Family heirlooms – Poland – Memories of “Zakopane – before the war – uncle Jan Rzewnicki”

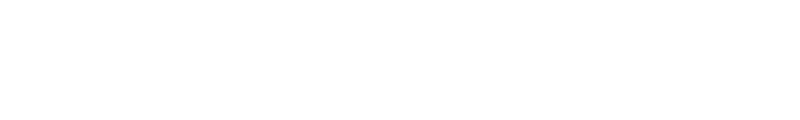

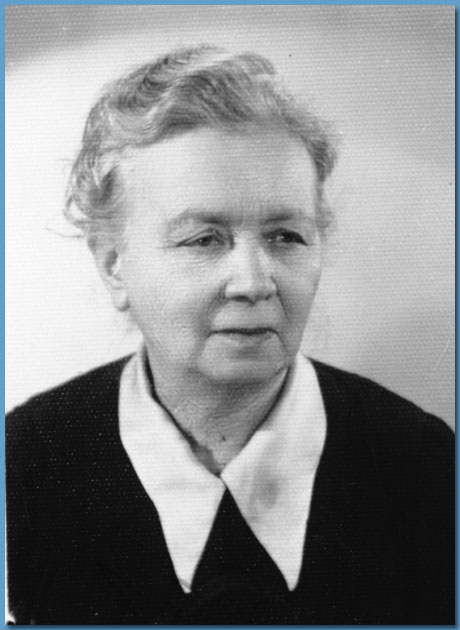

My uncle Jan Rzewnicki – a retired electrical engineer – was a passionate and well-known mountaineer in the 1920s and at the beginning of the 1930s, as well as the editor of the Wierchy magazine.

With his help, we got to know the Tatra Mountains: first my older sister Danuta, and then me. In 1932 – then I was almost 10 years old – I spent my winter holidays in Zakopane with my uncle Rzewnicki .. We lived in the guesthouse “Belweder” in Żywczańskie, which was owned by old Mrs. Tabeau, my mother’s distant cousin. Her daughter (unmarried, or maybe a widow, I don’t remember) helped with running the guesthouse.

With my uncle, “we went for long walks, we went sledding to the Kościeliska and Strążyska Valley. The trip to Morskie Oko was too long for a sledge. You took a taxi: the old-fashioned – probably still from the First World War – Austro-Daimler.

It was a large open car with a canvas shed. It could comfortably accommodate 9 people, including 3 on folding seats, the so-called strapontenes. It had a huge wooden steering wheel on the right-hand side, and a gearshift and handbrake on the outside of the body, also on the right-hand side. The driver and passengers had to be very warmly dressed, as the canvas canopy and celluloid lenses only symbolically protected against cold air streams.

The vehicle was moving quite vividly. I suppose it was over 60 km / h on straight sections. while making a lot of noise and shaking mercilessly. It had narrow, high-pressure tires and very hard springs, and the road to Morskie Oko was not of the best quality. There were several such taxis in Zakopane at the time. There were also large open-air old Tatras, but riding them was a much smaller fashion.

My uncle constantly organized some excursions (or rather walks, he was involved in climbing only in the summer). There were also attractive lunches in various nearby shelters. It was the first time I drank mulled wine to warm up after freezing during one of these kinds of trips, a bit too long for me.

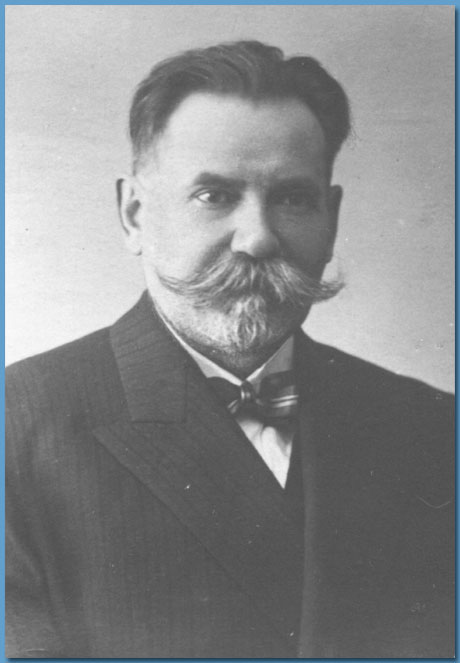

Aunt Jadwiga, who was very frugal (not to say stingy), tolerated her Uncle’s “antics” because the mountains were sacred to him. Although he was sitting hopelessly under Aunt’s slipper, he ruled in Zakopane alone (or maybe almost alone).

During my first stay in the mountains in winter, I learned to ski (on loan) a little. I coped quite well with the downhill “Na Lipkach” and from Regla. In the evenings, the Belvedere company played bridge; Uncle with the senior guard in preferansa. In general, I cheered, and sometimes even got cards in my hand when someone from the players left the table for a moment.

I liked going to Grandma Tabeau’s room in the evenings and listening to her stories about my mother’s family, which I had never known before, as well as the history of Galicia, which I did not know at all.

Unfortunately, all the details have long been forgotten by me. I only know that Grandma emphasized that the Tabeau family came to Poland with the court of Queen Marysieńka, and not in the times of Napoleon’s adventurer.

While I was in Zakopane, my sister fell ill with scarlet fever in Warsaw. So I couldn’t go home. Rzewniccy left, I stayed. For the first two or three days at the now empty Belvedere, where I was terribly bored without company, and then transferred to the house of Dr. Fischer, Grandma Tabeau’s son-in-law. He was a very popular doctor of pulmonary diseases, he had a beautiful apartment at Kościuszki Street, near Krupówki (in his own house, by the way). He lived with his wife and daughter Grażyna, a bit younger than me. Their two older children were in Krakow, they went to junior high school, and maybe already to college, I don’t remember.

Uncle was a Lvivian for several generations and so beautifully, even demonstratively, “drew” in Lviv that when I heard it for the first time, I was convinced that he was pretending to be the famous Mr. ). Meanwhile, it turned out that Uncle always says that.

I called him “Uncle”, although, as he explained it to me, our relationship was of the type: aunt aunt’s great-uncle.

In my aunt and uncle’s apartment there were large portraits of all family members painted by Witkacy. He was his Uncle’s patient and thus regulated the cost of his treatment.

I was given my uncle’s room (absent older son) at my uncle’s disposal. I remember that there was a library in it, and in it books from the “Library of knowledge” series. I have read them all. At home, my parents would not let me read in bed, except when I was ill. At my aunt and uncle’s house, no one was interested in what I do in the evening after the solemn good night.

They also didn’t really care about what I do during the day. The customs were completely different than in my family home. So we wandered with Grażyna – and it was the devil incarnate, not a girl – all day skiing. We just had to be on time for lunch and dinner. After the school holidays ended, Grażyna returned to school and we could ride together only in the afternoon. In the morning I traveled alone, or rather with a group of highlanders whom Grażyna met. I often came home wet to the skin. It did not make any impression on anyone. The effect of this stay in Zakopane was such that when I returned to Warsaw, it was difficult to get to know me. I grew a few centimeters, got very tired, and the period when I was a “meager, sickly child” is over.

The return trip to Warsaw stuck in my memory. My uncle put me in a second-class car (at that time the PKP carriages had three classes) and put me in the care of the conductor. In the compartment, an older man, who turned out to be a doctor, my father’s acquaintance, became interested in a lonely little brat. At that time, basically all Warsaw doctors knew each other, if not personally, then at least by hearing.

He was a bit surprised that I was going this far alone. He invited me to the restaurant car for lunch. It was the first time I was in such a running restaurant. After returning to the compartment, he borrowed radio headphones from the conductor. I and II class carriages in fast long-distance trains were radio-controlled. On the walls of the compartments there were sockets for headphones, which were borrowed from the conductor. The rental cost probably 2 zlotys, which was quite a lot. The headphones were delivered packed in a paper bag with an imprint that its contents had been disinfected.

In Warsaw, I got off at the still old Main Railway Station on the corner of Aleje Jerozolimskie and Marszałkowska. Following my parents’ instructions, I went home in a horse-drawn carriage from the train station. It was a time of crisis and long lines of taxis and horse-drawn carriages waited at the stops. The driver, seeing such a frivolous passenger, agreed to go for half the official fare.

Describing this detail, I recall a cartoon piece that I saw in a newspaper at that time: a passenger with a large suitcase approached the cab at the end of a very long line; the cab driver points out to him that, in accordance with the rules of the caboose savoir vivre, he can only be picked up by a cab at the beginning of the queue; so please give me a lift to the first one, I have a heavy suitcase – says the candidate for a passenger.

At home, I amazed my parents with my excellent physical condition – they changed my child – says Mom proudly. You have a good head for business, Father said when I told you how I had bargained for a carriage course. Here, unfortunately, he made a mistake, which is a pity.

I found a surprise at home: a tube radio. Radio on headphones, so-called detector, it has been with us for a long time, but we used it quite rarely. Now it was a real radio with a loudspeaker and two wavebands: a three-lamp Philips, assembled in Poland by the Borkowski Brothers company.

My sister was in college with Miss Borkowska and I think she was even friends with her. The radio was purchased “after acquaintance” at a special promotional price. It lasted until the beginning of the occupation. In October 1939, the Germans, threatening severe penalties, ordered the handing over of all kinds of radio receivers. The old Philips was put into “technical inspection”. It was made by an employee of the company Bracia Borkowscy, in which the receiver was once assembled. He guaranteed that after connecting to the network, after a dozen or so minutes, a short circuit would occur and the Germans g…. they will enjoy it.