A family memento – Poland – Memories of “All Souls’ Day 1939”

By chance, on my way back to Warsaw in the first days of October 1939, I met my high school friend and friend Olgierd Wilczewski, in my family and among friends called Dzidek. In July we were together on a successful bike trip in the Świętokrzyskie Mountains. We spent the second part of the holiday separately. During the war, we traveled along different paths.

An unexpected meeting near Grójec in the house of our younger friend Wojtek Grobicki and the further journey to Warsaw, and then through the destroyed city with traces of recent fights, strengthened our friendship. Fortunately, we found our families complete, the apartments undamaged, not counting the broken windows.

After our return, we met with Dzidek almost every day, discussing the course of the September campaign, anticipating the further course of the war. Our common friend, Staszek Kłopotowski, and his cousin, Zbyszek Madejczyk, who came from Poznań, often participated in these endless discussions.

We also went to the Ujazdowski Hospital, where wounded soldiers were laid. We carried them food, small gifts, and some civilian clothes, if their health condition allowed them to “disappear” from the hospital. Many people, especially young people, did the same. Initially, the Germans were not interested in this activity and there was no reaction from them.

Injured soldiers “revenge” us with rings made of braided horse hair. These rings had the shape of a signet, and the “eye” was made of … toothbrush handles and presented a white eagle on a red field. Wearing such a ring showed that its owner was taking care of wounded soldiers. This kind of proof of commitment was very popular among school and university students. In our environment, such a ring “had to be worn”. However, the situation changed very quickly and the horsehair ring had to be left at home before going out to the street. It could have been the cause of various harassments, and even arrests and sending them to the camp ..

During one of such meetings, one of us remarked: “It’s All All Souls’ Day tomorrow. We absolutely must celebrate those who died in defense of Warsaw. ” But how to do it? There are many graves in the streets, squares and yards. There is no question of placing flowers at all, and how to choose the one that we distinguished. I do not remember which of us said: “it is simple – we will lay flowers on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier!”.

The idea seemed obvious to us. We saw the basic difficulties only in getting the flowers and preparing the ribbon for the bouquets. I made a commitment to buy flowers. I remembered there were many stalls and vendors selling flowers in the Old Town area (I lived in this district).

However, meeting the assumed obligation turned out to be very difficult. All Souls’ Day is just 4 weeks from the capitulation of Warsaw. Literally everything was missing in the city, there were many fresh graves and many people willing to put flowers on them. Moreover, we have very little time left.

I literally trampled the entire Old Town. The case looked hopeless. There were no flowers, not just red and white. Finally, one of the vendors, whom I had already passed several times, seeing my frustration and despairing face, started asking me who these flowers were for. When I answered her, she must have told me three times that it was really for the Unknown Soldier. She went to the next stall, talked to the other stall, and called in two more. There was a fairly lively discussion in which she pointed at me on several occasions. Finally she came back, demanded a word of honor from me that it was for the Unknown Soldier, and said: “Let the bachelor come tomorrow around noon; It’s hard for flowers today, but we will try; it might cost a bit.

Tomorrow – it’s All Souls’ Day. If the promise is not kept, or if I do not have time to get more money, how will I be shown to my colleagues?

The next day, as agreed, red and white carnations wrapped in thick wrapping paper were waiting for me at the stall. When I was taking the hard-earned money out of my pocket, afraid that there would be enough of it, I heard “let the bachelor hide it; we give flowers – the bachelor will lay them. Proud of having obtained beautiful flowers, but also touched by the attitude of the trader, I brought them to an appointment with my friends. We added a white and red – unfortunately quite narrow – ribbon with the hand-made inscription “Heroic defenders of the one who did not die”. In the middle of the sash we placed an eagle embroidered with silver thread on a black background from a cap of an armored weapon (Colonel Wilczewski, Chief of Staff Gen. Thommé – Dzidek’s uncle).

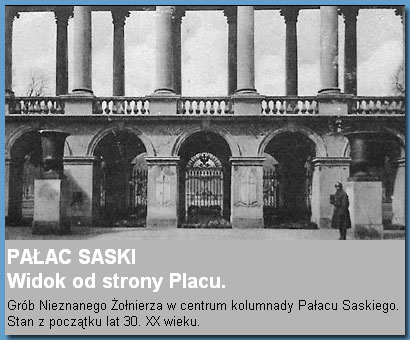

Only after preparing the bouquet did we realize that the basic problems were still ahead of us, and that the intended undertaking belongs to the “crazy” genre. There was no post in front of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, but the Wehrmacht was located in the building of the General Staff adjacent to the Tomb colonnade. Uniformed Germans were entering and exiting the building, who were saluted by the guards standing in front of the entrance.

I do not remember if the Saxon Garden was already intended for “Nur für Deutsche” or if it was closed for another reason. In any case, we had access to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier only from the side of Piłsudski Square. We realized a little late about the “technical” difficulties of our project, but none of us could bring up the proposal to abandon it.

In the afternoon, when it was getting gray, we all four walked up to the colonnade, put a bunch of flowers on it, unrolled a red and white ribbon, stood for a moment and quietly walked away, not disturbed by anyone.

The sentries, standing in front of the entrances to both wings of the building next to the colonnade, were clearly watching us but not reacting. Apparently they had no order.

Zbyszek helped me to clarify the details – years later. He also reminded me that at the end of 1940 he saw our dried-up bunch on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. He recognized her by the sash; dirty, crumpled and very narrow. Probably due to the fact that it was so narrow and inconspicuous, it did not attract the attention of the Germans, as did the little eagle against the black background.

Only me and Zbyszek Madejczyk, out of all four, survived the war. Dzidek Wilczewski was caught in a street round-up and was shot at the end of 1943. Staszek Kłopotowski, arrested after an underground infusion in 1944, died in Gross-Rosen. Zbyszek lost his leg during the Uprising. He died unexpectedly a few days before the publication of this memoir in Życie Warszawy on November 2, 1993. The author of these memoirs was wounded on the last day of the Uprising in Żoliborz.

Warsaw, October 25, 2003 Maciej Bernhardt