The Genealogical Tree and the Chronicle of the Polish Markowski Family, patiently written for children …

Chapter One

Great-great-grandparents

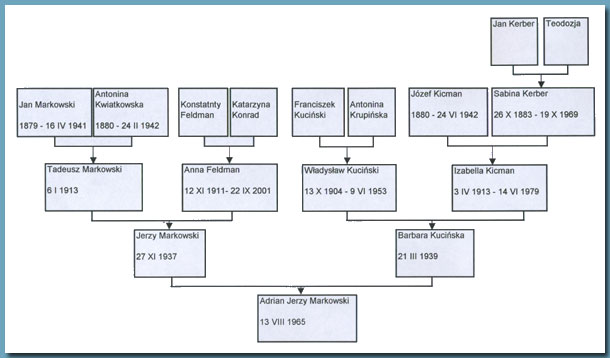

The history described in the pages of this Chronicle does not go far – only four generations back. We know about almost all the parents of your great-great-grandparents that they were there, and this obviousness must suffice for all of their inheritance. Two world wars and unreliable human memory meant that, after some ground, we can only reach the last years of the nineteenth century. As we take a step backward, we will inevitably find a void that we will never be able to fill with living forms. So the story can only start with your great-great-grandparents. Jan Markowski and Antonina née Kwiatkowska (great-great-grandparents) – Tadeusz Markowski (great-grandfather) – Jerzy Markowski (grandfather) – Adrian Markowski (dad) Like all your great-great-grandparents, Jan and Antonina Markowski belong to the generation that was born at the end of the 19th century.

Jan Markowski was born in 1879, and died at the age of 62 on April 16, 1941. His wife, Antonina née Kwiatkowska, born in 1880, died on February 24, 1942, so also at the age of 62. Where they were born, no we are sure. They had to spend several years in Silesia, because their son (your great-grandfather Tadeusz) was born in 1913, in the town of Niwka, near Sosnowiec (in the then Kingdom of Poland under Russian rule). In the early 1920s, maybe a little earlier they settled in Warsaw.

Great-great-grandfather Jan was a worker working on the railway, then known as the iron railway. He belonged to the Polish Socialist Party – Left. However, he was certainly not a quite common man, since in 1905 in Warsaw he ventured to take part in an attack on some unknown tsarist policymaker. His great-great-grandfather spent the next four years, first in the Warsaw Citadel, and then in the prison in Piotrków Trybunalski. Jan Markowski owed the sentence for an act of this category, probably not high, to the fact that his role was limited to bringing the bombers in a carriage to the vicinity of the Kierbedź Bridge and – as you can easily guess – an unsuccessful attempt to escape from the pursuit.

Great-great-grandfather Jan is also distinguished by the fact that for him in the whole family, the fight for independence brought tangible benefits. After 1918, he received a medal along with a decent, as his great-grandfather Tadeusz recalls, a lifetime salary.

The details of the attack, known to us thanks to Tadeusz’s great-grandfather’s account, may raise some reservations. Those who read with attention noticed that the attack was to take place in Warsaw several years before Niwka’s great-great-grandparents left. The earliest memories of Tadeusz’s great-grandfather come from Warsaw, which means that Jan and Antonina had to move there between his birth (1913), and the time when he entered primary school (around 1920). It can be concluded that the great-great-grandparents initially lived in Warsaw and only after Jan returned from prison (around 1909) they moved to the vicinity of Sosnowiec, from where they returned after Poland regained independence.

As for Jan’s wife, Antonina née Kwiatkowska, we only know that she raised five children. The great-grandfather’s house was definitely not overflowing, and Antonina made efforts to add something to the aforementioned salary and low wages. She was able to bring up children with work that involved washing and cleaning in nearby houses.

At least, together with Jan, she shaped the character of Tadeusz’s great-grandfather in such a way that there will be more to tell about.

The grave of Jan and Antonina is located in the Bródno cemetery in Warsaw. When I started writing, I didn’t know it existed at all. I visited her for the first time in my life on All Saints Day 1996.

Konstanty Feldman and Katarzyna née Konrad (great-great-grandparents) – Anna Markowska née Feldman (great-grandmother) – Jerzy Markowski (grandfather) – Adrian Markowski (dad)

The next story will take up little space and will be more guesswork than dates and facts. Konstanty and Katarzyna Feldman née Konrad are remembered so much that their hometown was Królewiec, and at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s they lived in Soczewka near Płock. The surname, which sounds in German, seems to confirm what was said about Königsberg. God only knows what winds brought them to the Vistula. Konstanty Feldman had to be born more or less at the same time as Jan Markowski, because when the latter found himself in the Warsaw Citadel as a result of the previously described events, Ania’s great-grandmother’s father was in the Crimea, and then traveled for a long time as a soldier of the tsarist army during the Japanese war. He had to experience and see a lot, because it was enough for long stories, which for a few years old Ania seemed like fairy tales. If anything more certain about Konstanty and Katarzyna can be inferred, it is only that their house was certainly not among the rich, as great-grandmother Ania had to start working at the age of sixteen and did not even graduate from elementary school.

We know little about their death. Katarzyna (probably much younger than Konstanty), after her husband’s death, moved to Lviv sometime in the 1950s. Supposedly enchanted by Konstanty’s memories, she saw in settling down across the eastern border promising the best prospects. Perhaps there would be nothing extraordinary about it, if not for the fact that the thing happened in the times of Stalinism. This undertaking cannot be explained in any reasonable way. Let us stop at the statement that Konstanty seems to remember the power of Russia until the end of his days, while Catherine parted with her life in Lviv, having probably thoroughly learned how the obvious delusion of memories from half a century ago may deviate from the reality in which one has to live, having made a mistake. If only the next generations would not have to pay for it! Because you have to add that Katarzyna did not move to the eastern border alone. She persuaded her grandmother’s sister Ania and her husband to do this, who took two daughters and a son with them! Your distant relatives still live somewhere in Lviv.

Franciszek Kuciński and Antonina née Krupińska (great-great-grandparents) – Władysław Kuciński (great-grandfather) – Barbara Markowska née Kucińska (grandmother) – Adrian Markowski (dad)

The story of my mother’s father, Władysław Kuciński, is quite interesting. Franciszek and Antonina née Krupińska, at the beginning of the century, lived in the village of Kuflew near Mińsk Mazowiecki and with their presence they changed the fate of some of its inhabitants so much that for some time one of the streets there was supposedly named after Franciszek Kuciński.

Francis came from the nobility. His son, Władysław, also admitted to having a coat of arms. It was even sketched by my mother, who, being a small child at the time, unfortunately did not remember the shapes of the drawing. It could have been the coat of arms of the Masovian Kuciński family – Ogończyk, but it is difficult to be sure.

Even during Franciszek’s lifetime, this coat of arms had no meaning, because the great-great-grandfather was the nobility only in name – he had no property, and the only hope for improving his fortune was from betting on the tsarist lottery. Strangely enough, he did not miscalculate at all and in the first years of the 20th century he won such a large sum that not only did he and his wife move to Russia for his fortune, but also from among his neighbors he took anyone who only wanted to go with him. In this way, thanks to Franciszek Kuciński, the population of the village changed dramatically, a fact that was celebrated by posterity by naming one of the streets with his name. What, like what, but great-great-grandfather’s fantasy cannot be denied!

Today, of course, you will not find Kuciński Street in Kuflewo. While writing these pages, in August 1995 I called the parish, where the only telephone in the village was installed. The local priest explained to me that the streets in Kuflewo have long been gone. Houses are marked with numbers. Once upon a time, Kuflew was a town, but it lost its town charter shortly after 1863, which was a punishment for its inhabitants’ participation in the January Uprising. The streets with names still existed for several dozen years, but they naturally disappeared as the population declined. It is also difficult to obtain any documents, because most of them, including the old parish books, were lost during the last war. So, apart from what is left in human memory and a few three-ruble notes, which are to be mentioned, there is no trace of the great-grandfather’s exploits.

On his journey, the aim of which was to multiply the already decent money, Francis traveled far, as far as Irkutsk. It is true that he hated the climate there, because in his memories he quite often cursed the frost, which caused that after spitting, not saliva, but a lump of ice fell to the ground. However, he achieved his goal, becoming a very rich man. It can be assumed that bakeries were the source of the great-grandfather’s wealth.

The story of the great-great-grandfather does not have a happy ending. His property was lost shortly before the outbreak of World War I, or perhaps a Bolshevik coup. It happened thanks to Antonina, who, for reasons that cannot be understood today, exchanged gold for cash. The obvious result of the operation was that they were both soon able to enjoy the sight of a very large number of banknotes, admittedly nice, but now quite worthless.

Today it is in vain to find out about the details of my great-great-grandmother’s actions, having no idea about the then ways of investing capital. However, it is possible to suspect that, among other things, she paid an incredible sum from the bank with the intention of keeping it under the pillow. It seems all the more certain that some of the money survived the next half a century, and as a child I could see several hundred at least three-ruble banknotes from 1905, lying in a drawer of my grandmother’s wardrobe (my great-great-grandparents had to bring them to Poland in 1922).

Franciszek, as far as we know, died somewhere on the threshold of the 1930s. His graves are probably to be found in Mińsk Mazowiecki, where he spent the last years of his life. Antonina broke up with life in the early 1960s, that is, shortly before my birth. Her grave is located in the Ursus cemetery.

One thing needs to be said for the defense of her great-great-grandmother: on October 13, 1904 in Irkutsk, she gave birth to twins, who were given the names Franciszek and Władysław. The latter, about which there will be more to say, in 1922 he returned with his parents to Poland and settled in Warsaw. He is your great-grandfather.

Józef Kicman and Sabina née Kerber (great-great-grandparents) – Izabella Kucińska née Kicman (great-grandmother) – Barbara Markowska née Kucińska (grandmother) – Adrian Markowski (dad)

It seems that somehow more remains after the male lines, because the parents of your great-grandmother, Izabella Kucińska née Kicman, are known more or less as about the Feldmans. The strange sounding and rare surname Kicman says nothing about its origin (in the mid-nineties, it was worn by only two hundred people in Poland). Józef Kicman and Sabina Maria née Kerber had an estate near Legionowo. What its name was, and where it could be approximately, will remain a mystery forever. The only thing that remains in the memory of posterity is that the name of the property contained the word Góra, but this also seems not entirely certain.

From the only document about the Kicmans, preserved to this day, we learn that Sabina’s parents were named Jan and Teodosia (these are the only great-great-grandparents whose names we know), while her great-great-grandmother was born on October 26, 1883, and died on October 19, 1969 in Warsaw. , where she lived in a two-story house belonging to the Kicman family at 12 Liwska Street.

From the inscription on the grave of his great-great-grandparents, at the Bródno cemetery, you can also learn that Józef died on June 24, 1942, at the age of 62, so he had to be born in 1880. The last information we can give about the Kicmans is the fact that that at the beginning of the century they ended up in Kharkiv in an inexplicable way, where your great-grandmother Izabella was born on April 3, 1913.

(In the place where the Kicmans tenement house were, there are now blocks of the Bródno estate. Perhaps the trial, which began in the late 1990s, will one day lead to the fact that the heirs of Jan and Theodosia, including my mother, will receive compensation for the house at Liwska taken away by the state. 12.)

Unfortunately, it will end here, although I could learn about my great-great-grandparents from the very source, because great-grandmother Izabella lived with me and my parents until 1979 and her mind was clear until the last moments. Well, I could not have foreseen then that one day I would investigate my family history. I was only 13 at the time of her death.

Chapter two

Great-grandparents

God disposed of the fate of the families described in such a way that in the next generation, the children derived from them joined into marriages, which resulted in the birth of your grandparents, and then parents.

The son of Jan and Antonina Markowski, Tadeusz married Anna, daughter of the Feldmans (Konstanty and Katarzyna), and Władysław Kuciński (son of Franciszek and Antonina) married Izabella Kicman (daughter of Józef and Sabina). The chain of events that leads to the birth of a human being is strange!

Tadeusz Markowski and Anna née Feldman (great-grandparents) – Jerzy Markowski (grandfather) – Adrian Markowski (dad)

Let’s start with Tadeusz Markowski, whose story has the priceless advantage of being recorded in writing, in a kind of diary from which you can easily learn about his life. Almost everything that has already been said about Markowski’s great-great-grandparents comes from this source, and now, thanks to the diary, it will be possible to go to stories about the fate of the great-grandfather himself, from his childhood to the post-war years.

Great-grandfather Tadeusz was born on January 6, 1913 in the aforementioned Niwka near Sosnowiec. His earliest memories, however, come from Warsaw, from a house at ul. Przyokopowa 3. He grew up in the yard of a tenement house and, together with four siblings, traveled the four kilometers that divided Przyokopowa Street from Łucka Street, where a primary school was located. Besides, probably none of Jan and Antonina’s children graduated from this school, which was the result of the most obvious poverty. This poverty must have been really severe, since the great-great-grandfather’s offspring started working at the age of a dozen or so.

It is difficult to blame a man with an education of less than seven classes for the fact that he took up classes which could not, by any means, beat him above the mediocrity. Great-grandfather worked as a bricklayer assistant, carpenter, he was a worker in the Wedel factory, and finally, after the war, he got involved in the construction of the Warsaw metro and finally at geological works. If he had stopped there, there would be nothing to write home about. Fortunately, his life was completely different, which took him to such places where mediocrity cannot be talked about. His passion was practicing the sport known before the war as French fights, that is, today’s wrestling.

He started his great-grandfather in 1932 in the Warsaw Legia, winning second place in the Warsaw Championships. In the mid-1930s, he changed the club, moving to Rywal, founded by Emil Wedel, the owner of the Chocolate Factory. In the colors of this club, in 1935 he first won the title of the Champion of Warsaw, and then the Polish Vice-Champion, and this double success was repeated in 1938. Strangely enough, after the war, which meant almost six years of hard work for him, he did not lose his tone. . In the early 1950s, he once again stood on the podium in the Warsaw Championships and the Polish Championships, winning the same titles as before. Pre-war human format! More will be said soon.

In the fall of 1935, Tadeusz was drafted into the army. The beginnings of his service in the 8th Light Artillery Regiment in Płock seem difficult, but from what he writes it can be obviously concluded that he considered his duty towards his homeland (written with a capital letter) to be sacred. This is the first lesson in pre-war thinking, because the Motherland did not spoil neither my great-grandfather nor his relatives.

During the passes, my great-grandfather used to go to the park on Góra Tumska. He looked at the castle, the Vistula flowing downstream, and for the first time in his life he was probably thinking about history. It was in this park that one evening one of the walking girls caught his attention. It was Anna Feldman, his future wife, my father’s mother.

Anna Feldman was born on November 12, 1911, so when she met her future husband, she was 24. Like him, deprived of education, she worked in one of the factories in Płock. When her great-grandfather Tadeusz finished his military service, at the end of 1936, she left with him to Warsaw and, thanks to the acquaintance of her fiancé, she immediately got a job with Wedel. They got married on August 15, 1937, and on November 27, Anna gave birth to the first of her three children, my father, Jerzy.

My great-grandparents led a peaceful and prosperous life until August 24, 1939. On that day, Tadeusz received a mobilization card, obliging him to appear within 48 hours in Zajezierze near Dęblin, where the 28th Light Artillery Regiment was located. After saying goodbye to his family, he boarded the train at the Warszawa Wschodnia station, not realizing that most of the people saying goodbye to him would only come in six years, and that he would see his parents for the last time.

The short, September history of the 28th Light Artillery Regiment can be summarized in a few sentences. In the last days of August, the regiment reached Wieluń, and then Praszka. He stayed there until September 3 and began his retreat towards Warsaw. For three days he defended himself near Łódź, then with the last of his strength he dragged himself to Błonie, where on September 12 he was surrounded and almost taken prisoner. Indeed, a short story, so unfortunately typical of that tragic autumn.

Great-grandfather marched in a column of prisoners. It is hard to believe, but the diary shows unequivocally that his thoughts focused more on military matters than on the uncertain day tomorrow. He put on his uniform to defend his homeland. He did not defend her because he could not, but he could not easily suppress his bitterness. In order to understand the essence of things, it is enough to quote only one sentence from the diary, in which my great-grandfather literally states that during his retreat from the border he felt “an enemy of his own nation”. Nothing more nothing less. The next lesson of pre-war thinking, and not the last one.

Someone may be ready to take the words of great-grandfather as evidence of naivety or even blindness to the real balance of forces. Nothing could be more wrong! The hopelessness of the situation he realized, he saw the advantage of the enemy. But then there were also such things that no calculations wanted to make, and which were at a higher fixed price than human life. Recent times, and the ground over them has been trampled so strongly that hardly anyone remembers what lessons can be learned from them …

The prisoners were taken to Mszczonów. Here my great-grandfather brushed against death, and to be more precise, he fled from it, jumping over the church wall, behind which the captured were crowded for the night. It was like this: in the evening the Germans, when searching prisoners, not for the first time, found a razor in their great-grandfather’s pocket. He had been allowed to keep her previously, so apparently he shouldn’t have been worried. This time, however, along with two other unfortunates, he was dragged aside, led out into the field, just outside the church wall, and soon he was handed a shovel, which under the circumstances made the situation quite clear.

Great-grandfather was digging his own grave, as anyone in his place would, slowly and without enthusiasm. At the same time, he was frantically looking for a way to save his skin. It was a difficult task, because a man paralyzed with fear for his own life will not be able to think up a lot and do… unless he has something more worthwhile to his sleeve. The Second Polish Republic and the service in its army equipped my great-grandfather with this kind of weapon. He shook himself at the thought of a soldier’s honor, which was somehow incompatible with making his own grave in front of the enemy. He quickly abandoned the consideration of a flight into the field, because it could bring the most worthy death, but in no case salvation, and chose the second option, as obvious to him as it was surprising for the firing squad standing by the wall. When the soldiers let him out of sight for a moment, he jumped on them, smashed him, he broke the wall and fell into the crowd of prisoners on the other side. He still had the strength to hide in the church choir and get rid of what might have betrayed him if the Germans had risen to the chase. He got rid of the two golden teeth that were visible every time he opened his mouth. He just knocked them out with whatever he had at hand. It begs to say a word again about the pre-war school!

From Mszczonów the prisoners were led through Rawa Mazowiecka to Częstochowa, from where they were transported by train to Austria in September. Then, in October, they went to Magdeburg, to Stalag XI A.

His great-grandfather spent five years as slave labor in German fields, first in the vicinity of Magdeburg, and later in Dessau. Considering the circumstances, the fate is not the worst, although it is difficult to know whether the awareness that it is sometimes much worse may desensitize a person to hunger, lice bites and cattle work. Her great-grandfather did not seem to be anesthetized, because in the end he made a completely hopeless attempt to escape under these conditions.

He didn’t necessarily get very far. He was already captured in Dessau and sent to the quarries of the penal camp in Austria, where he quickly realized that so far the Third Reich had bestowed only favors on him. After three months, exhausted to the limit, he was ready to become a lifelong cripple, if only he would return to work in the fields.

This is where an unusual story begins, because it concerns a prophetic dream. As it was said, in order to leave the camp, my great-grandfather intended to sacrifice the remnants of his own health. He did not try to think about escaping, and he could clearly see the fact that he would not be able to bring life out of the quarries. Fortunately, German law made it possible to release prisoners. It was enough for them to be declared unfit for work. In a time and place-specific interpretation, this rule meant getting rid of those who had lost at least an arm or a leg.

Great-grandfather chose the loss of a leg as the lesser evil and decided to put it under one of the wagons used to transport stones. Prisoners pushed these wagons on the rails, so the misfortune could have happened with just any stumble. Simplicity and cool calculation … just like a few years earlier by the church wall in Mszczonów. My great-grandfather was stopped from his desperate step… by a dream.

The night before the planned accident, he dreamed that he would be released from the camp. Whether he believed in the fulfillment of this dream is rather doubtful, but the fact is that the next day he did not decide to put his foot under the wheels. And he did very well, because as if against his own common sense, the dream was true to the letter on the same afternoon! Let me not look for fancy terms and name this event simply – a miracle.

This is where the most interesting chapter of great-grandfather history ends. The year 1945 found him in the very same fields from which he had previously fled. When the Soviet army approached, without thinking he got on the cart with other Poles and pulled towards Warsaw. He was brought to the destroyed city by a Soviet freight train, in which he somehow managed to hide at the border.

At this point, it is necessary to describe a scene that is perhaps not very important, but appeals to the imagination. The train passed through Warsaw. His great-grandfather jumped out of it across the Vistula River, near the Zoological Garden. After six long years, he was back in his city, which he remembered for what it was in August 1939, when he was saying goodbye to his family at the Eastern Railway Station. For a long time he stood on the railway embankment, tearfully staring at the ruins and wondering if any of those who waited for his return could survive in the ruins. The end of the description of an unimportant scene, which somehow strangely engraved in my memory, that while writing these words I have it before my eyes as if I were a witness to it and it seems to me that I feel a breeze by the Vistula river that welcomed my great-grandfather Tadeusz on the Praga bank. But it’s time to return to historical prose.

The great-grandfather was one of the lucky ones who easily found their loved ones. On the same day, he greeted his siblings, and the next morning he left for Płock, to Soczewka, where his wife and son were waiting for him. Only the parents who died during the occupation were missing.

He did not have to start his professional life anew. A place was waiting for him in the Wedel Factory. However, he did not stay there long. Soon he sensed the incredible possibilities inherent in trading and turned to it with a passion that could only be compared to the one that earned him championship titles in wrestling. He traded whatever he could, and as the times were dreamlike, the family enjoyed plenty of wealth for a few years, the source of which was the shop run together with his sister at the Różycki Bazaar. The idyll ended in 1950 with the addition of tax surplus to the store, which forced my great-grandfather to look for another job. He got a job at the construction site of the Warsaw metro, and after he quit, he learned the profession, he drilled wells in various parts of Poland, taking his son and my father with him during the holidays,

Today, my great-grandfather Tadeusz, for a man over ninety, is so sticky that God forbid everyone. Something of the old vigor remained in him, until recently a passion for trade was sometimes felt. You see him often, so it will remain in your memory … what more can you tell?

Władysław Kuciński (great-grandfather) – Barbara Markowska née Kucińska (grandmother) – Adrian Markowski (father)

Great-grandfather Władysław Kuciński, father of Basia’s grandmother, would probably share the fate of many characters described in this script, about whom they were not known and what their lives were they tried to find out everything and write it down. The circumstance was really tragic, because these people were the investigators of the Public Security Office, who did not want to perpetuate the memory of their great-grandfather, but only to bring him to the grave as soon as possible. However, it is appropriate to start all over again.

Great-grandfather Władysław was born on October 13, 1904, in distant Irkutsk. It is far from everything we know, beyond the Urals, the great Siberian rivers of Ob and Yenisei, where the Angara begins in Baikal. He came into the world as one of the twins to be mentioned, describing the story of their noble-minded father, Franciszek and mother, Antonina, who preferred to keep money under her pillow. In Irkutsk, he also obtained some education that is difficult to define today. Disputes on this matter are confusing, because in the files themselves you can find at least two different versions, and in addition, my great-grandfather writes something completely different in his biography from 1949. So let us stop at the fact that his education was most likely between primary and secondary school.

It is also known about these times that before leaving for Poland, he worked a year as a telegraph operator at a railway station in Irkutsk or a nearby one. Different from those who were born on the Vistula River, Siberian childhood must have shaped his character. Soon you will have to convince yourself of it.

Władysław saw Poland only in 1922, when Franciszek and Antonina decided to return to their homeland. It must have been a long jump for an eighteen-year-old boy raised by Lake Baikal. For the first time he saw his homeland, which he must have known from stories, for the first time he heard Polish speech in the street. Having found himself in Warsaw, he and his parents lived at 6 Długa Street. It should be added that despite the recent financial catastrophe, Franciszek and Antonina did not do too badly, since, according to one of the MBP notes, Władysław’s father had his own enterprise. It was probably not too big, because in his biography his great-grandfather describes his family as craftsman’s family, although one should take the correction that after the war, different things were written in the biographies. But it looks like We can describe the entire next three decades of our great-grandfather’s life with just a few dry facts. Władysław graduated from a technical school. In the years 1925-27 he served in the 21st Lancers Regiment in Równe, where he received the rank of corporal, and after taking off his uniform, he started working at the Office of Intercity Telephones and Telegraphs at 45 Nowogrodzka Street.On October 27, 1936, he married Izabella Kicman, daughter of Józef and Sabina Kicmanów. So many dry facts, almost written down from yellowed pages.

A sudden and tragic turn in his great-grandfather’s biography took place exactly at 10.30 a.m. on December 17, 1952. Władysław was already then the head of the technical department in the Directorate of the Warsaw Telecommunications District, based in the same building on Nowogrodzka Street, where he had started work over twenty years earlier. It was on that winter morning that a fire broke out in the telephone exchange adjacent to the offices. It was absolutely no cataclysm, it just burned down one of the pieces of equipment, which could happen that most of its parts were preserved with kerosene and were in the vicinity of electric sparks during operation.

The fire was extinguished immediately, the damage was repaired within a few days, and the case would have been forgotten, if not for the informant pseudonym “Ryś” not installed among the employees, who promptly reported everything about the security services. As you can guess, it was a sufficient excuse for the security service to initiate an investigation, which within a week or so, for some reason, focused on the person of my great-grandfather. He was arrested the night before Christmas Eve 1952.

Initially, the accusations against Władysław focused on the idea that he personally started a fire, which was given the threateningly sounding name of sabotage. This absurd accusation could not be proved by any means, because on the basis of the testimonies it was only possible to put forward against the great-grandfather that, seeing people putting out the fire, he stepped aside and somehow took his time to help. He must have sensed what was going to happen, because when asked the next day by one of the employees, he directly stated that he preferred to stay away, because “he does not want to deal with the authorities”.

After nearly six months of investigation, it was found that Władysław did not commit the sabotage, but the fire did not start on its own, so the cause of the accident should be considered to be his great-grandfather’s negligence in the performance of managerial duties. The case was quickly referred to the Special Commission for Combating Abuses and Economic Harm, which immediately sentenced him to twenty-four months of hard labor. This sentence was to be served by my great-grandfather in the labor camp at Anielewicza Street in Warsaw. To remain true to the facts, it should be added that the sentence was soon lightened to eighteen and then nine months, which, however, was of no importance to Władysław. He died in the prison hospital at 26 Anielewicza Street, on June 9, 1953, three days after

Actually, the story of Władysław Kuciński could end here, but it is hindered by at least two questions, to which there is no answer in the files. First of all, we learn from the documents that, apart from my great-grandfather, two employees of the headquarters were detained, one of whom at the end of the 1940s aroused the interest of the Kielce security service. So why were the accusations made almost immediately against a director who was least actually related to the accident? Second: Why the sudden death just a few days after the final sentence is passed? Great-grandmother Izabella, who visited her husband in the first days of June, found him completely healthy, while the death certificate stated chronic tuberculosis as the cause of death. These circumstances look too suspicious to pass over to the agenda.

So let’s quote my mother’s memories, which seem to throw a whole new light on the matter.

At the time of her father’s death, my grandmother Basia was only fourteen years old. No wonder that great-grandmother Izabella did not let her know the details of the family tragedy at the time. Much more puzzling is the fact that she has never done it, and as a result, all my mother’s messages come only from friends, that is, from the second, third, or any other hand.

According to this version of events, both the arrest and death of Władysław were, in a way, an obvious result of the implementation of the commission entrusted to him, which concerned the preparation of a telephone network connection project for the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party. As a result, the great-grandfather was on the list of those uncomfortable people who, at that time, had too extensive knowledge to be left alive. In the case of Władysław, the Ministry of Public Security had an easier situation, because my great-grandfather was not a humble person, he used to express his opinion aloud, which in itself made him a potential victim.

The files are full of information that Władysław did not say, in public and in private conversations, which definitely could not win him the sympathy of the people who tried to establish themselves in the people’s state. Among other things, in 1951 he caused quite a stir at the founding trade union meeting, declaring that neither the idea nor the people involved in its implementation inspire his trust in the slightest. He was evidently a rare man at that time, who thought and spoke, and naturally he did not take it as a sin. So much for the causes of the great-grandfather’s tragedy. As for its course, my mother’s version adds only one fact to what has already been said, namely that Władysław was murdered in the prison hospital by some kind of injection. The description seems to be credible because it comes from a nurse who worked in the hospital at Anielewicza Street at the time. Thanks to this nurse, also great-grandmother Izabella learned about her husband’s death.

That’s all I have learned about my great-grandfather’s case, and it does not seem that the matter will ever be fully clarified. It is a fact that my mother’s version of the events seems very probable, but there are also significant ambiguities in it. effort to create two volumes of files, full testimonies and detailed technical expertise. If Władysław really belonged to the category of people to be removed, his hearing would be lost, and that’s it. Everything seems to indicate that at some decisive moment, the course of events was decided not so much by man as by chance.

Izabella Kucińska née Kicman (great-grandmother) – Barbara Markowska née Kucińska (grandmother) – Adrian Markowski (dad)

It is quite apparent a paradox that I know infinitely more about my great-grandfather Władysław, whom I have never seen before my eyes than about his wife, that is, my grandmother, with whom I shared an apartment until 1979. This is what a thing written on paper means. If your great-grandmother left something more than one, half a page with a curriculum vitae and a few school reports …

Izabella Kucińska, née Kicman, by a strange twist of fate, she had in common with her husband, among others, that she was born in Russia. It is true that the road from Kharkiv, located just behind the Dnieper, to Warsaw cannot be compared with the enormity of the space that separates Kharkiv from Irkutsk. However, no matter how he looked, it was also under the tsar’s rule, so the analogy seems justified. As I have already mentioned, God only knows where Józef and Sabina Kicman came from in the eastern borderlands of Ukraine and how they returned to the Vistula. It is certain, however, that their return took place in 1920, i.e. about two years before Władysław Kuciński’s family settled in Warsaw.

Izabella’s parents did not seem to be the poorest people, which I did not dare to conclude when I inquired about the real or non-existent property. It is difficult to be certain in this matter, but the assumption seems to be correct, since they could afford to educate their great-grandmothers at the Gymnasium for them. Klementyna from Tańska Hoffmanowa and the Natalia Zarodzińska Music School in Prague.

In her curriculum vitae dated 1950, the great-grandmother mentions only the Zuzanna Rabska. However, I do not have too much confidence in this knowledge, as no certificate has survived from this school, quite contrary to the testimonies from the gymnasium which was not mentioned in the same biography. It seems a similar case to the aforementioned biography of Władysław Kuciński, which – written a year earlier – also left a lot of ambiguity. Today, such extreme caution may seem excessive, but it was seen differently at the time. As for the property status of the Kicmans, it is worth adding that the great-grandmother had several sisters who were not less well-educated. I will not mention the tenement house.

In 1934, as a twenty-one-year-old girl, Izabella started working at the Telecommunications Office – the same where Władysław Kuciński had been working for probably seven years. One can freely risk a claim that this is where the meeting of my great-grandparents took place. Two years later, as a married couple, Izabella and Władysław rented a flat at 3 Parkowa Street (today Cietrzewia Street), in Włochy, where you can visit your grandmother and grandfather to this day, and where I spent the first thirty almost years of my life.

Before the war, my great-grandparents were doing very well. The great-grandmother could quit her job and devote herself to running the house. Even today, the phrase that the hand of an official entered in her ID card, in the profession field: “by my husband”, seems unusual. They somehow survived the war as well, although wedding rings were sold, and at least at one point my mother and her two sisters were close to being orphans. One of the apartments in the house at 3 Parkowa Street was designated as a quarters for SS officers from Aleja Szucha. This news reached the great-grandparents so little in advance that Władysław barely had time to take the grenades from the apartment, the later famous insurgent “Sidolówki”, in the production and distribution of which Izabella took part. In his haste, he buried them in the garden; The following anecdote from the time of the occupation testifies to the great-grandmother’s strong nerves, at least when it comes to grenades: it is evening, great-grandmother bathes the children before bedtime. A friend rolls into the apartment with a huge suitcase (what a friend, it is not known, at least she lived with her great-grandparents for some time). The friend sits down comfortably, starts rummaging in the contents of the suitcase (from where she brought her things, it has also not survived) and at one point she turns to her great-grandmother, showing a small object:

– Look, Mrs. Kucińska, what a strange bottle of perfume – and then she starts to grapple with the cap.

The great-grandmother raises her head from the tub in which her daughters are splashing and says in a resolute tone:

– Please put this away, please. Please put this on the table.

A slightly surprised woman puts the item aside.

Only now does my great-grandmother take a deep breath.

“This is a grenade,” he says, checking that the pin remains in place and goes back to bathing the children.

The great-grandmother did not only deal with grenades. Working on behalf of the commander of the Home Army, Warsaw-Wola also undertook intelligence and sabotage actions. In any case, unlike Władysław, who focused on caring for the home and children, Izabella was a man with unbreakable nerves and apparently maddened courage. The above information comes from a person with whom your grandparents have family relations and whom I am used to seeing as my aunt, although there is no relationship between us. We are talking about aunt Mela Wolska, who during the occupation lived in a house at 3 Parkowa Street. She is the sister of the aforementioned commander of the Home Army and a lecturer in the underground cadet school. During the occupation, he was known under various pseudonyms. His real name was Dziubiński. He did not survive the war. Whether an acquaintance suffered a heart attack, it is not known, and when it comes to great-grandmother, an observation that has already been repeated many times is on the lips – the pre-war format of a man was!

The post-war course of events is not difficult to predict, knowing the history of Władysław. At the age of forty, my great-grandmother was left alone with three daughters. There was no husband, father and the only person whose work has so far provided Izabella and the children with a reasonably good life. It is true that it may be presumed that in the early 1950s the pre-war prosperity in my great-grandmother’s house was only a memory, but the lonely support of three daughters, the eldest of whom was slightly more than ten years old, must have meant poverty. Not so long ago, Grandma Basia showed me the remains of the only doll she had in her childhood to play with her sisters, pulled from somewhere at the bottom of the wardrobe. In 1961, Izabella experienced another tragedy. During a trip to Masuria, her youngest daughter, 17-year-old Małgorzata, drowned.

This is roughly all I know about Izabella’s great-grandmother. In my memories he appears as a person of strict morals, basic views and a tough character. I also remember her as a devout Catholic; it was she who, when I was a child of only a few years, took me to Sunday masses to the Church of Our Lady of La Salette. She lived modestly from the retirement she had after years of working at the Telecommunications Office, to which she returned after the unfortunate year 1953. She never spoke of Władysław and his death, rarely about the occupation, and if she lost a word about the Home Army, she always warned lest I, God forbid, mention it outside the house. Her fears did not result only from the tragic experiences, in those days they were perfectly justified. She died on June 14, 1979 and, like Władysław and Małgorzata, was buried in the cemetery in Włochy. In 1984, another of her daughters, Alicja, who was my godmother, was buried there.

At this point, it is worth devoting some attention to certain coincidences, characteristic of Basia’s grandmother’s family. Grandma’s sisters – Małgorzata and Alicja, were born in June: Alicja – June 15, 1941, and Małgorzata on June 25, 1943. Władysław died on June 9, 1953, Małgorzata died on June 1, 1961 in Corpus Christi, Izabella – June 14, 1979, also at God Body. Out of all four, only Alicja died in a different month – October 14, 1984, the day after her father’s birthday. It is worth recalling here that Izabella’s great-grandmother Józef Kicman died on June 24, 1942, so one year and one day before the birth of his granddaughter – Małgorzata. For me, these are only dates, for Grandma Basia, however, these coincidences had a deeper meaning in the past, as a result of which for many years she was anxiously awaiting each subsequent June. By the way,

This is where it will end. I must admit with regret that in fact I cannot tell much about my great-grandmother Izabella, with whom my earliest years were associated more than with my parents. To this day, when I remember the street shaded by spreading chestnut trees, I can see a tall figure of my grandmother, in a coat, with a headscarf on her head, I can see her as she was when she accompanied me to my first lessons at school on warm autumn mornings.

Adrian M.