Family heirloom – Poland – Remembrance “Occupational colleges”

My memory to the GA.PA National Gallery “Occupation Universities” – including two photographs of handwritten examination certificates for students kept by those teaching the subjects.

The Wawelberg School and the Warsaw University of Technology in 1940 – 1944. Student memories

At the end of the summer of 1940, a friend from the gymnasium named after T. Czackiego and completes – with the news that the car and aviation school, located at the end of Narbutta Street, received permission to start education for candidates who have completed lower secondary school (low matura). It was now called the Technical Vocational School (Technische Fachschule). I went there immediately and barely fit into the limit of places. I found myself in the first grade F. Six parallel classes (from A to F) were launched there in order to provide legal education to as many young people as possible.

It was a very strange school. It was taught by excellent teachers: partly from the aforementioned vocational school, which had an excellent reputation before the war, partly from the Wawelberg and Rotwand school (already before the war, which demanded academic rights). The level of education was high and you could really learn a lot if you had the time and conditions to learn. The more so that the school workshops that survived were perfectly equipped.

We had eight hours of classes six days a week, including a lot of hands-on classes in workshops. The requirements were high, a lot was asked “home”, there were frequent tests and we were often taken to the blackboard. The teaching system was like in secondary schools.

Despite the high level and high requirements, it was difficult to receive an unsatisfactory grade for a period of time. The school ID to some extent protected during less serious round-ups, and quite effectively – against deportation to Germany “for work”. The teachers were aware of this and the great majority of them scared the weak students with an insufficient grade for the period or at the end of the year (which threatened to be forced to go “to work” to Germany), but they did not give such grades.

I owe this school a lot. There, I gained a really solid basics of technology, which was useful to me both during my later studies at the Polytechnic University and in my professional work. Moreover, the school took a lot of time and probably effectively protected against the demoralization of the war. It absorbed us a lot, but we still had time and strength for underground activities and… social life.

For a short period of time, I tried (and my friends) to combine my studies at this school with high school education. We realized very quickly that it was absolutely impossible. Although the scope of mathematics and physics in this school was much wider than in full sets, and in chemistry – comparable, all the humanities, natural sciences and geography subjects were missing. We agreed to keep in touch with the kits to know the scope of the processed material and the necessary information; and that we will pass the high school diploma as extramural students.

My closest colleagues and friends in this period were: Olek Pietrasiński, Andrzej Przyłuski, Andrzej Krupiński, Stanisław Witoszyński, Stanisław Brzosko. I also remember colleagues Witold Grabski, Stanisław Gębalski, Tadeusz Peche, Janusz Luniak, Zbigniew Łukowiecki (I’m not sure if I met him at this school, or later at the PWST, about which I write later), as well as many other faces and figures whose the names, unfortunately, have faded from memory.

In the second year of study at a technical school, classes were held in the old building of the Wawelberg and Rotwand School at Mokotowska Street (between Plac Zbawiciela and Polna).

This change was convenient for me. I was much closer to school, I was wasting less time commuting, and we were now “office” in the city center and it was easier to “jump out” for a while to do something in the city. Science absorbed us even more now than in the previous year. Most of the lecturers were calmly following the pre-war Wawelberg school course, ignoring the fact that the school was two- and not three-year-old and that most of us have a high school diploma, not a high school diploma.

Reflecting today, from the perspective of half a century and the own experience of an academic teacher, I must admit that despite the adversities of the occupation and, for many of us, very difficult living conditions, intensive study effectively protected against war demoralization and gave very good results. Glory to those who organized this school and the underground authorities that they supported all forms of educating young people.

It must also be admitted that the curfew was favored by the progress in science. During the occupation, depending on the situation on the fronts and the moods, the curfew changed from 8 pm to 10 pm. Let us add that during the occupation there were no cinemas, there was no television yet, and having or only listening to a radio was punishable (and not theoretically) with the death penalty.

We appreciated the opportunity to learn, but to some extent we were engaged in learning for lack of other opportunities to spend our time.

I often wonder about the reaction of today’s youth to the demands of the school at that time and to such poor living conditions.

It was certainly very difficult for us, but many of us still had to make some extra money to stay afloat; almost all – as it turned out during the Uprising – were involved in the Home Army, including the very absorbing subversive troops. We also had a personal life. Today I am surprised how it all was possible. However it was!

His education at our school was completed by an enclosed exam lasting two days, transferred “alive” from the customs of the Wawelberg school. Today, this form of examination is almost completely forgotten, so it is worth recalling it.

On the first day, each of the candidates received an examination assignment. As a rule, it was a construction of a device or a special holder needed to process the part, the drawing of which and the data of the machine tools on which the part was to be made, we received along with the sentence (of course, different for each test taker).

The exam lasted 8 hours and all kinds of books, guides, etc. were allowed, except for “neighborhood help”.

One of our professors kindly warned that you can bring the entire library on your back to the cloistered exam, but the topics will be such that you will need to work on them well. In fact, the topics weren’t “malicious” but all labor-intensive.

On the second day, there was an oral exam covering the defense of the project made the previous day, as well as questions about all the material processed at the school. There were three examination groups of 3 to 4 lecturers at the same time. One of the two was defending its project, the third – knowing the results of the project’s defense – asked general questions. If the defense results were good, the questioning committee would give 2 or 3 questions, most often of the type “on intelligence”. If the defense was weak, or the “intelligence” was poor, the mangle would begin. In total, on the second day, the exam for each test taker lasted 30 to 45 minutes.

I passed the final exam without any problems, although after the first day I left school completely exhausted and at home I was not able to even review my notes and repeat – as I had planned – material that could be the subject of questions the next day.

The handing over of the diplomas confirming that we have the right to use the proud title of a machine-building technician took place without great celebrations. The school management came to the conclusion that the quieter and more modest it is, the safer it is for us. We were even forbidden for our parents, our girlfriends, friends, etc. to come. The less people there are, the better.

There were no speeches, thanks, etc. The headmaster was reading the names one by one, handing out the diploma (written in Polish and German), donating a paw, and one of the professors standing next to him discreetly advised (but it was an offer that he could not refuse) to leave the school one by one and do not gather near it.

I was one of the first to receive my diploma. That’s the benefit of a surname starting with B. I went out with a few colleagues from the top of the list. We stepped into a tiny shop that was located almost directly across from the school. It was theoretically a grocery store, but as it was during the occupation, it offered many different goods after acquaintances, which did not always correspond to its name. We knew this shop well, because many of us bought their modest lunch and even lunches there, as well as notebooks, drawing paper, pencils, ink and similar “groceries”.

Of course, for good friends there was also home brew, of a good quality. We celebrated our diplomas with a glass of moonshine, bitten them with cucumbers or tomatoes. When I was leaving, I was approached by my friends whose names began with the letters D, E, F; when I was leaving for the second time – my friends were just entering G, H, I, J. This happened several more times.

My head was buzzing when I met Staszek Witoszyński, who was just leaving school. I couldn’t help but drink with him. At this point, however, the film broke off exactly. My friends put me in a cab and drove me home to Miodowa.

Shortly after that, I fell ill with infectious jaundice. I was in town on conspiracy issues. I was walking home and feeling very tired. I was wondering that I would have to take a little vacation, because very intensive studies, conspiratorial classes, and not the best nutrition, apparently exhausted me excessively.

I perfectly remember that on the corner of Trębacka and Foche’a Streets (now Moliera) – I suddenly felt faint. I felt that I had a high fever. I was not far from my home, less than half a kilometer. I came with great difficulty, making many stops along the way.

I was really really sick. I lay in bed for over two weeks, and then slowly recovered. I was very weak for a long time, and the necessity to follow a strict diet – it was only a problem during the occupation – was not conducive to regaining my strength.

During my convalescence, I learned from my colleagues that in the fall of 1942, the University of Technology was opening in Warsaw. The Germans agreed to launch the State University of Technology (PWST) with Polish as the language of instruction. It was supposed to be a two-year semi-high school. Its graduates, in accordance with the assumptions that decided to launch, were to be used by the Germans to develop Siberia after the victorious end of the war. There were supposed to be faculties: mechanical, electrical and construction (I don’t remember if also chemical). Classes were to be held in the premises of the Warsaw University of Technology, whose main building, destroyed in 1939, was rebuilt for this purpose. The teaching staff were to be academic teachers from the Warsaw University of Technology and from the Lviv and Gdańsk Polytechnics present in Warsaw.

The Polish underground authorities, with which the professors’ staff had close contacts, had no objections to the launch of the university and the teaching of Polish youth there. On the contrary, it was believed that all possibilities of science and the incoherent German policy in this regard should be used.

German political authorities believed that Poles would be satisfied with a 4 or 5-grade primary school, and any other education was harmful and dangerous; while the economic authorities were getting ready to develop the acquired (and to be conquered) areas and were aware of the shortage of technical staff, especially those that could be used in areas not attractive to German cadres.

The basis for admission to the PWST was to pass a competitive exam. I was seriously afraid of him, because the disease made it impossible for me not only to thoroughly prepare, but even to repeat the material in a cursory manner. In addition, the exam date was just around the corner, and I was still in a very bad shape, even reading fiction books.

My examination papers were submitted by my colleagues. But until the end I was not sure if I would be able to take the exam. On the eve, my father (doctor) examined me thoroughly. He wasn’t entirely sure if I should take this exam. But he had prepared some medicine for me to take if I felt faint. I had them in a flat bottle, diluted with water so that half of the contents corresponded to one required dose. So I had two doses that I was allowed to take not less than an hour apart.

On the day of the exam, my mother took me to the Polytechnic in a carriage. My closest colleagues, who were all also taking the exams at the PWST, knew well about my illness and the present problems associated with it. The others looked at me as if I was a freak. For some time, after I started my studies, I was said to be “the one that my mum brought him to the exam”.

The entrance examination was in mathematics and physics. The math problems were fairly easy. In any case, after our technical school, they did not give me any difficulties and I solved them fairly quickly. But I knew that I had a “talent” for making silly mistakes in a hurry and that the whole thing had to be carefully checked. At the same time, I felt extremely tired. Suddenly I stopped understanding what I wrote a few minutes ago. Until now, I must have been “held by my nerves.” So I stared out the window for a long moment to relax, then reached in my pocket for the bottle, opened it, and took a long sip of the potion. At that moment, I met the gaze of Professor Pogorzelski who was watching us (a famous mathematician, professor of the Warsaw University of Technology before -, during and after the war). He looked so amusingly surprised that I could hardly contain myself laughing.

I waited a moment for the medicine to take effect, checked the assignment, corrected the minor errors I had found and returned the work to the professor. When donating, I tried to explain to him that I had to take the medicine, but he didn’t really want to listen to me.

I met professor Pogorzelski after the war; I took “Mathematics III” with him (he passed the first two on the basis of my exams at PWST). After receiving the student’s book with the exam result entered, I reminded him of our meeting at the entrance exam to the PWST. He remembered them perfectly. He admitted that at first he thought I was taking a squeegee out of my pocket. later he was convinced that I was sipping alcohol from the bottle. “You know, in those days I have learned not to be surprised.”

He asked me for the index again, looked at the fresh entry and said: I wish you had reminded me of this history before I entered it; I’d bet you five, and so you’ve got four and a half. I wrote it so that I have no way to correct it.

I don’t remember if the physics exam was the same day or the next day. But I remember that it included as many as 10 simple tasks. I did well 9. One was about acoustics and none of the candidates who had graduated from technical schools solved it. This department of physics was not taught at our place. On the other hand, those who took the final exams in complete sets had no problems here.

As far as I remember, classes at the PWST started in September, and not in October, as was the custom of universities. We had a huge learning load: we had 8 hours a day five days a week, and 6 hours a day on Saturdays. At the same time, most professors did not include in their lectures that, in accordance with the intentions of the German authorities, it was to be a semi-high school. They gave lectures in the same way as before the war at the Polytechnic.

The pace of learning was enormous. During the first year, we completed almost the full course of the first two years according to the pre-war program. We were only “given” technical drafting and general machinery, which most of us already knew from technical schools. However, the few students who had not been to this type of school before had additional great difficulties with precisely these subjects.

The “squeezing” of the material caused the temporal correlation of the objects to partially cease to exist. For example, in his lectures on physics, prof. Wolfke used the differential and integral equations that prof. Pogorzelski. The assistants during exercises and colloquiums did not bother with such trifles either.

Today, a similar situation would cause student protests, press publications, and perhaps even lead to a strike. Then it encouraged us to learn and caused spontaneously groups of learning together and overcoming the difficulties encountered. It was a tough school.

The lectures were conducted by such famous pre-war professors as: Pogorzelski – mathematics, Huber – theoretical and technical mechanics, Wolfke – physics, Wesołowski – metallurgy, Stefanowski – thermodynamics, Biernacki – metalworking, Moszyński – machine parts ..

The PWST (State Higher Technical School) card effectively protected against deportation to Germany for work and with less serious round-ups. In other cases, it was practically irrelevant.

In the first months of classes, one day the German police surrounded the entire area of the Polytechnic. It looked very serious, especially since we already knew the history of the professors of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków being deported to concentration camps. This time it all ended happily, but it wasn’t that much that could have been much worse.

On the campus. two Polish anti-aircraft guns, a remnant from 1939, stood near the building of physics. No wheels, no locks or sights. But all the other mechanisms were working fine. By turning the appropriate cranks, it was possible to direct the barrel of the gun in all possible directions. In the breaks between classes, the old bulls had nothing better to do, just played with cranks and “waving” gun barrels. Someone took a photo as a souvenir and gave the film to be developed for the photo shop. There, German spies spotted him immediately and reported to the Gestapo that military training was taking place at the PWST.

Apparently, it was close to closing the school. Fortunately, its German director, prof. Güttinger was able to explain the whole matter to the police and everything ended with a lot of laughter (at the Germans) and a lot of drunkenness.

For us, it was one more warning that the presence of spikes should always be reckoned with. We’ve known about it for a long time, but still underestimated the threat.

Prof. Güttinger was seconded from one of the most famous German polytechnics (unfortunately I don’t remember which one). During the First World War, he lost both legs on the Western Front and won an iron cross. Until his arrival in Warsaw, he lost two sons in the Second World War.

He turned out to be a very decent man. During the Warsaw Uprising, he was allowed to leave the Polytechnic area occupied by the Home Army troops, where he was caught by the outbreak of fighting. A short-term cessation of fire was agreed to allow Prof. Güttinger across the front line.

After the war, one of the first resolutions of the polytechnic senate expressed recognition for his attitude during the war.

Students practically did not come into contact with Güttinger. I don’t know if I have seen him briefly 3 or 4 times during the two years of my studies. He had a typical form of a Prussian officer, a dry face, his hair was cut short, and he looked definitely unpleasant.

I remember the incident that made all of us furious at first; only later did we (and not all of us) understand its true meaning.

At the beginning of the last hour of class, one of the professors came to the Physics Auditorium, where we were listening to Professor Wolfke’s lecture, and informed us that, on Guettinger’s order, we were all punished to stay in “class detention” for four hours. It was due to some mess in the toilets, flooding of something with water and something else.

We were outraged. How could we treat us grown-ups like puppies from elementary school? In addition, such nonsense commands are given to us by the professor! Of course, some of us didn’t listen and left the audience. It turned out, however, that all exits from the building were closed.

After an hour or a half, we were announced an “amnesty” and the door was opened. In the city, we found out that there was a large round-up in the city center at the time when we were sitting in the “goat”.

There were more similar stories, although not so spectacular. Unfortunately, I don’t remember the details anymore. I also know that prof. Guettinger intervened (though I don’t know with what effect) in the arrests of some professors and students.

Prof. Güttinger had a very strong professional position, and as a knight of the iron cross he could afford a lot. He was not the only German in the leadership of the university. There was also his deputy – unfortunately I do not remember his name anymore – who we knew was an extraordinary scandal and a high cone in the Nazi hierarchy. I’m not sure about it, but I think he was shot during the Uprising.

PWST exams

The program of studies at PWST was not (probably on purpose) specified, and the professors taught a normal course at the Polytechnic, so there were basically no clear examination criteria.

Most of the professors solved it as follows: If you had passed the exercises and at least a green idea about the subject, you would get a satisfactory grade. It made it possible to keep the school ID.

If the test taker showed good knowledge of the subject, he would usually learn (although in a very different form) that he was well prepared and therefore would receive the same question that was asked at the Polytechnic before the war. Just out of curiosity and for fun. In the case of a positive answer, more questions appeared most often, and the professor, apart from the grade on the examination list, wrote down something else in his notebook. Almost all of these notes survived and after the war, individual items were scored without any reservations after the war. In my index, half of the exams (almost all from the first two years and some from the third year) are passed on the basis of the occupation records of the lucky survivors at individual professors.

Some have tried to take advantage of the opportunity to score more than their due.

One of my colleagues – let’s call him Mr. “G” – received a certificate in June 1944 that he had listened to all the lectures and passed all the exams provided for by the PWST program and that he had to complete his diploma thesis. Such certificates were issued to all who met the required rigors. The school was supposed to be a two-year school, we had just finished our second year of education and it was not very clear what to do next, especially as the front was not too far from Warsaw. Theoretically, we were supposed to do something like a diploma thesis in the fall, but no one took it seriously, because it felt that the war was finally ending.

Mr. “G” left for his family, somewhere east of Warsaw, and in September 1944 in the liberated Lublin, where he presented his certificate from the PWST, signed with the name of a well-known professor at the Warsaw University of Technology. There he found a professor at the Lviv Polytechnic, who gave him the subject of his diploma thesis. He prepared the work in no time, but could not defend it in Lublin for formal reasons. So he submitted it to the defense in the spring of 1945 at the Lodz University of Technology (Warsaw was not yet operational). Lodz was the seat of, inter alia, prof. Moszyński from Warsaw. he reached into his notebook and said: none of that; Mr. “G” completed projects in machine parts in the scope required at the PWST, and two more (or maybe even three) more to be included in the curriculum of the University of Technology, and also a few more subjects from the third and fourth year of studies,

During the first year of PWST, attendance at all classes was carefully monitored. In the second year, the situation changed radically. Formally, attendance was checked as before, but the lecturers were not surprised that almost everyone was present when reading the list, and the lecture room was sometimes half empty.

If someone was absent from the class, it means that he or she had other more important matters and no efforts were made to pursue the truth too rigorously. Every medical certificate was good, and the train delay certificate was the best. In this period, trains were regularly late.

We had access to original prints (it was not a problem; most of the employees were Poles). The stamps were also original or made with the use of a child’s printer. Our faculty have become programmatically gullible and “believed” in the most unbelievable nonsense. It also happened that they quietly suggested to the students to come up with something better, if possible.

It should be emphasized that we did not use these opportunities to break away from classes to a greater extent than required by the underground and really very important matters of everyday life (and maybe sometimes a pretty girl as well). I think that the conscientious treatment of science was influenced by the fact that we were well aware of the fact that we had gained a unique, in the scale of the country, chance for legal education, under the supervision of the best Polish professors. Our underground superiors also appreciated this opportunity. We were absolutely forbidden to bring weapons, blotting paper and the like forbidden things to the campus. We had a duty to be absolutely “clean” (At the same time, however, as we learned many years after the war, the laboratories of the University of Technology were used, to carry out technical analyzes of new weapons and German military equipment. Some professors, e.g. prof. Groszkowski, who analyzed the remains of the V-2 rocket many months earlier than the world learned about its existence. The approach of the underground authorities to our science is demonstrated, among others, by adjusting the dates of some trainings and collections to… classes at the PWST. This does not mean that the school had priority over the conspiracy. However, in those cases, when it was possible, we tried not to disturb our learning. which analyzed the remains of the V-2 rocket months earlier than the world learned of its existence. The approach of the underground authorities to our science is demonstrated, among others, by adjusting the dates of some trainings and collections to… classes at the PWST. This does not mean that the school had priority over the conspiracy. However, in those cases, when it was possible, we tried not to disturb our learning. which analyzed the remains of the V-2 rocket months earlier than the world learned of its existence. The approach of the underground authorities to our science is demonstrated, among others, by adjusting the dates of some trainings and collections to… classes at the PWST. This does not mean that the school had priority over the conspiracy. However, in those cases, when it was possible, we tried not to disturb our learning.

It should be added here, however, that as the front approached Warsaw, that is, from the spring of 1994, the understanding of our underground superiors decisively decreased; also we were less and less involved in the school rigors.

The colleagues from my studies mentioned in these memoirs, and at the same time friends, were also my comrades-in-arms in the underground and we served in one team and section in the Warsaw Uprising.

At dawn on the 2nd Soerpnia, during the transition from Żoliborz to the Kampinos Forest of the “Serb” battalion (later renamed “Zubr”) of the “Żywiciel” District, more than 70 soldiers of the 2nd company of Lieutenant Starża were killed; among others, my closest friends, colleagues and comrades-in-arms from one section:

Andrzej Krupiński “Jacek” – the body was not found,

Waldemar Misiorowski “Papawer” – buried at the military cemetery in Powązki,

Zbigniew Przestępski “Gozdawa” – buried at the military cemetery in Powązki,

Jerzy Miller “Mak” – buried in the cemetery in Wawrzyszewo in the insurgent headquarters.

Maciej Bernhardt – during the occupation – student of the Wawelberg School and the Warsaw University of Technology; currently retired professor of the Warsaw University of Technology.

(Historical Journals of Paris Culture No. 118; 1996; pp. 95-108)

(excerpts from MEMORIES FROM THE PRE-WAR, WAR AND THE FIRST POST-WAR YEARS)

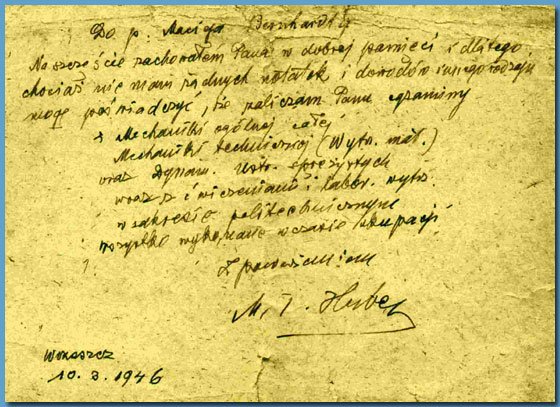

Content from photos:

The text is not legible, so I present their content below:

A. To Mr. Maciej Bernhardt

Fortunately, I kept you in a good memory, and for this reason, although I do not have any notes or other types of evidence, I can certify that I have passed your exams.

from general

mechanics, technical mechanics (material strength) [strength of materials] [wytrzymałość materiałów]

and vibrations elastic [regimes] [ustrojów]

with exercises and the fitness laboratory. [endurance] [wytrzymałości]

everything was done during the occupation.

Sincerely, MT Huber

Wrzeszcz

10.2. 1946

_______________________________________

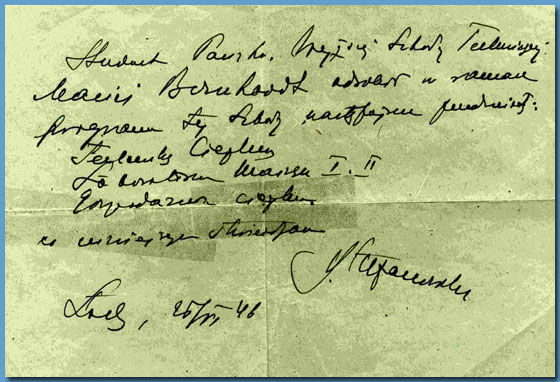

Student of States. Of the University of Technology Maciej Bernhardt did the following subjects as part of the program of this school:

Thermal engineering ,

Laboratory of Machines I and II

Heat management

which I hereby certify

B. Stefanowski