decydentów. Wchodziły w grę dwie możliwości. Mogliśmy przedstawić się jako uczestnicy ambitnego wyczynu sportowego typu rajd po Saharze. Albo przedstawić projekt jako przedsięwzięcie naukowe. W pierwszej wersji wchodzilibyśmy we współpracę z Ministerstwem Sportu i Turystyki. W drugiej wersji wpisywaliśmy się w kuratele UW.

W początkowej fazie przygotowań skłanialiśmy się (naiwnie) ku tej pierwszej identyfikacji. W dalszej fazie przygotowań skłanialiśmy się (również naiwnie) ku „naukowemu” charakterowi Wyprawy . Nie byliśmy przygotowani, pomimo ćwiczeń fizyczno-emocjonalnych mających nam służyć w tropikach, do jazdy na oślep, w dzień i w noc, przez Afrykę. To nie miałoby sensu.

O żadnej;” naukowej” wersji też nie mogło być mowy.

XX.

Byliśmy prekursorami nowego, ogólnonarodowego trendu otwarcia się Polski na świat. Stąd wsparcie ze strony wszelkiej maści producentów. Od przemysłu odzieżowego po konserwy, leki i gadżety elektroniczne. Byliśmy oczywiście nośnikami fantazji o wolności i odwagi, żywionych po cichu przez rzesze ludzi, uwikłanych w codzienne, przyziemne sprawy. To oni, wspierając nas na wiele sposobów poprzez darmowe przekazywanie nam swych produktów, czuli swój drobny udział w naszym planie stąpania wśród chmur.

Nawet, w swej skromności, nie proszono nas by w zamian przesłać im pocztówkę z Afryki.

XXI.

Nowa ekipa, pod przywództwem Edwarda Gierka, pożyczyła duże pieniądze od zachodnich banków, przeznaczane na rozwój przemysłu. Promowała też indywidualne wyjazdy do krajów, o których do niedawna można było tylko marzyc. Zapotrzebowanie na wyszkolonych specjalistów, którzy wchłonęliby nową technologię, wysłało tysiące młodych ludzi za granicę.

Szybko rozwijał się również sektor konsumencki.

XXII.

Innymi słowy, lata 60te i 70-te były burzliwym okresem nadziei na „lepszą” (cokolwiek miało by to znaczyć) przyszłość.

Na tę Przyszłość „obozy polityczne” pracowały rożnymi sposobami i kanałami.

Zademonstrowanie swej obecności w Afryce, choćby w tak nieznaczny sposób jak przejazd przez Kontynent wyprawy studenckiej, wpisywało się pozytywnie w plan rozpoznawalności polskiej flagi w krajach świeżo zdobywających polityczna niezależność.

I myśmy byli beneficjentami tej wielokierunkowej strategii.

XXIII.

“Małe jest piękne” – to była dominująca mantra, zdobywająca popularność wśród młodych ludzi Zachodu, w każdym aspekcie życia. Prosta w swojej formie sztuka afrykańska została doceniona przez czołowych europejskich artystów.

Muzea gromadziły dzieła ludowej sztuki, „podziwiane” przez europejska publiczność.

XXIX.

Artefakty miały przekazywać „prawdę” o wartości “prymitywnego”, ale szczęśliwego życia, które można by naśladować w zachodnich metropoliach zmęczonych konsumeryzmem.

Podobne mrzonki o „szczęśliwym, choć ubogim życiu” leżały u podstaw projektu zbierania “artefaktów” przez studenckie ekspedycje.

XXX.

Dla zachodniej młodzieży podróżowanie było poszukiwaniem “prostoty” i radości życia, wolnego od biurokracji rozwiniętych krajów zachodnich. Wycieczki do Kapsztadu lub Singapuru były rytuałem “przejścia” z jednego stanu osobistego rozwoju, w następny. Używanie marihuany na dużą skalę było wymogiem tego etapu życia.

Sytuacja w Polsce była inna. Tu nie było przemęczenia konsumeryzmem. Podróże były przywilejem nielicznych, zaradnych młodych ludzi, a nie masowym aktem kulturowym.

XXXI.

Niezalenie od dobrej koniunktury, na która natrafiliśmy, musieliśmy swój projekt przekonywująco przedstawić finansowym decydentom. Nie byliśmy jedynymi starającymi się o pieniądze.

To prowadzi nas do kwestii tożsamości, którą musieliśmy rozwinąć, aby przedstawić nasze wnioski o sponsoring rządowy.

XXXII.

Uznaliśmy, że najlepiej będzie użyć określenia “ekstremalne wydarzenie sportowe”.

XXXIIa.

Inną możliwością była orientacja “naukowa”. Oba kryteria, sportowe i naukowe, miały poważanie w biurokratycznej administracji. Nie trzeba dodawać, że zachodni podróżnicy nie mieli problemów ze znalezieniem funduszy i odpowiedniej etykiety dla swoich wędrówek po świecie. Wystarczyły im niewielkie sumy własnych pieniędzy.

Chcieli poznać, tak zwane „kraje rozwijające się”, na poziomie życia codziennego ich mieszkańców. Po angielsku mówi się o kontaktach na „grass roots level”, czyli na najniższej warstwie społecznej, na poziomie „trawnika”. Młodzi, idealistycznie nastawieni ludzkie zachodu, chcieli spotykać się i bratać, kiedy tylko było to możliwe, z ubogimi mieszkańcami Afryki, Azji czy Ameryki Południowej.

XXXIII.

My nie mieliśmy takich „pro ludzkich” planów. Aby uzyskać fundusze musieliśmy się przedstawiać w kategoriach zrozumiałych i cenionych przez władze rządowe. Mogliśmy albo uprawiając widowiskowe sporty ekstremalne, w stylu rajdów ciężarówkami po pustyniach, albo “pięknie się prezentując” w trybie “szanujcie nas, zaściankowych Polaków”. Jeśli mieliśmy spotkać kogokolwiek z “miejscowych”, to miała to być kadra uniwersytecka. Na spędzenie czasu w towarzystwie miejscowych Afrykanów nie było ani czasu, ani ochoty, ani sponsoringu.

O „zaprzyjaźnianiu się” lub „wzajemnym poznaniu” nie mogło być mowy. Afrykę mieliśmy poznawać z wysokości szoferki sześciotonowych pojazdów. Mieliśmy, jak głosiła piosenka: „siedź jak w kinie/na dachu przy kominie/a może jeszcze wyżej niż ten dach, dach, dach”

Czuliśmy się uwikłani w różne kryzysy tożsamości.

XXXIX.

Z jednej strony przeszliśmy przez różne testy fizyczne i psychologiczne mające na celu udowodnienie naszych wysokich kwalifikacji do wyzwań ekstremalnie sportowych. Ćwiczyliśmy intensywny rozwój fizyczny oraz wschodnie praktyki kontroli umysłu i emocji.

Mniej, o ile w ogóle, uwagi poświęcono metodologii “badan naukowych”, którym mieliśmy się poświecić w Afryce.

XXXX.

Próba wymyślenia przez znawców Afryki, takich jak prof. Zajączkowski i Ryszard Kapuściński, wykonalnego planu dobrze dopasowanego do naszej konkretnej sytuacji, została przez nas zignorowana.

Częściowo z powodu braku mentalnej zdolności do zaangażowania się w jakiekolwiek poważne planowanie w nieznanym nam środowisku afrykańskim.

A częściowo dlatego, że w głębi serca nie wierzyliśmy, że z tego projektu może powstać jakakolwiek poważna praca o obiektywnej wartości lub osiągniecie sportowe światowej klasy.

XXXXI.

Wspominane w planach zadanie kolekcjonowania eksponatów muzealnych też nie budziło naszego entuzjazmu. Wielu z nas odwiedzało kiedyś Londyn czy Paryż i było świadome ilości tanich artefaktów wystawianych na sprzedaż na pchlich targach. Prawdopodobieństwo skolekcjonowania obiektów o muzealnej wartości, pozyskanych drogą wymiany drobnych elementów z naszego indywidualnego wyposażenia (jak koszulki, sandały, itp.), wydawało się mrzonka. A poza tym, ciągle podróżując, (niczym uciekając do przodu) mogliśmy tylko pozbierać drobne obiekty od sasa do lasa, bez żadnej wiedzy o ich rytualnej wartości..

XXXXII.

Zamiast poważnych przygotowań i dyskusji programowych przyjęliśmy, nieświadomie, ducha niefrasobliwego festiwalu, w stylu studenckich Juwenaliów.

Dominującą mantra było: co będzie to będzie!! Ważne, żeby było.

Naszej mentalnej niefrasobliwości można było przypisać hasło zapożyczone z kręgów kościelnych: Alleluja !!! i do przodu !!!!

XXXXIII.

Znaleźliśmy schronienie w nastroju studenckich bachanalii, swobodnego rozpasania, podważającego wartość ponurych nastrojów dotychczasowych haseł politycznych, głoszących rozmaite przewagi “ustroju socjalistycznego” nad kapitalistyczną dekadencją. Nikt z nas nie wierzył w wartość “robotniczo-chłopskiego”, proletariackiego projektu politycznego.

Nikt też tego też już oficjalnie nie głosił.

XXXXIV.

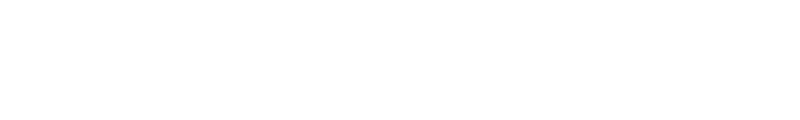

Na przykład, udział w pochodzie 1 Maja był, dość powszechnie, postrzegany jako środowiskowy „obciach”. A tak było pomimo tego, że świętowanie Międzynarodowego Dnia Pracy było uważane za obywatelski obowiązek sygnalizujący poparcie dla polskiego rządu Mnożyły się polityczne żarty podważające jakąkolwiek autorytet władzy państwowej. Jednak bardzo niewielu z nas, studentów, aktywnie zaangażowało się w polityczną kontestację. Zamiast tego woleliśmy bezpieczniejszą opcję uciekania się do “żartów”.

“Wydarzenia 1968 roku” jeszcze bardziej powiększyły przepaść między partią rządzącą a większością studentów. Ale ta „przepaść” nie wyrażała się w antyrządowych, studenckich demonstracjach lecz raczej poprzez wycofania wszelkiego poparcia i ucieczce w groteskę i niefrasobliwość.

Zmiana rządów u progu lat 70. dokonała się dzięki protestom stoczniowców i ich ofierze krwi, a nie mobilizacji młodej inteligencji.

Piszę o tym w dalszej części tej relacji..

XXXXV.

Ta “młodzieńcza”, otwarta i nie zaangażowana politycznie postawa była „twórcza” w tym sensie, że pozwoliła nam swobodnie poruszać się w obszarze do niedawna zupełnie nieznanym, niemalże wykraczającym poza wyobrażenia. Wkraczaliśmy w krainę spopularyzowana przez sztuki Sławomira Mrozka, Ionesco czy Witkiewicza, w której „wszytko jest możliwe”, niczym bieg wypadków w kolędzie bożonarodzeniowej.

Różne hasła polityczne pozostawiały nas całkowicie obojętnymi. Żaden z nas, organizatorów Wyprawy, nie należał do PZPR. W przeciwieństwie do członków PZPRu, z których wielu nastawionych było programowo na karierę zawodową, my, studenci Studium Afrykanistycznego, nie byliśmy karierą zainteresowani. Każdy z nas porzucał życie zawodowe dla perspektywy wyjazdu do Afryki. Po powrocie do domu nie czekała nas żadna nagroda w postaci atrakcyjnej pracy. Chyba, że ktoś byłby w stanie wykroić sobie jakąś przyszłość z afrykańskiego doświadczenia.

XXXXVI.

Kiedy wiatry historii zmieniły sytuację polityczną na naszą korzyść, Nikt z nas nie odczuwał wdzięczności za nowo rozdzieloną hojność. Zamiast tego dotacje rządowe finansujące różne inicjatywy oddolne, takie jak organizacja AWA72, były odczuwane jako “łupy wojenne”, prowadzone przez dziesięciolecia między obywatelami a partią.

Zaledwie dekadę później, na bazie protestu na gruncie ekonomicznym powstał masowy ruch Solidarności, który obalił komunizm. Elementem tej kontestacji był też zanik autorytetu Partii, która przetrwanie socjalizmu widziała w zmniejszeniu dystansu Rząd – Obywatele, poprzez popieranie różnych inicjatyw oddolnych. Jak choćby nasza wyprawa do Afryki.

XXXXVII.

Choć sympatie pro-partyjne prawie nie istniały, nikt z nas (oprócz kilku kolegów szczególnie silnie motywowanych moralnie) nie dystansował się tak silnie od ustroju, żeby odczuwać obiekcje przed występowaniem o dotacje finansowe, kiedy nadążyła się ku temu okazja.

Raczej dominowała ludowa mądrość nakazująca „branie co się nadarza” i „chodu w krzaki”.

Przypomina to znaną deklaracje Zsa Zsa Gabor, znanej artystki amerykańskiej z okresu zdominowanego przez Marylin Monroe, że nigdy nie nienawidziła mężczyzny na tyle, by po rozstaniu oddać mu diamenty, które od niego dostała.

XXXXVIII.

Atmosfera niefrasobliwej burleski docierała do studenckiego życia kulturowego i osobistego. Mnożyły się teatry studenckie wyśmiewające polityczna ortodoksje. Nazwiska twórców takich jak Hłasko, Osiecka, Marek Nowakowski czy Janusz Głowacki, autorów popularnych piosenek i utworów literackich ukazujących „dekadencje i wypalenie” życia „prostych ludzi”, były powszechnie znane i cenione za swój „autentyzm”. Alkohol lal się strumieniami. Teatry eksperymentalne Grotowskiego czy Kantora należały do naszego kanonu kulturowego. Jazz był ulubioną formą muzyczną.

XXXXIX.

Choć nominalnie „katolicy”, nasza przynależność do Kościoła była formalnością bez wpływu na postawy moralne. O ile wiem, nie kradliśmy, „czciliśmy ojca swego i matkę swoja”, „nie zabijaliśmy”, itp. Prawdopodobnie z unikaniem „cudzołóstwa”, w wolnej interpretacji tego nakazu, mogło bywać rożnie. Nie dyskutowaliśmy takich dylematów. Żyliśmy pogodnym, w miarę wygodnym, wystarczająco dostatnim życiem, spędzanym w towarzystwie przyjaciół obojga płci. Wszystkie szkoły, z pojedynczymi wyjątkami, były koedukacyjne. Wpływało to z pewnością na swobodną atmosferę w relacjach chłopców z dziewczętami. W weekendy chodziliśmy do teatrów lub na tańce do klubów studenckich. Czasem na występy kabaretowe. Darmowe wyższe studia były naturalną kontynuacją wcześniejszych form edukacyjnych. Przeważnie mieszkaliśmy w rodzinnym domu, bo na wynajmowanie pokoju wspólnie z kolegami, nie było nas stać. Koledzy spoza Warszawy mieszkali w akademikach studenckich po sześciu w jednym pokoju.

Młodzież warszawska (nie wiadomo, dlaczego) trzymała się razem, rzadko mieszając się z młodzieżą z prowincji.

Katolicyzm był symbolicznym, w wersji „lite”, wyrazem niezgody (tez w formie lite) na komunizm w Kraju. Każdy z nas prowadził bogate życie towarzysko-erotyczne, bez planów na „małą stabilizacje”.

Choć nie można było mówić o „rewolucji seksualnej” w wersji „zachodniej”, nie mniej nasza mentalność obyczajowa mogła być postrzegana w ostrym kontraście, do surowej obyczajowości i mentalności, większości, naszych rodziców. Tak jak hasła głoszące nakaz walki o sprawiedliwość społeczną nie robiły na nas wrażenia, tak i nawolywania (nieliczne) do praktykowania, na poziomie osobistym, wymagających wartości moralnych jak „bezgraniczna miłość”, „samopoświęcenie” czy bezwzględna lojalność, pozostawały bez oddźwięku niczym nakazy „nadstawiania drugiego policzka” lub „kochania bliźniego swego jak siebie samego”. Było to odejście od „zaangażowania społecznego”, które było autentyczną reakcją na nierówności i niesprawiedliwości okresu przedwojennego, leżącą u podstaw popierania ustroju „socjalistycznego” w Polsce przez wielu intelektualistów i artystów, kalibru filozofów Kołakowskiego czy Baumana.

My byliśmy już odległymi spadkobiercami „tamtego okresu”.

L.

Z pewnością, nasze postawy, były nieuświadamianą reakcją na nieudolne próby ze strony władz państwowych stworzenia, w początkowych okresach ustroju „socjalistycznego”, metodą nachalnej propagandy, „nowego jakościowo typu obywatela”, wrażliwego na los „narodów uciskanych” i eksploatowanej przez zachodni kapitalizm, „klasy robotniczej”. Myśmy tylko doświadczyli samego końca próby „radykalnej modyfikacji” ludzkiego zachowania zwanej w naukach politycznych „hard core social engineering” kontrastującej z polityką „soft core” socjaldemokratów na Zachodzie.

LI.

Jak mawiał Michał Olbiński, jeden z uczestników Wyprawy: „była zimna wódka, piękne dziewczyny, śledź w śmietanie; czyli było dobrze”. Jedynie co nas zaprzątało to to czy nasza dana sympatia: “kocha, lubi, szanuje, nie chce, nie dba, czy żartuje…”. O „ślubnym kobiercu”, o którym mowa w dalszej części tej wyliczanki, nikt z nas nie myślał.

„Katechizacja” prowadzona w pomieszczeniach przykościelnych była okazją do spotkań towarzyskich młodzieży z różnych szkół. Po godzinnej pogadance na tematy luźno związane z arkanami wiary, w sekcji „pytania i odpowiedzi” raczej prowokacyjnie niż dociekliwie, pytano prowadzącego zajęcia księdza profesora Józefa Gniewniaka, czy „calowanie się dziewczyn z chłopakami jest grzechem”.

Odpowiedz Józefa głęboko zapadła nam w serca.

Powiedział bez wahania, że calowanie to „NIE” grzech, ale rozpowiadanie o tym wydarzeniu wśród koleżeństwa, już „TAK”. Rozumieliśmy, że przechwałki na temat „sukcesów towarzysko/erotycznych” nie licują z honorem jaki każdy z nas powinien był mieć. Zachowanie, zwane po angielsku „kiss and tell”, jest krytyką kolizji obszaru intymnego, a przeto „świętego”, z obszarem publicznym, a przeto „świeckim” .

Przypuszczam, że tak jak dla mnie, takie pojęcie „grzechu” było przez nas zrozumiale i akceptowalne.

Ta powyższa dygresja została tu umieszczona w celu rzucenia światła na nasze charaktery w dobie poprzedzającej wyjazd do Afryki.

Nic dziwnego, że beztroski nastrój, opisany powyżej, przeniósł się również na afrykańskie podróże. AWA72 nie była ani naukowym, ani sportowym projektem, ale “juwenaliowym” przedsięwzięciem, który nie stronił od „zgrywu”, parodii z samego siebie choć był świadomy pewnych (nie ortodoksyjnych) limitów moralnych.

LII.

Poniżej wymieniam jeden z wielu przykładów „filuternej”, podszytej „zgrywem” postawy Wyprawy, która miała miejsce w pierwszych tygodniach podroży.

Podczas przejazdu przez północne Włochy zostaliśmy ugoszczeni przez komórkę Młodych Komunistów. Młodzi ludzie oczywiście potraktowali spotkanie bardzo poważnie.

Wygłosili kilka powitalnych przemówień i podali lekki posiłek z dobrym włoskim winem.

Pod wieczór ogłosiliśmy chęć obdarowania naszych gospodarzy prezentem “bardzo bliskim naszym sercom”. Lonek i Andrzej (kierowca) podarowali wielkie mosiężne popiersie Lenina, wśród naszych sarkastycznych uśmieszków i parodiujących entuzjazm, oklasków. Standardowe popiersie z lat 50-tych, od czasu “wycofania z użytku” i wyrzucane gdzieś do lamusa, zostało ustawione na stole prezydialnym, przed gospodarzami.

To była, niewątpliwie, żenująca i rażąca parodia. Nie wiadomo jednak czego. Przecież nie chcieliśmy obrażać naszych młodych gospodarzy. To był zgryw rodem ze studenckich bachanalii. Nikt z nas nie żywił dobrych uczuć do popiersia Lenina. Ten gest był sarkazmem skierowanym w stronę gościnnych, młodych gospodarzy i całej socjalistycznej scenie politycznej, którą nie tyle kontestowaliśmy, ile traktowaliśmy z pewnym politowaniem i trudną do zdefiniowanie, wyższością.

My byliśmy „oświeceni” (po protestach stoczniowców z grudnia 1970go) podczas gdy młodzi komuniści, tak jak politycy identyfikujący się koniunkturalnie z „socjalizmem”, pozostawali po mrocznej stronie społecznego podziału.

W owych czasach Lenin figurował jedynie w licznych dowcipach. Oferując to bezwartościowe dla nas popiersie, zdawaliśmy się mówić, ze jesteśmy o wiele bardziej rozwinięci ideologicznie niż gospodarze, wciąż przesiąknięci komunistycznym mambo-jambo.

LIIa.

Najprawdopodobniej, takie było znaczenie tej parodii zademonstrowanej przez Lonka, głównego wśród nas „zgrywusa”. Dowiedziałem się, że Eugeniusz nawet tego incydentu protokolarnego ,nie zauważył.

LIIb.

Późnym wieczorem, podczas zwiedzania słynnej katedry Mediolanu w towarzystwie młodych komunistów, jeden z nas przyjął komunię w sposób, który wyglądał na prowokacyjny, choć prawdopodobnie nie był zamierzony przez szczerego katolika.

LIII.

Ta obrazoburcza postawa swobody, graniczącej z anarchią dominowała całą Wyprawę. Raz z większym innym razem z mniejszym nasileniem. Wyczuwało się też krytycyzm pod naszym adresem ze strony Polonii zamieszkującej Afrykę, która wielokrotnie oferowała nam schronienie i gościnę. Stara prawda, że „krew nie woda” dawała, od czasu do czasu, o sobie znać zakłócając ustatkowane, rodzinne życie naszych gospodarzy.

LIIIa.

„Niedobra sława” ostrzegająca potencjalnych gospodarzy o naszym „nie eleganckim” zachowaniu, jakiego się czasem dopuszczamy, wyprzedzała nasz przejazd, dowodząc istnienia daleko rozwiniętej sieci kontaktów Polaków, rozsianych po całym Kontynencie.

Pomijając bezpodstawne oczekiwania co do „naukowego” charakteru, Wyprawa była wolna od ideologicznego, politycznego, czy filozoficznego, doktrynerstwa a nawet, wolna była od dyscypliny, jaka można by było oczekiwać po młodych „akademikach” o wysokiej kulturze osobistej. Brak tego na końcu wymienionego nakazu wstrzemięźliwości, można by, patrząc retrospektywnie, poddać krytyce.

LIV.

Pojęcie “liminalności”, to jest zawieszenia wysiłków intelektualnych, jakie można było przypisać Wyprawie, było „w gruncie rzeczy” postawą twórczą, otwartą i zdolną do improwizacji. Umożliwiało absorbowanie wszelkiego rodzaju nieoczekiwanych wydarzeń i podejmowania dobrych decyzji. Niewątpliwie, dzięki takiej postawie udało się przejść „suchą nogą”, przez wiele potencjalnych, większych lub mniejszych, katastrof.

LV.

Taka swobodna, wolna od dogmatyzmu postawa, choć nie „sprzedawała” się finansowym i akademickim decydentom, ani przed wyruszeniem ani nie po powrocie, była siłą Wyprawy. Dlatego do niej nie nawiązywano, przedstawiając Wyprawę, nieprawdziwie, jako sukces poznawczy. Podkreślano znaczenie zbiorów etnograficznych bez wiedzy o ich roli w lokalnych rytuałach, które, jak twierdzono, mogłyby zasilić kolekcje muzealne.

LVa.

Nic wiec dziwnego, że poważni akademicy jak Eugeniusz i Bogdan (dokooptowani do Wyprawy przedstawianej jako przedsięwzięcie o charakterze naukowym), czuli się wyraźnie wyalienowani z tej atmosfery, a nawet, pochodząc z „dobrych domów”, zaambarasowani naszym, co pewien czas się powtarzającym, zachowaniem, nie licującym z postawa młodej inteligencji polskiej.

Bogdan wycofał się z Wyprawy w połowie jej trwania. Eugeniusz, co najmniej raz, wspierany przez kierowców Staszka i Krzysztofa, usiłował Wyprawę przerwać i zakończyć. Najprawdopodobniej chciał w Kraju kontynuować pracę akademicką lub postawić na karierę dyplomatyczną. Tylko ostry sprzeciw ze strony pozostałych uczestników pokrzyżował ten plan.

LVI.

Powyżej przedstawiony rys dominującego stylu zachowania, zwanego przez Kunderę „nieznośną lekkością bytu”, wyjaśnia, przynajmniej częściowo, dlaczego, mając perspektywę wyjazdu do Afryki, mało kto z nas brał pod uwagę wpływ długotrwałej rozłąki na los głównego, w owym czasie, związku uczuciowego.

Afryka była najważniejsza !!! i taka hierarchia na liście wartości była, dla większości z nas, bezsporna.

LVII.

Nie znaczy to, że byliśmy „chłodni” w swych zaangażowanych. Będąc już w Afryce pisywaliśmy namiętne listy.

Śpiewaliśmy rzewne piosenki o bólach rozstania. Itp. To było jednak „słodkie cierpienie”, gdyż w głębi serca, każdy z nas czuł że, jak jest w popularnej piosence „…bo to męska rzecz być daleko, a kobieca wiernie czekać”.

Pewnie należałoby taka postawę nazwać „seksistowską” osadzoną w tradycjach patriarchalnych, ale w owych czasach rzadko kto ją krytykował.

LVIII.

Bonanza trwała sześć lat. W 1976 roku Polska ogłosiła bankructwo. W krótkim czasie „wiosny lat 70ch” podejmowano błędne inicjatywy gospodarcze na fali entuzjazmu przypominającego emocjonalną euforię. Dopiero po gospodarczej katastrofie przyszło przebudzenie i poszukiwanie winnych sprowadzenia Kraju na manowce.

LIX.

Wyprawy akademickie tego okresu nosiły wszystkie znamiona „wzmożenia” kulturowo/gospodarczego nie zważającego na koszty, cele i domniemane zyski ustanawianych inwestycji. Życie zrewidowało sentyment, że „chcieć to móc”. Był to sentyment wynikający z braku doświadczenia i szacunku dla pieniądza. Czyli cech mozolnie wypracowywanych z pokolenia na pokolenie w krajach historycznie kształtowanych przez projekt kolonizacji i prywatną działalność gospodarcza.

Wraz z upadkiem gospodarczym i entuzjazmem patriotycznym skończyły się marzenia o sponsorowanych podróżach po Afryce. Nastąpił czas rozliczeń z „błędnie rozpoznanych” inicjatyw inwestycyjnych, w „tamtym” okresie.

LX.

Wyprawy nie były jednak „bezwartościowe”, choć nie spełniały pokładanych w nich, nierealistycznych, nadziei. Wniosły wartość w życie uczestników, tj. tej garstki szczęśliwców, którzy zostali zakwalifikowani na wyjazd bez formalnej rekrutacji, legitymujący się jedynie sprawnością fizyczną i odpowiednim zdrowiem.

No i „sztuka” bycia w odpowiednim czasie w odpowiednim miejscu.

LXI.

Niektórzy z nas znaleźli podczas Wyprawy inspirację, która zdominowała ich przyszłość. Innymi słowy, doznali w Afryce “objawienia”, co zrobić konstruktywnego z resztą życia. Wśród nich ja znalazłem powołanie do antropologii.

W szczególności do studiowania tak zwanego “procesu chrystianizacji”. Początkowo planowałem wrócić do Afryki by pracować w misji jako woluntariusz uczestnicząco/obserwujący. Później zmieniłem plany na Papuę Nową Gwineę, gdzie spędziłem dwa lata badając ten temat.

Pobyt ten był podstawą uzyskania tytułu „doktora filozofii” na Narodowym Uniwersytecie w Canberrze (ANU).

LXII.

Po 50 latach można wreszcie przyznać, że AWA72 nie była ani “sportowym”, ani “naukowym”, ale wspaniałym i radosnym doświadczeniem dla większości z nas, prowadzonym głównie w formie bachanaliów.

W grupie nie było ani intensywnego sportu, ani zaangażowania “badawczego”, a każda próba nadania podróży “naukowego” wymiaru (przez Eugeniusza, Bogdana czy Andrzeja) była odbierana z lekceważącą ironią.

A wszystko zaczęło się jak to przedstawiam poniżej!!!

Koniec Wstępu.

—

—

2.GAJOWNICZEK CZ.2 KC MARZEC 22 SRODA

Część 2

Poniżej używam zamiennie imion “Gajowniczek”, “Gajowy”, “dobry doktor” lub “Wojtek”, a także “Michał” lub “Misio” w odniesieniu do Michała Olbińskiego, innego bliskiego towarzysza w Afryce.

Krzyś (Krzysztof Albiniak) i Staś (Staszek Stanisław Nowakowski) dwaj nasi kierowcy.

Lonek (Leonard) Adamowicz.

1.

W poniższym tekście odniosę się tylko do tych epizodów, które są związane z Wojtkiem. Szersze opracowanie uwzgledniające resztę uczestników AWA72 musi poczekać na swego autora.

Powiedzenie mówi, że “wybrani przez bogów” umierają przedwcześnie. Najpierw bogowie wyposażali ich we wspaniałe cechy umysłu i serca … a później wyrywali ich z zaludnionego świata.

Czyżbym wyczuwał w ludziach gust bogów, czy co? Moi faworyci odchodzą jeden za drugim.

Najpierw Olędzki aka Stary Kurp. Teraz Gazowniczek aka Gajowy, jak go czule nazywaliśmy. I nie żeby ci dwaj moi „wybrańcy” kwalifikowali się jako “święte postacie”. Daleko im było do tego.

Kryteria „boskich wybrańców” były bardziej skomplikowane niż wierna służba jakiejś opcji moralnej, artystycznej, kognitywnej lub ideologicznej.

Być może, Czytelnik, sam się zorientuje co z poniżej przedstawionego rysu biograficznego Gajowego, wyróżniało Go pośród rówieśników i co mogło zwrócić na Niego uwagę bogów, kimkolwiek by oni (one) nie byli/były. Poniższa relacja, która zgodnie z zapowiedzią trzyma się formuły: chronologia medycznych interwencji plus różne winiety Jego zachowania i wypowiedzi, które charakteryzowały Wojtka i nadawały wyprawie afrykańskiej istotnego smaku. Tych “powiedzonek” i wydarzeń, w których brał udział, nie da się przedstawić w żaden uporządkowany sposób, gdyż wymagałoby to zajęcia przeze mnie stanowiska biografa osoby Wojtka, do którego nie aspiruje.

Tutaj nie rozważam odpowiedzi na pytanie o gust bogów, który zabiera najatrakcyjniejszych spośród nas.

Podaje wersję zapamiętaną z Afryki bez własnych komentarzy. Zdaję sobie jednak sprawę, że pomimo prób neutralności opisu nie sposób abstrahować od mojego życzliwego wglądu w osobę Wojtka.

Z dystansu czasu można wyraźnie dostrzec jak przytaczane w tym tekście epizody zdominowane przez Wojtka układają się w obraz Jego osobowości, czy chce tego jako Autor, czy nie.

Porównuję te „winiety postawy i wypowiedzi” do techniki francuskich impresjonistów polegającej na rysowaniu obrazów za pomocą licznych kropek na płótnie. Po poprowadzeniu niewidocznej linii łączącej kropki miały być one rozumiane, w intencji ich twórców, jako “momenty” dziejące się na skali czasu. Każda z nich nie niesie ze sobą żadnego znaczenia. Dopiero patrząc z dystansu możemy rozszyfrować pojawiające się na płótnie kształty tworzone przez te liczne “pozbawione sensu i celu” same w sobie, kropki. Czasem te obrazy były intencyjnie ukryte przez artystów, a czasem są jeno wytworem wyobraźni odbiorców.

2.

Te punkty, które można nazwać “wyrywkowo dobranymi wydarzeniami”, można porównać do “artefaktów” zachowania. Te artefakty mają wspólny mianownik, bo dotyczą jednego człowieka, tutaj Wojtka Gajowniczka. Są więc jak spójna kolekcja stworzona przez eksperta cum kolekcjonera, który ceni każde ze znalezisk, bo wzbogaca jego zbiór.

W poniższym tekście ja mogę się przyrównać do „zbieracza” epizodów zachowania Wojtka, poprzez obserwacje i zapamiętywanie różnych idiosynkratycznych elementów, składających się na opis uczestnictwa Wojtka w AWA72.

Poniżej przedstawiam swój „zbiór” w, wyżej wspomnianej kolekcji, przybliżającej postać Wojtka.

3.

Nie zawarłem w tym zbiorze wszystkich możliwości. Moja sympatia do Wojtka była naczelną zasadą, dyktującą co zamieścić a co odrzucić. Selekcjonuję tutaj materiał odrzucając najlepsze i najgorsze momenty. Każdy z krańców moralnego spektrum zapraszałby do niemile widzianej oceny. Chcę przedstawić Wojtka takim, jakim był, wspaniałym kompanem, wybitnym zawodowym medykiem i współczującym, choć czasem emocjonalnie nadto żywiołowym człowiekiem.

Trudno mi się pogodzić z wiadomością o śmierci Wojtka. Utrzymywałem z nim kontakt przez ostatnie 50 lat, umawiając się na “spacery/rozmowy” za każdym razem, gdy przyjeżdżałem do Polski. Jego śmierć skłoniła mnie do przypomnienia sobie minionych 50 lat (zarówno w Afryce, jak i w czasach post-afrykańskich) i zapisania tego w sposób, w jaki “go pamiętam”.

4.

Poniżej przedstawię Wojtka, barwnego, energicznego i złożonego człowieka, najdokładniej jak potrafię.

Mieliśmy ogromne szczęście, że niemal w “ostatniej chwili” znaleźliśmy tak kompetentnego i oddanego swojej profesji lekarza, jakim był Gajowy. Wojtek musiał mieć świadomość, że poświęcił swoją przyszłą karierę dla ponad rocznej podróży po Afryce. Mieliśmy szczęście, ale nie zdziwienie decyzja Wojtka. Każdy z nas poświęcił swój rozwój zawodowy dając się “uwieść” romantycznemu obrazowi Afryki. Jak wspomniałem w Części 1, kilku z nas, w tym ja, wybrało niepewne “kanarki na afrykańskim dachu”, zamiast zadowolić się “wróblem w garści”, aka „rajskim ptakiem” w moim przypadku. Stawiając na rozwój kariery w branży naukowej miałbym zagwarantowaną pozycje wśród prestiżowych elit branży elektronicznej.

5.

Wojtek był typem sportowca. Był kiedyś mistrzem na dystansie 100 m motylkiem. Kobiety go uwielbiały. Takie typy przedkładają aktywność na świeżym powietrzu nad obowiązki w szpitalach, bibliotekach, na licznych, rozwijających karierę konferencjach. Lekarze pokroju Wojtka pracują w odległych i niebezpiecznych miejscach jako Lekarze bez Granic. Propozycja wyjazdu z nami musiała przemówić do niego silniej niż jakakolwiek opcja ustatkowania się w dobrze zorganizowanym życiu zawodowym w Warszawie.

Niedawno przeszedł proces separacji, więc Afryka mogła być potrzebnym lekarstwem na posiniaczoną duszę. Nigdy nie rozmawialiśmy o jego życiu osobistym.

6.

Wśród wszechstronnego wyposażenia we wszystko co podróżnicza dusza mogła zamarzyć, dostaliśmy epoksydowe pudełka, od firmy farmaceutycznej Polfa, w których mogliśmy przechowywać wszystkie przedmioty, prywatne i te do użytku wspólnego. Wojtek wypełnił dziesięć skrzyń medykamentami i sprzętem chirurgicznym, na każdą możliwą okoliczność.

Epoksydowe skrzynie były wytrzymałe i lekkie. Łatwo było dowolnie zmieniać ich położenie w samochodach.

Szczególny nacisk Wojtek położył na możliwość przeprowadzenia operacji wycięcia zainfekowanego wyrostka robaczkowego, gdyby zaistniała sytuacja zagrażająca życiu, z dala od wyposażonego odpowiednio szpitala.

Prawdą jest, że ludzie z trudem zarabiali wystarczająco dużo pieniędzy, aby sfinansować swoje proste życie, wiążąc „finansowy koniec z końcem”. Ale, dla niektórych szczęściarzy jak my, rzeczy “za darmo” płynęły z różnych kierunków. Finansowanie i hojne wyposażanie Wyprawy, ocierało się o ekstrawagancje, w czasach, kiedy służbie zdrowia brakowało pieniędzy na podstawowe sprzęty medyczne. Widać, że dystrybucja dóbr nie bywa równomierna. Przysłowie mówi, że bywa się „raz na wozie, raz pod wozem”. I tym razem byliśmy „na wozie” i bonanza przytrafiła się nam.

Nasz przypadek był jak wygraniem losu na loterii.

Podobne przygotowania poczynili kierowcy i mechanicy, którzy spakowali dwa dodatkowe silniki i wszystkie akcesoria na wypadek, gdyby musieli wykonać gruntowna renowacje naszych samochodów. I rzeczywiście, taka konieczność wystąpiła na środku pustyni.

7.

Piękne samochody zdawały się przedkładać wygląd nad wytrzymałość terenowa. Wymagało to wymiany większości części, jedne po drugich. Krzysztof i Staszek napisali obszerne raporty, szczegółowo opisujące słabe punkty konstrukcji i to, co należy poprawić w następnej generacji wojskowych ciężarówek.

8.

Gajowy był człowiekiem romantycznym, jak my wszyscy. Na stoliku kawowym w jego domu była książka z egzotycznym przedstawieniem dżungli i dzikich zwierząt autorstwa Rousseau, francuskiego malarza słynącego z fantastycznych wizji egzotycznej przyrody.

Książka ta, przywieziona przez kogoś z podróży do Francji, rozpalała fantazje Wojtka odkąd sięgał pamięcią. Możliwość dołączenia do wyprawy do Afryki wydawała się propozycją rodem z dziecięcych marzeń.

9.

Dla niektórych z nas kontemplacja bałtyckiego horyzontu pełniła podobną rolę jak dla Wojtka sztuka Rousseau. Dla innych był to zwyczaj obserwowania samolotów lądujących i startujących z warszawskiego Okęcia. Jeszcze dla innych był to trekking w Tatrach i dreszczyk emocji, że idąc niektórymi szlakami wchodzą o kilka metrów w “zagranicę” przekraczając granicę polsko-czechosłowacką.

W literaturze psychologicznej nazywa się to “zew nieznanego”, a leśnicy nazywają to “wołaniem puszczy”. Można to nazwać “zaproszeniem do wolności”. Bez względu na to, jak to nazwiemy, chcieliśmy wyjść poza znaną nam krainę… a Afryka wydawała się “lądem, który ucieleśniał” wszystkie te ledwo wyartykułowane drżenie naszych dusz.

10.

Wojtek przy ognisku opowiadał o swoim synu Wojtku (Juniorze). Nie miał bliskich relacji z chłopcem (zrozumiałem, że miał około 10 lat). Jednak myśli o chłopcu zajmowały umysł i serce Wojtka o wiele bardziej, niż był w stanie, lub chciał, dobrowolnie się do tego przyznać.

Martwił się, jak będzie postrzegany przez syna, z którym nie spędzał zbyt wiele czasu (jak zrozumiałem), głównie z powodu trudnych relacji z matką syna.

Wojtek najwyraźniej nie był gotowy na ustatkowanie się w życiu rodzinnym.

Gajowy spekulował, że dla syna posiadanie ojca podróżującego po egzotycznych zakątkach Afryki będzie powodem do dumy. Gajowy pisał listy i prowadził pamiętnik, zapisując jak najwięcej, z zamiarem przekazania ich Wojtkowi (juniorowi). Wojtek miał nadzieję, że ręcznie pisane dokumenty będą mogły być kiedyś przeglądane przez przyjaciół chłopca.

11.

Kolejna romantyczna wizja relacji międzypokoleniowych.

Gajowy był bardzo młodym ojcem. Reszta z nas nie była dotknięta tym głębokim doświadczeniem, przez które przeszedł. Bliżej nam było do nastolatków niż do poważnego stanu dorosłego mężczyzny.

11a.

W samochodach mieliśmy zainstalowane krótkofalówki. Formalnie po to, by nie tracić kontaktu podczas pustynnych burz. W spokojne dni rozmawialiśmy z samochodu do samochodu podczas monotonnej jazdy po pustynnych dzikich “drogach”.

Krótkofalówki pozwalały nam utrzymywać kontakt z niektórymi amatorskimi stacjami radiowymi w oazach, które mijaliśmy. Stacje te czasami nawiązywały kontakt z polskimi krótkofalowcami. Byliśmy zaskoczeni, podróżując po bezdrożach, gdy od czasu do czasu, nasze postępy były śledzone i obserwowane przez nieznanych nam entuzjastów radiowych, którzy jednak wiedzieli o naszych “heroicznych” postępach.

12.

Krajowi radioamatorzy, poprzez afrykańskich kolegów, przekazywali wiadomości: “powodzenia! I uważaj, aby nie zostać zjedzonym żywcem w tych dzikich regionach”. Było to ambarasujące dla nas i ubliżające miejscowym radioamatorom, dlaczego Polacy, w dalekim kraju, niepokoili się, byśmy się nie znaleźli na liście menu. Wyjaśnialiśmy, że to nic poważnego, i ze to takie narodowe, głupie żarty, adresowane do podróżujących po dalekich krainach.

Afryka w tamtych czasach była dla większości Polaków przestrzenią niebezpieczną i tajemniczą jak Kosmos. Byliśmy ucieleśnieniem fantazji o wolnym i niebezpiecznym życiu, które wymykało się większości naszych rodaków. Dla równowagi, ta wizja musiała tez mieć cenę. Stad wyobrażenia o kanibalizmie, bandytach i przesadnie roztrząsanych niebezpieczeństwach ze strony fauny.

Dobrze czuliśmy się w roli nosicieli polskich fantazji o wolności, o przygodzie i osobistej odwadze.

13.

Podróż przez Europę była prosta.

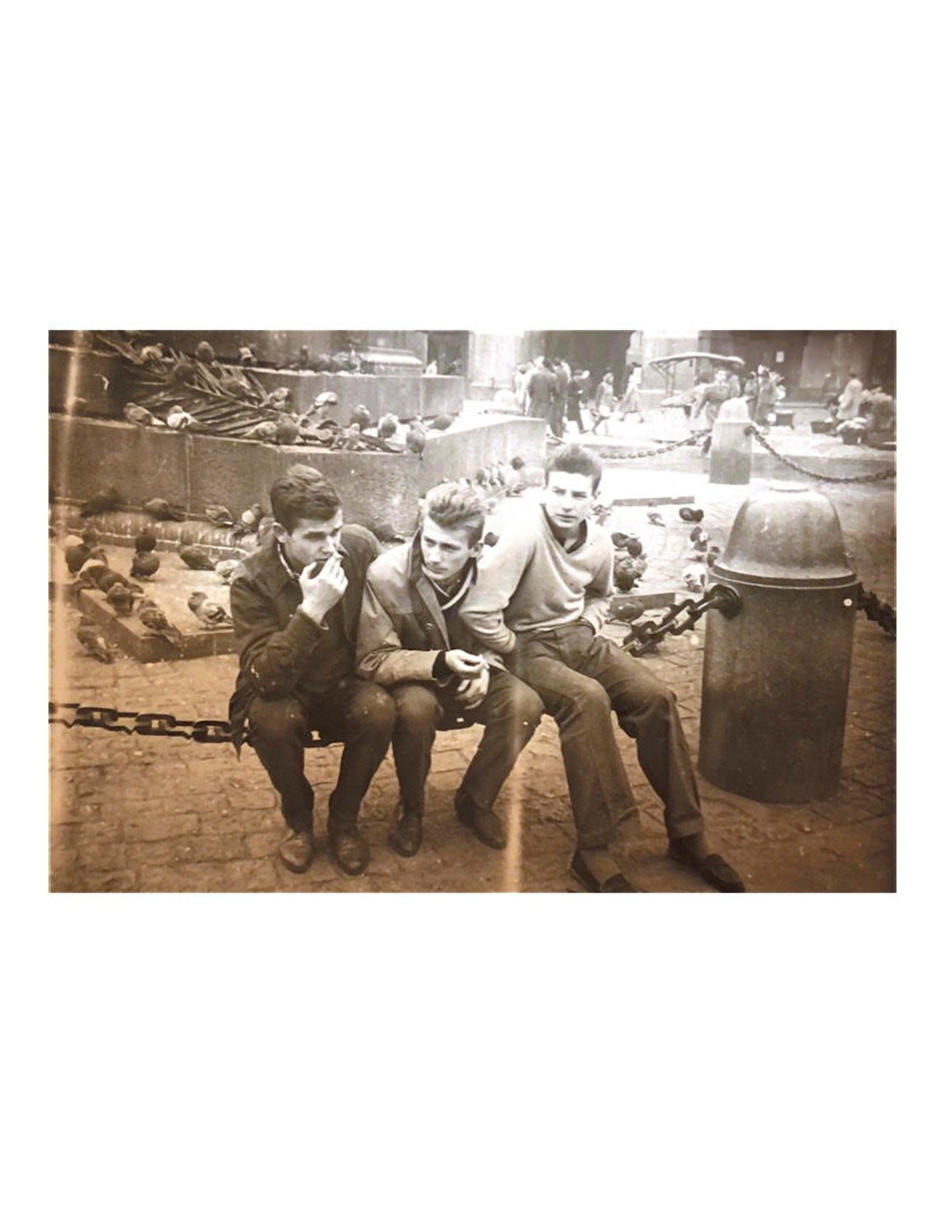

W Budapeszcie gościł nas polski wicekonsul Wojciech Salapski. Kolejny “Wojtek” w tym tekście. Można by się zastanawiać, czy po II wojnie światowej istniały inne imiona dla dzieci płci męskiej niż Wojtek i Marek.

W Zagrzebiu spotkaliśmy pana, który znał duże fragmenty Mickiewiczowskiej epopei Pan Tadeusz. Napotkany nieznajomy deklamował cale fragmenty w chorwackim tłumaczeniu i polskim oryginale. Kiedy doszliśmy do Koncertu Jankiela, który ja też znalem na pamięć, to obaj mieliśmy łzy w oczach. Jak jeszcze wyznałem, że moje nazwisko „Dabrowski” jest takie samo jak nazwisko generała wielbionego przez cymbalistę, to padliśmy sobie w ramiona, choć znaliśmy się zaledwie od godziny. To spotkanie uświadomiło nam, że kultura chorwacka jest bardzo zbliżona do polskiej, a ta ostatnia jest tutaj uważana za wiodący filar cywilizacji europejskiej. Nawet nasze hymny narodowe miały tę samą melodię, choć inne brzmienie.

Kultura jednak może zbliżać ludzi bardziej niż wspólna historia.

No i dobrze!!! Podniosło to naszą samoocenę… tak silnie atakowaną do niedawna przez poczucie minimalistycznych aspiracji narodowych, dominującym uczuciu powszechnego niedostatku, tragicznej historii i zmarginalizowaniu na europejskiej scenie.

Mieliśmy “prezentować Polskę w świecie”, choć w naszych duszach i umysłach nosiliśmy “szczątkowe” kompleksy niższości wobec ludzi Zachodu. Dzięki takim spotkaniom jak to w Zagrzebiu poczuliśmy się “zaprezentowani” podnoszącymi na duchu słowami, dzięki którym poczuliśmy, że jesteśmy obecni kulturowo poza naszymi, na poły nieprzepuszczalnymi, granicami.

14.

W Wenecji (Gajowy, Olbiński i ja) spotkaliśmy bogatego amerykańskiego turystę polskiego pochodzenia, który zrobił się bardzo sentymentalny widząc nas w pełnej krasie, podróżujących pięknymi samochodami i elegancko ubranych. Był zdumiony, że “komunistyczny” rząd wydał nam wizy podróżne.

Dał nam zwitek pieniędzy (naprawdę staraliśmy się sprzeciwić przyjęciu tego gestu), który później, na wiele miesięcy, uzupełnił nasze tygodniowe kieszonkowe w wysokości 3,5 $.

Obecnie, “nie pamiętam”, czy ten dar został zgłoszony Kierownictwu, w celu „zaksięgowania” jako „przychód” Wyprawy, do rozliczenia po powrocie do Kraju.

14a.

Mieliśmy potencjał do zarobienia niewielkich pieniędzy po drodze, wykorzystując nasze mocne samochody, jako cenne aktywa. Często trzeba było wyciągnąć jakiś pojazd z błota lub odholować do warsztatu. Kiedyś, jeszcze w Europie, zarobiliśmy kilka dolarów wyciągając, mechaniczna wyciągarką, prywatny samochód z głębokiego rowu. Nie wiedzieliśmy, ile warta była nasza interwencja. Z wdzięcznością przyjęliśmy wszystko, co dał nam szczęśliwy posiadacz uszkodzonego samochodu.

15.

Niektórzy ludzie udzielili nam szczegółowych informacji, w jaki sposób, z samochodami takimi jak nasz, mogliśmy zarobić duże pieniądze, napełniając nasze baki i zapasowe kanistry benzyną w jednym kraju i sprzedając ją w innym zaraz po przekroczeniu granicy.

Byliśmy pełni ekscytujących nadziei na podreperowanie naszych budżetów dzięki tak wielu możliwościom, które mogły pojawić się na naszej drodze.

16.

Ale nie obyło się bez zgrzytów. Eugeniusz trzymał się przekonania, że organizatorem wyprawy jest Uniwersytet …. i w związku z tym wszelkie pieniądze (jeden dolar wydawał nam się dużą kwotą) powinny „słusznie” należeć do tej instytucji.

Miał ambicję wydać jak najmniej i najlepiej przywieźć z powrotem całą pozostałą, a także zebraną po drodze, kwotę.

Oczywiście nie była to ambicja podzielana przez resztę nas. Uczciwość fiskalna to ważna rzecz, ale jak wszystkie moralne wartości, powinna była być rozpatrywana pod kątem kontekstu.

Kiedyś, już w Afryce, pośrodku Sahary, rozpadła się przyczepa. Zgubiliśmy koło. Miejscowy garaż zaoferował sto dolarów. Eugeniusz odmówił rozumując, że rzeczona przyczepa nie jest „nasza własnością” lecz wojska, które nam ja „wypożyczyło”. Przez następne dni, a nawet tygodnie, Eugeniusz organizował transport wraka do portu w Algierze, z zamiarem przetransportowania go polskim statkiem do Kraju. Cena, jak to w Polsce bywało, nie „grała roli”. Ważna była zasada.

Żaden z nas nie przykładał ręki do wysiłków Eugeniusza, protestując w ten sposób przed ekstremalna „solidnością” cum „uczciwością” Eugeniusza. Słusznie uważaliśmy, że porządny posiłek w jakiejś wiejskiej knajpie, za otrzymane 100 USD, byłby mile widzianą odmianą od codziennej diety „wołowiny w sosie własnym”.

O ile wiem, przyczepa – wrak została gdzieś zagubiona w drodze do portu. Ale, jak uczyła ideologia socjalistyczna, najważniejsze by cnota obywatelska została zachowana, bez względu na koszty finansowe.

Zresztą nie trzeba się powoływać na „moralność socjalistyczną” by wytłumaczyć stanowisko Kierownika.

Już Oscar Wilde zdefiniował dwie przeciwstawne postawy: idealistyczną i pragmatyczną. Ta pierwsza opiera się na wierności ideałom bez względu na koszty. Ta druga, kieruje się ceną i doraźną korzyścią, nie zważając na ideały.

Eugeniusz był idealistą.

16a.

Pojechaliśmy wzdłuż wschodniego wybrzeża Hiszpanii przez Barcelonę i Malagę. Popłynęliśmy promem do Ceuty na afrykańskim wybrzeżu.

Nie zostaliśmy tam. Tego samego dnia przekroczyliśmy granicę z Marokiem. W Maroku natknęliśmy się na pierwszy wypadek medyczny.

16b.

Pierwszego dnia po wylądowaniu na afrykańskiej ziemi ruszyliśmy w kierunku Marrakeszu. Nocleg zaplanowaliśmy gdzieś w okolicach tego słynnego miasta. Jadąc powoli uliczkami jakiejś małej osady spotkaliśmy wielu młodych arabskich chłopców. Niektórzy z nich pilnowali straganów z różnymi turystycznymi bibelotami. Rozpoznali, że jesteśmy z Polski i zaczęli wołać po polsku “dobrze”, “pani kupi ta pamiątki” itp. Niesamowite. Wyglądali na mniej niż dziesięć lat.

Pomachaliśmy do nich.

17.

Kilku z nich wskoczyło na dyszel małej przyczepy, którą holował jeden z naszych samochodów. Jeden z nich mógł łatwo poślizgnąć się i wpaść pod koła, raniąc siebie i wpędzając nas w duże kłopoty.

Kierowcy zatrzymali się. Michał wysiadł, by słowami i gestami odeprzeć małych intruzów. W tym momencie spadł na niego grad kamieni. Nie wyglądało to nawet jak brutalny atak… ale jak kulturowy sposób wyrażenia łagodnego niezadowolenia w ich imieniu. To mogła być lekcja “niewinnej przemocy”.

Gdyby to nie były kamienie ale, na przykład pomidory, skończyłoby się na ogólnej wesołości i zakwalifikowane jako składnik przyjaznego powitania.

Ale Michał został ranny. Jeden z kamieni uderzył go w czoło. Michał obficie krwawił.

18.

Podjechaliśmy na plac małego miasteczka, przez które właśnie przejeżdżaliśmy. Od wypadku minęło nie więcej niż 20 minut, a plac już wiedział o nas i incydencie. Z jednego z budynków wyszedł brodaty mułła. Przepraszając za to, co się stało, zaprosił nas do domu modlitwy, abyśmy położyli rannego Michała na stole.

W tym czasie Gajowy sprawnie przygotował się do akcji. Przybył do rannego Michała ze wszystkimi niezbędnymi narzędziami chirurgicznymi. Zszycie rany wykonał z precyzją i kompetencją doświadczonego chirurga. Całą akcję medyczną obserwowaliśmy z odległości kilku metrów. Byliśmy pod wrażeniem i pewni, że jesteśmy w dobrych rękach pod opieką medyczną.

19.

Po operacji Michał dołączył do reszty nas. Mułła przeprosił w imieniu swoich rodaków za sposób, w jaki zostaliśmy przywitani pierwszego dnia w Afryce. Na szczęście wychowaliśmy się w świeckim kraju, gdzie ani religia, ani różne przesądy nie miały nad nami władzy. O ile mi wiadomo, nikt z nas nie potraktował tego incydentu jako “zły omen” zwiastujący źle dla naszej przyszłości.

Zdawaliśmy sobie sprawę, że to tylko dzieci zawiniły, a zachowanie “osoby oficjalnej”, czyli miejscowego mułły, było bez zarzutu.

20.

Po kilku dniach w Maroku zdałem sobie sprawę, że incydent z kamieniami miał swoje lokalne, kulturowo uświęcone podłoże. Za każdym razem, gdy Jacek i ja próbowaliśmy filmować lub fotografować mężczyzn siedzących na poboczu drogi, okazywali oni swoje niezadowolenie z naszego projektu, sięgając po jeden z przygotowanych wcześniej kamieni. W ten sposób zapowiadali, że rzucą w nas tym kamieniem, jeśli się od nich nie odczepimy. Za którymś razem, poirytowany Jacek, na ich ostrzegawczy gest, podniósł z ziemi niewielki kamień. Splunął na niego i rzucił za siebie. Miało to dać do zrozumienia, że lekceważymy ich groźby. Spluwając na trzymany kamień, Jacek sygnalizował, że my gardzimy ich reakcją wobec nas, w końcu gości w ich kraju. Wydawało mi się to zuchwałym i niebezpiecznym gestem. Mogli poczuć się urażeni w swojej dumie i kulturze. Na szczęście dla nas Jacek, doświadczony etnograf, trafnie ocenił sytuację. Siedząca na poboczu grupa mężczyzn pozytywnie zareagowała na gest Jacka. Odłożyli kamienie i zaczęli się śmiać z tej bezgłośnej pantomimy gestów. Pozwolono się też sfotografować. Na koniec uścisnęliśmy sobie dłonie w geście międzykulturowego pojednania.

21.

Był jeszcze jeden incydent w Maroku z małymi chłopcami, który uzmysłowił mi jak ważne jest trzymanie odpowiedniego dystansu z naszej strony. Przysłowie mówi, że „dobre ploty tworzą dobrych sąsiadów”. Filozof Bauman pisze, że dobre relacje polegają na sztuce „bycia razem, osobno”. Jeszcze inna ludowa mądrość mówi, że „familiarity breeds contempt”. Czyli, że zbyt wielka bliskość (w domyśle ludzi nie połączonych intymnym związkiem) spoufala i budzi wzajemną niechęć.

Doradzano nam, żeby okalać nasze obozowiska grubą linią i w ten sposób dzielić teren na nasz i nie nasz. Poniżej opisuję incydent, który miał miejsce ponieważ, ta dobra rada, nie była rygorystycznie przez nas przestrzegana.

21a.

Obozowaliśmy na pustych przestrzeniach niedaleko osad. Od samego rana odwiedzali nas zaciekawieni przechodnie. Mężczyźni przychodzili się z nami przywitać. Kobiet nie było widać. Dzieci stały w niewielkiej odległości chichocząc głośno i natarczywie domagając się od nas “prezentów” Cado !!! Cado !!! – powtarzały bez przerwy. Niektóre z nich, zawsze chłopcy w wieku od 6 do 12 lat, stawali się coraz odważniejsi i próbowali zabierać różne małe przedmioty z obozu.

Otoczyliśmy obóz liną wyznaczającą granice, by dzieciaki nie wkraczały na “nasz teren”. Jacek pisał przy prowizorycznym stole. Chłopcy zaczęli mu dokuczać i rzucać w niego małymi kawałkami ziemi i gliny. Zareagował radośnie, ale, jak w jego zwyczaju, “bardzo specyficznie”. Robił do nich miny lub wydawał różne niewerbalne pomruki.

22.

Chłopcy zareagowali śmiechem, właściwie rozumiejąc, że on, być może nieświadomie, zaprasza ich do jakiejś zabawy. Jacek miał w sobie dużo “dziecka”, a spotkanie z “równymi sobie” przyniosło mu ulgę od konieczności zachowywania się zawsze w “poważny” sposób podczas Wyprawy. Po alkoholu zmieszanym z tabletką valium Jacek przemieniał się z łagodnego doktora Jekyll w pana Hyde. Zwykle cicho mówiący, z refleksją w głosie, mógł w nowym wcieleniu krzyczeć i głośno mruczeć. Alkoholu nie było, ale Jacek mógł podkraść tabletkę valium z tajnych zapasów lekarza.

22a.

Byłem zajęty przekładaniem skrzyń na samochodzie w celu dotarcia do materiałów piśmiennych. Inni robili na prędce notatki z ostatnich dni lub prali swoje ubrania. Niektórzy udali się do najbliższej osady.

Nagle usłyszałem jak Gajowy woła mnie wzburzonym głosem, żebym szybko przybiegł i pomógł ratować Jacka. Wyskakując z samochodu zobaczyłem Wojtka próbującego odciągnąć Jacka od grupy chłopaków, którzy przekroczyli linę „demarkacyjną” i zaczęli bezpośrednio molestować Jacka.

Wojtek był silnym mężczyzną, więc udało mu się odciągnąć młodych napastników i zaprowadzić Jacka w bezpieczne miejsce. Miał podartą koszulę i wyglądał na rozczochranego.

Wojtek przytomnie nakazał ewakuację pod samochodową plandekę. Kilka kamieni przeleciało nam nad głowami. Samochody miały złożone przednie szyby, więc nie groziło im uderzenie. Udało nam się zejść z oczu napastnikom. Nie wdaliśmy się w żadną wymianę inwektyw.

W razie zaognienia konfliktu byliśmy na straconych pozycjach. Mogło być groźnie. Mogli nas obrzucać płonącymi pochodniami.

Na nasze szczęście nie doszło do eskalacji. Reszta „naszych” zaczęła powracać do obozowiska i chłopaki wycofali się. Prawdopodobnie by zdążyć na czas na domowy, wieczorny posiłek.

23.

Wojtek był pewien, że rozerwaliby Jacka na strzępy, gdyby nie zauważył, co się dzieje. Niewinnie wyglądający chłopcy” zaczęli ściągać Jackowi spodenki itp.

Sytuacja niebezpiecznie przypominała scenę z filmu Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) z Katharine Hepburn w roli głównej, w której młody i naiwny Amerykanin na wakacjach w Hiszpani, zostaje rozszarpany na strzępy przez grupę młodocianych, zachowujących się jak sfora psów, żądna krwi.

Jacek był w szoku i zdezorientowany tym co się przed chwilą mogło wydarzyć.

Przyszło mi do głowy kilka refleksji.

Po pierwsze, doktor Wojtek był przygotowany do interwencji w sposób zapobiegawczy, przewidując problem. Jak mówi powiedzenie “lepiej zapobiegać” niż “leczyć” Był dobrze wyszkolony w tej podstawowej medycznej mądrości. Obserwował Jacka i chłopców przez jakiś czas gotowy do interwencji. Taka czujność niewątpliwie uratowała Jackowi, jeśli nie życie, to co najmniej poważne fizyczne i psychiczne obrażenia.

Po drugie, w każdym związku należało zachować odpowiedni dystans. Nadmierna bliskość rodzi niekontrolowane zachowania, niczym atawistyczne instynkty znane ze świata zwierząt.

Afrykanie ostrzegali mnie, jak zachować się w przypadku spotkania z lwem, dzikim psem czy jakimkolwiek drapieżnikiem. Żelazną zasadą jest to, by nigdy nie zacząć uciekać ani w żaden inny sposób okazywać strachu. Należy trzymać się ziemi i utrzymywać kontakt wzrokowy z potencjalnym napastnikiem. Atakujące gesty, pozorujące kontratak, może być stosowany wyłącznie wtedy kiedy napastnik ma drogę odwrotu.

Po trzecie, mądrość, jak się zachować, nie polegała na założeniu, że agresja ze śmiertelnymi konsekwencjami, jest przejawem zła. Cały dramat mógł rozgrywać się na instynktownych poziomach “poza dobrem i złem”. Trudno uznać zabójczego lwa za “złe stworzenie”. Atakujący chłopcy mieli miłe, niewinne spojrzenia.

Zachowanie, takie jakie spotkało Jacka, wymyka się ocenie moralnej. I trudno się z refleksją pogodzić, że w grupie (czy to w wymiarze koleżeńskim czy na większą skalę np. narodową) ludzie mogą się inaczej zachowywać niż w pojedynkę.

24.

Jak powiedział jeden z odwiedzających nas mułłów, któremu opisaliśmy ten incydent: w ich przypadku nasza duchowa edukacja nie rozwinęła jeszcze sztuki kontrolowania aspołecznych odruchów .

Wychowywanie młodzieży w duchu empatycznego zachowania i kontroli agresywnych impulsów, jest długim procesem, podczas gdy instynkty, które dzielimy ze zwierzętami, są w nas, od urodzenia.

25.

Później dowiedziałem się o “niewinnym sadyzmie”, czyli krzywdzie jaką ludzie wyrządzają blisko spokrewnionym przyjaciołom lub członkom rodziny, czerpiąc z takiego działania trudny do zidentyfikowania rodzaj przyjemności, czy rozładowania napięć emocjonalnych.

“Niewinny sadyzm” pochodzi z jakiejś psychicznej głębi i jest czymś spontanicznym, innym niż zorganizowane i sformalizowane praktyki sadystyczne.

Mułła przyznał, że zachowanie wiejskich chłopaków szwendających się po okolicy, była szczególnie niebezpiecznym środowiskiem dla tego, tak zwanych, “niewinnych morderstw”.

Mówi się, że „okazja czyni złodzieja”. Wygląda na to, że również okazja czyni morderców z grupy, skądinąd sympatycznej garstki młokosów.

Mułła opowiedział, że od czasu do czasu znajdowano przy drodze martwe ciało “świętego” lub bezdomnego, ze śladami okaleczenia. O takie czyny podejrzewano grupy maruderów z wioski.

Trochę zmroziło to nam krew. Poczuliśmy się bezpieczniejsi w grupie dwunastu młodych, zdrowych i wysportowanych.

25a.

Następnego dnia, znajomy mułła, odwiedzający nasz obóz, zwrócił uwagę, że Biblia umieszcza niestabilność ludzkiej psychiki w centralnym wydarzeniu Nowego Testamentu.

W Niedzielę Palmową, w czasie wjazdu Jezusa do Jerozolimy, tłumy entuzjastycznie witały Go, rzucając przed Nim liście palmowe. Zaledwie pięć dni później, przypuszczalnie ten sam tłum, domagał się ukrzyżowania Jezusa. Wyraźna metafora tego, że nawet Bóg nie był w stanie ustabilizować nastrojów.

Jak moglibyśmy, kontynuował mułła, mieć nadzieję na coś lepszego.

26.

Doświadczenie z “groźbami ukamienowania” przekonało mnie, że mamy do czynienia z “kulturą rzucania kamieniami”. Biblia zaleca “kamienowanie” jako formę egzekucji za różne wykroczenia, ze szczególną gorliwością skierowaną w stronę niewiernych kobiet.

W Marrakeszu biblijna atmosfera wrzała na każdym kroku. Mówcy wspinali się na skrzynie i przemawiali do garstki słuchaczy. Zrozumiałem, że byli to nawiedzeni moraliści, samozwańczy prorocy, którzy chcieli uwolnić swój naród od boskiego potępienia.

Z łatwością można było sobie wyobrazić Jezusa wygłaszającego kazanie na Górze… zapewniającego słuchaczy o ich wysokim statusie moralnym i szczególnej przychylności Boga wobec nich, wynikającej ze stanu ich ubóstwa.

27.

Na kolejny incydent medyczny musieliśmy czekać do grudnia.

Do Tamanrasset przyjechaliśmy 31go grudnia. Rozbiliśmy obóz w pobliżu tego pustynnego miasta pełnego klimatycznych scen przemieszczających się przez miasto karawan wielbłądów. Karawany były prowadzone przez Tuaregów, chudych, surowo wyglądających, wysmukłych mężczyzn, odzianych w niebieskie szaty, z mieczami wystającymi spod tunik. Glowy i szyje mieli opatulone czarnymi turbanami, częściowo zakrywającymi ich twarze. Wyglądali jak żywcem wzięci z filmów hollywoodzkich o Lawrence z Arabii, legendarnym przywódcy powstań arabskich przeciw Turkom.

Tamanrasset było miastem zbudowane z czerwonej gliny, położonym u podnóża gór Hoggar. Same góry wyglądały jak wielkie organy, zbudowane ze skalnych filarów w kształcie monumentalnych rur. Przewodnik wyjaśniał, że jest to dzieło erozji, a rury powstały w wyniku specyficznej krystalizacji lawy wiele lat temu.

28.

W górach ukryta była pustelnia legendarnego mnicha, ojca Foucault, który wiele lat wcześniej przybył w te rejony oddając się kontemplacji urokliwego krajobrazu i nauk Jezusa, w warunkach skrajnego ubóstwa. Nawiązał kontakt z Tuaregami. Opracował gramatykę i słownictwo ich języka. Szerzył chrześcijaństwo. Zginał śmiercią męczeńska i został, ostatnio, kanonizowany przez papieża.

Sześcioro z nas pojechało jednym samochodem po górskiej ścieżce. Małe kamienne schronienie, w którym Foucault mieszkał przez wiele lat, znajdowało się na poboczu polnej drogi. Góry były ciche. Bez ludzi. Tylko wiatr zdawał się grać kantaty Bacha na kamiennych piszczałkach.

Zostałem sam w kamiennej chatce, bez szyb, z dużym pustym otworem, który kiedyś mógł służyć za okno. Było zimno. Koniec grudnia. Patrzyłem przed siebie na górzysty horyzont, stopniowo zapadając się w „słodka absencje od swiata”. Ostatkami świadomości wyobrażałem sobie obecność sławnego, byłego, użytkownika tej „wygnanki”, kołysanego do kontemplacyjnego niebytu, pogwizdywaniem wiatru w szczelinach kamiennego szałasu.

Nauka technik medytacyjnych jakie sobie przyswajaliśmy przed Wyprawa, pod okiem magistra Paska, teraz przydała się w praktyczny sposób. W sprzyjającym otoczeniu górsko – pustynnym, sięgnąłem po wewnętrzy spokój i mini ekstazę. Czułem się zatopiony w stan obiecywany przez nauczycieli yogi i wyglądany przez adeptów tajemnego nauczania. Nie dziwiło wiec mnie to, ze ojciec Foucault porzucił zgiełk i blichtr towarzyszący życiu francuskiego żołnierza, na rzecz spartańskiego żywota, przepełnionego wewnętrzną radością, do jakiej aspirują i o jakiej marzą, wyznawcy wszelakich systemów religijnych.

Towarzysze pojechali eksplorować inne części gór. W pustelni, z ciepłym pustynnym wiatrem wiejącym w twarz, wpadłem w autohipnozę, z której wyszedłem po kilku godzinach medytacji. Moi towarzysze cierpliwie czekali, aż dojdę do siebie.

Ich cierpliwość mogła być również wytłumaczona faktem, że ciężarówka pełna młodych Francuzek podjechała w pobliże pustelni. Widząc, po wyjściu z letargu, moich towarzyszy flirtujących, śmiejących się i bawiących z wesołymi młodymi kobietami, mniej więcej w naszym wieku, nie wiedziałem, czy już wyszedłem do “rzeczywistości”, czy wciąż jestem w la la land.

Okazało się, że dziewczyny, niedawno, tak jak my, przyjechały do Tamanrasset, również były na biwaku poza miastem i również, tak jak my, nie miały dobrych pomysłów co robić w Sylwestra. Nie mogło być więc lepiej. Zgodziliśmy się (entuzjastycznie) spędzić wieczór razem. Mieliśmy czekać na nie przed pocztą i razem udać się na nasz biwak, za miastem.

Co prawda byliśmy w Algierii, oficjalnie kraju muzułmańskim z zakazem spożywania alkoholu, ale przedsiębiorczy Arabowie, wiedząc, że Tamanrasset odwiedzają turyści, znaleźli sposób, by “prawie oficjalnie” sprzedawać francuskie wino w 10-litrowych, dużych, nieporęcznych, nieoznakowanych, szklanych beczułkach.

29.

O 22:00, jak uzgodniliśmy w górach, naszych francuskich “porywów serca” nie było. Ani o 23:00, ani o północy w Sylwestra. Było oczywiste, że ”dały nam kosza” z jakiegokolwiek powodu. Nie mogliśmy “uwierzyć”, że mogły mieć lepszą ofertę niż ta, którą im przedstawiliśmy. Przecież się tak dobrze prezentowaliśmy !!!

Nasza frustracja zaczęła sięgać zenitu. Piliśmy wino, kupione na cały wieczór, prosto z beczułek, bezczelnie, siedząc na krawężniku miasta, prawnie zabraniającego picie alkoholu.

Następnie, już z dobrym szumem w głowach, wsiedliśmy do samochodu i zaczęliśmy jechać w kierunku naszego obozu. Nasze telefony, zamontowane na potrzeby chwili takiej jak teraz, nie działały. Miały wyczerpane baterie. Nie mieliśmy jak poinformować reszty, co się stało i dlaczego tak późno wracamy w wieczór Noworoczny.

Przybycie z powrotem, godzinę lub dwie przed północą, z gromadą rozchichotanych młodych kobiet, miało być niespodzianką dla naszych kolegów, o której wszyscy fantazjowaliśmy.

Tym czasem kompletna katastrofa!!!!

Krzyś jeździł jak kierowca Formuły 1. Dobrze, że w noc sylwestrową nie było nikogo na drodze. Usiedliśmy na skrzyniach i głośno śpiewaliśmy jakieś partyzanckie piosenki. Coś w stylu (Rozszumiały się wierzby płaczące. ). Patrzyliśmy przed siebie ze wzrokiem utkwionym w ciemność, w która gnaliśmy „na łeb na szyję” z dużą prędkością.

31.

Prawdopodobnie jedyne drzewo w mieście miało jedną gałąź przecinającą ulicę na wysokości około 2 metrów nad ziemią.

Lonek, w ten konar, uderzył głową , tuż nad lukiem brwiowym. Mogło się to skończyć wielką tragedią, gdyby nasze skrzynie były choćby 10 cm wyżej. Taki przypadek mógł trafić każdego. Siedzieliśmy na skrzyniach i konar tylko musnął moją krótko ostrzyżoną czuprynę.

Ale by było!!! Połowa Wyprawy zmieciona z powierzchni Ziemi zanim się jeszcze na dobre zaczęła!!!! Byłoby to potwierdzenie dominującej opinii w Kraju, że Afryka jest śmiertelnie niebezpiecznym kontynentem. No i te „zatroskane” panie z grona pedagogicznego UW, które uważały, ze jesteśmy za młodzi by się porywać na takie przedsięwzięcie jak AWA72. (Patrz: Gajowniczek Część Pierwsza).

Na szczęście, jak to mówią po angielsku: a small miss is as good as a mile (tzn. że chybienie pociskiem o 1 centymetr jest równie szczęśliwym trafem jak chybienie o milę) mieliśmy dużo szczęścia, nie precyzując na czym to szczęście mogło się opierać.

32.

Lonek został ranny. Mocno krwawił. Wyglądało na to, że dostał wstrząsu mózgu. Chwilowo stracił przytomność.

Wojtek zatamował krwawienie własną koszulą.

Dotarliśmy do naszego obozu i pomogliśmy Lonkowi dotrzeć do namiotu.

Tam, podobnie jak wcześniej w Maroku, Wojtek położył rannego na polowym łóżku i zaczął przygotowywać narzędzia chirurgiczne. Jako pomocnika wziął Maćka Pytla, który miał podstawowe przeszkolenie medyczne. Obserwowałem, jak oczy “dobrego doktora” trzeźwieją i jak metodycznie przygotowuje się do zabiegu.

Tu są nożyczki, tu są nici, tu są waciki” – doktor wymieniał na głos każdy z elementów, co prawdopodobnie było praktyką na salach operacyjnych.

33.

Maciek myślał, że doktor informuje go, wyszkolonego asystenta medycznego, o nazwach poszczególnych elementów , które mają być użyte w akcji chirurgicznej.

Wiem to ! i wiem, w jakiej kolejności należy układać elementy do użycia w zabiegu ” – zaprotestował Maciek.

Nie mówię tego tobie, idioto – krzyknął chirurg w teatralny sposób Wojtek – tylko sam sobie przypominam, jak to ma być ułożone –powiedział emfatycznie doktor, który nadal wyraźnie pachniał winem, które pospołu wypili w dużych ilościach, w oczekiwaniu na wiarołomne Francuski.

Następnie powrócił do głośnego wyliczania: nożyczki, nici, środki dezynfekujące, waciki, …i tak dalej.

Cóż, rzeczywiście, jeszcze godzinę temu można by pomyśleć, że Doktor nie byłby na silach by przeprowadzić zabieg jak ten, ale teraz, jak dobry profesjonalista, odzyskał sprawne ruchy i pewną rękę.

Nie był przecież na ostrym dyżurze, gdy się wydarzył wypadek. W przeciwnym razie by nie brał alkoholu do ust. To pewne. To była wyjątkowa sytuacja.

A wieczór zaczął się tak obiecująco!!!

34.

Lonek doszedł do siebie po kilku dniach. Jednak uporczywy ból głowy przez około tydzień wskazywał na przebyty wstrząs mózgu, którego doznał w Sylwestrowa Noc.

Incydent ten był sygnałem ostrzegawczym, by ostrożnie stąpać po kontynencie i nie dać się ponieść młodości i marzeniom o własnej nieśmiertelności.

34a.

Z Tamanrasset przez Agadez dotarliśmy do Nigru.

Zatrzymaliśmy się na biwak daleko od osad, na półpustynnych polach. Małe czarne kozy skakały po pochyłych drzewach i skubały liście. Ziemia była sucha. Nie było widać żadnych upraw. Znaleźliśmy małe skupisko akacji dające częściową ochronę przed palącym słońcem. Część z nas zdecydowała się na jazdę do stolicy Nigru, Niamey, aby spotkać się z kilkoma wcześniej umówionymi kontaktami politycznymi i akademickimi. Reszta z nas postanowiła odpocząć od gorączkowych tygodni w Algierii i nadrobić zaległości w robieniu notatek i konserwacji sprzętu.

35.

Miejsce było suche na kość, bez deszczu od miesięcy. Nie rozbijaliśmy więc namiotów na noc, ale spaliśmy albo pod gołym niebem, albo pod moskitierami. Rankiem następnego dnia wyszedłem na mały spacer po okolicy. Moją uwagę zwrócił mężczyzna w średnim wieku z małym dzieckiem na rękach. Nie poruszał się. Lekko przekrzywił głowę, gdy się z nim przywitałem gestem ręki. Miał niewielką brodę i ogoloną głowę w stylu muzułmańskiej mody. Stał w niewielkiej odległości od naszego obozowiska. Dziecko się nie ruszało, co wzbudziło moje podejrzenia, że jest chore, a ojciec szuka u nas pomocy.

Poszedłem po doktora.

36.

Lekarz podszedł do ojca z dzieckiem i dokonał oględzin. Dziecko było apatyczne i wyglądało na martwe lub na wpół martwe. Daliśmy ojcu znak by poszedł z nami do obozowiska. Wojtek polecił mi zagotować wodę. Ostudzić i przynieść. Sam poszedł do samochodu i wyjął stamtąd pudełko z lekarstwami. Porozumiał się z mężczyzną sygnalizując, że dziecko ma od kilku dni silną biegunkę. Wojtek potwierdził mi diagnozę, dziecko (był to chłopiec w wieku około dwóch lat) było poważnie odwodnione. Afrykanie, na całym kontynencie, reagują podobnie na biegunkę. Kapuściński pisał o śmiertelności dzieci w różnych częściach swoich raportów. Jest to przypadek źle ulokowanego logicznego myślenia. Rodzice wstrzymują podawanie napojów, rozumując, że to nadmiar płynów w organizmie powoduje biegunkę.

Nalałem przegotowanej, ale już letniej wody do szklanki. Lekarz wymieszał biały proszek, z saszetek UNICEF-u. Oczywiście nie zapomniał o lekach, które mogły być potrzebne w Afryce.

Wojtek z gracją nabierał niewielkie ilości płynu i podawał dziecku na łyżeczce. Po kilku małych łyżeczkach dziecko nadal wydawało się martwe. Chłopczyk nie uczestniczył świadomie w tej medycznej czynności. Wojtek małymi porcjami wlewał płyn do ust dziecka. Wyglądało na to, że płyn powoli docierał do głębszych partii ciała malca, a na efekt trzeba było poczekać.

37.

Opisuję to wydarzenie tak dokładnie, ponieważ po tym, co nastąpiło później, można by ułożyć psalmy pochwalne na cześć “niewidzialnej ręki medycyny”, która doprowadziła do tej interwencji.

Saszetki zawierały sproszkowane minerały i witaminy. To wszystko. Zwykle elektrolity.

Prawdziwy cud!!! A kiedy ktoś był naocznym świadkiem takiego cudu, nigdy go nie zapomina.

Po dziesiątej porcji płynu chłopiec zaczął otwierać oczy. Najpierw jedno oko. Potem drugie.

Po chwili zaczął połykać coraz większe porcje podawanego mu płynu. Wkrótce usiadł w ramionach ojca i objął go za szyję.

Po około 10 minutach. Stał z nogami na ziemi. Wojtek podał ojcu pewną ilość tych saszetek i gestami wyjaśnił, jak zmieszać sproszkowaną zawartość z czystą, najlepiej przegotowaną, wodą.

Po krótkiej chwili ojciec, z dzieckiem trzymanym za rękę, odwrócił się i poszedł gdzieś przed siebie. Wydawało mi się, że widziałem na jego wardze mały uśmiech. Ale żadnej wylewności. Żadnych oznak podziwu czy słownej wdzięczności. Mnie łzy leciały po policzkach. Przecież nigdy nie widziałem tak spektakularnego wyczynu nowoczesnej medycyny. Nigdy tez nie widziałem „cudu” na własne oczy!!

Czułem się jakbym uczestniczył w biblijnym wydarzeniu opisanym przez ewangelistów, w którym Jezus mówi do sparaliżowanego: weź łóżko na ramię i idź w pokoju. Twoja wiara cię uzdrowiła!!!

Tu obyło się bez dramatycznych diagnoz. Bez odwolywania się do wiary. Choć na pewno, ojciec dziecka miał swoje wyjaśnienie jak doszło do tego uzdrowienia.

Ustalenie jakie szamańskie praktyki były w grze, zanim doszło do interwencji naszego doktora, byłoby dobrym tematem do badan antropologicznych.

Dla Wojtka to, oczywiście, nie było żadnym specjalnym wydarzeniem. Jego trening zawodowy przygotowywał go na takie okazje. Lekarze, jak księża na pogrzebach, nie pokazują emocji w czasie niesienia zawodowej posługi.

Ale byłem mu wdzięczny, że widząc na mej twarzy ślady po stróżkach łez, nie nazwał mnie „histerykiem” lub choćby „baba”.

38.

Następnego dnia ojciec uzdrowionego dziecka przyszedł do nas i dał nam kurczaka. Przyjęliśmy go z wdzięcznością, ponieważ …kilka miesięcy na diecie “wołowina w sosie własnym” zaczynało być już nużące.

Cały akt obdarowywania odbywał się w ciszy, bez żadnych gestów ze strony obdarowującego. Staraliśmy się okazać naszą wdzięczność. Różnice w zachowaniu narzucone przez odrębne kultury były widoczne jak na scenie teatru pantomimy. Brak słów zdawał się potęgować dramatyzm wydarzenia.

Kolejny raz zaangażowałem się w “zmartwychwstanie oparte na saszetkach” wiele miesięcy później w północnej Kenii. Odwiedziliśmy osadę Borana, koczowniczych pasterzy.

Wojtka już z nami nie było. Ze względu na żółtaczkę wyjechał na leczenie do Kraju. Byłem jedynym uczniem z doświadczeniem z Nigru jak używać saszetki w sytuacjach przypominających tamten epizod z samotnym ojcem, pokładającym wiarę w nasze medyczne możliwości.

Tutaj, podobnie jak wcześniej w Nigrze, matki “na wpół martwych dzieci” ustawiały się w kolejce po “cudowne leczenie”. I ja, bez słowa, powtarzałem ten sam zabieg z saszetkami jaki zaobserwowałem, kilka miesięcy wcześniej, w interwencji Wojtka. Moja praca przynosiła efekty, zgodnie z oczekiwaniami.

Kilku dorosłych skarżyło się na niezwykłe osłabienie organizmu i zwróciło się do mnie po lekarstwo. Będąc “kucykiem medycznym jednego czynu” (one act pony),, zastosowałem “leczenie saszetkami” i zaleciłem picie czystej wody mając nadzieje, że moja kuracja pomoże i że na pewno nie zaszkodzi.

Moja „interwencja medyczna” tu też zadziałała.

39.

Tym razem jednak nie zaoferowano nam żadnego kurczaka w geście wdzięczności. Co więcej, nie było żadnych widocznych oznak zadowolenia na twarzach matek.

A przecież musiały być uszczęśliwione „wskrzeszeniem” ich dziecka. Ich reakcja wydala mi się być kulturowo instruowanym aktem „wypierania naturalnych odruchów” w kontaktach, albo z mężczyzną (miałem wypielęgnowaną brodę), albo z jakimkolwiek mężczyzną napotkanym na drodze.

No cóż… musiałbym zostać dłużej, aby wymyślić wyjaśnienie tej “chłodnej” reakcji na leczenie, które, nadal mnie wzruszało prostota i skutecznością interwencji.

Antropologia wyjaśniła, że ludzie mają tendencję do wypowiadania czegoś takiego jak “dziękuję” tylko wtedy, gdy otrzymują coś nieoczekiwanego. Jako reakcję na niespodziankę. Jeśli otrzymują coś, co uważają za “oczywiste”, to będąc wiernymi swojemu kulturowemu „ja”, nie generują żadnych oznak radości.

Ta obserwacja podpada pod analizę fenomenu „podarunku”. A dokładniej, w jakich okolicznościach podarek (gift) wzbudza radość i „wzmożenie emocjonalne”, a w jakich nie robi większego wrażenia. Może nawet tłamsić emocje.

Prezent, choćby najwartościowszy, ale darowany nie w porę może wywołać reakcje odwrotną od zamierzonej.

Co on , ten obdarowujący, chce od nas w zamian? Pytamy się rezolutnie.

Przecie wiadomo, że „nie ma bezinteresownego lanczu” (no free lunches).

Z jednym wyjątkiem – mówią cynicy. Serek w pułapce na myszy jest ofiarowywany gratis.

Ekonomiści twierdzą, że ludzie “podnoszą swój poziomi szczęścia” za zarabianie/otrzymywanie pieniędzy do pewnego, przewidywalnego poziomu. Mają w takich sytuacjach element niepewności i miłego zaskoczenia. Wszystkie przychody powyżej tego progu nie robią pozytywnego wrażenia.

Nuda. Wszystko już było.